The Black Panthers Movie`s Luster and Tarnish

advertisement

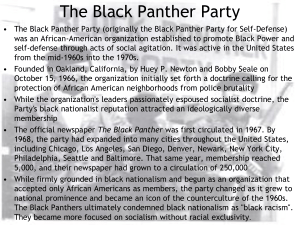

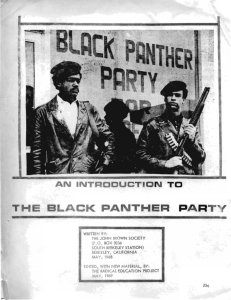

The Black Panthers Movie’s Luster and Tarnish A new movie on The Black Panther Party for Self Defense, The Black Panthers, has planned showings in 31 cities nationwide this summer and fall, after playing at 34 film festivals previously. The film does a good job at showing the positive community organizing done by the radical leftist group in the 1960s. The film also presents many great interviews and much good archival footage. The film only strays into negative historical revisionism in offering an overly negative presentation regarding two of the top three national Black Panther leaders. “Vanguards of the Revolution” Baltimore’s Morgan State University Professor Stanley Nelson listed the subtitle of his movie as, “Vanguards of the Revolution,” harking back to the language used at that time. These words could be taken as either the overly optimistic voice of some radical activists, or the propaganda used by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) whom Nelson quotes in the film. The Black Panthers quotes J. Edgar Hoover’s famous line about The Black Panthers being the number one threat to national security (A movie theater’s staff thought their safety was threatened during a Saturday Baltimore screening when someone tweeted they would shoot people, and the staff all left the theater, canceling the two remaining shows where Nelson planned to speak). The Black Panthers begins by showing how the organization started as a civil rights political party opposing police brutality and setting up many “survival programs.” These programs included free breakfast for poor children, free medical clinics, and housing organizing groups. It also included political education programs, particularly through its national newspaper. The film rightfully displays how their great community organizing made them role models for other radical ethnic groups. A better film on The Black Panthers, former Panther Lee Lew Lee’s All Power to the People!, explicitly says how groups such as the Puerto Rican, Young Lords, the American Indian Movement and the Asian, Yellow Peril, all learned from and modeled themselves after The Panthers. The film also shows at least several great speeches by some Black Panther leaders. It includes particularly good speeches by 20 year-old Chicago Panther leader Fred Hampton as well as snippets of speeches by national Panther cofounder, Bobby Seale. Hampton speaks his famous lines, “You can kill a revolutionary, but you can’t kill the revolution.” Stanly Nelson presents National Black Panther Secretary of Communications Kathleen Cleaver a few times, and includes short but good interviews of her. The movie then begins to detail the attacks on The Black Panthers, starting with the police shootout with Huey Newton. It’s at this point in the movie that Nelson appears to leave out some context for why Newton was stopped by police, where he and a police officer were both shot. Nelson failed to mention what has been noted in at least several books about the Panthers, which is that the police officers had a list of Black Panther license plates on them that they arguably intended to target. Highlighting the FBI’s War on the Panthers The Black Panthers does do a relatively good job of showing several other key instances of the FBI’s Counterintelligence Program targeting of the Panthers. It presents good details on the targeting of the New York Black Panther leadership, which came to be known as the New York 21. It only leaves out some of the top names, such as Lumumba Shakur, who headed New York’s largest chapter in Harlem, as well as leaving out Afeni Shakur (Tupac’s mother) and not mentioning Assata Shakur, nor Bronx Panther leaders Sekou Odinga and Zayd Shakur. Maybe many names were omitted to cut down the length of the film or maybe the Ford Foundation’s co-funding of the film led to such omissions. Director Stanley Nelson mentions some of the FBI’s Counterintelligence Program (Cointelpro) tactics, but fails to mention them with the splitting of Huey Newton’s Oakland national Panther office and the New York chapter. For example, top Panther historians Ward Churchill and Jim Vander Wall’s two books, Agents of Repression and The COINTELPRO Papers, discusses the fake letters and undercover agents that helped accomplish this split more specifically. The director does give good details about the New York trial of the Panthers being the longest of its time (over two years) and the jury’s acquittal of all the New York defendants in 2-3 hours. Nelson also gives some specific details about the targeting of the Chicago Black Panthers that included the tragic murder of Fred Hampton in his bed. It further shows excellent footage of the FBI targeting of the Los Angeles Black Panther office four days later. One Los Angeles Panther who fired back at a police fuselage of bullets in the early morning attack made a very evocative statement. He said that he’s “never felt so free as I did in the middle of that firefight.” Again, omissions are far from a major issue when a film needs to be a reasonable length, but they do bear pointing out. Nelson’s film fails to mention the murders of the original LA Panther leaders, Jon Huggins and Alprentice “Bunchy” Carter. It also fails to mention the false imprisonment of Los Angeles Panther leader Geronimo Pratt a year or two after a sniper’s particular targeting of him during that attack on his Panther office. Incorrect Shaming of Top Panther Leaders? A much more problematic aspect of Stanley Nelson’s The Black Panthers comes in the way it portrays two of the top three national Black Panther leaders, without the full context of their targeting. The film contradicts the accounts of welldocumented books on Eldridge Cleaver. It quotes people calling him “crazy” early on, when he was made the Panthers national Minister of Information. It also doesn’t relate the details of the 1968 police attempt to murder Cleaver. After several negative comments about Cleaver, Nelson depicts Cleaver as enlisting young Panther Bobby Hutton in joining him to attack police. This account appears spliced together from interviews with Panthers and taken out of context. Many books covering this incident, such as The COINTELPRO Papers, detailed how the Oakland Police “Panther Squad” deliberately provoked this attack on Cleaver and Hutton. Another book, Bitter Grain, stated that Cleaver and fellow Panthers put the word out that Oakland activists shouldn’t riot as police would use it as an excuse to kill Panther leaders. Interviews of former military snipers by historians such as attorney William Pepper confirm this belief. Despite having one of the highest per capita black populations, Oakland was one of the only major cities that didn’t riot after King’s assassination. Police then used a made-up excuse to attack Cleaver and Hutton. Nelson’s movie appears to blame Cleaver for Hutton’s murder at the hands of police. The Black Panthers rightfully discusses some Cointelpro tactics around the time it discusses the split between Panther national cofounder, Huey Newton, and Cleaver. Yet, it somehow does not describe exactly how these tactics were used in this split, only seeming to blame Newton and Cleaver’s less rational impulsiveness. This split also set Newton against the imprisoned New York Panther leadership, yet the film appears to present the division as a natural disagreement, rather than showing it within the context of Cointelpro tactics being used. Churchill and Vander Wall’s books, along with the film, All Power to the People!, the feature presentation of the first Black Panther Film Festival, detailed the U.S. intelligence-written letters and undercover agents used to create these divisions. Too Much Testimony from a Likely Undercover Agent? These sources, The COINTELPRO Papers and Agents of Repression present many Panther reports that one particular Oakland Panther, Elaine Brown, was actually a U.S. intelligence undercover agent. All Power to the People! contains copious details and statements from respected Black Panthers regarding Elaine Brown’s history and work for U.S. Intelligence, as guided by her self-reported, lifetime “mentor” Jay Richard Kennedy. David Garrow’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book on Martin Luther King, Bearing the Cross, details how Jay Kennedy was the CIA’s top spy in the Civil Rights movement. MLK’s friend and historian, William Pepper, also notes Jay Kennedy’s top spy work. All Power to the People! shows Bobby Seale stating that many Panthers told him of Brown’s spy work and influence over Huey Newton to expel other Panther leaders and take apart the organization. Most importantly, when Elaine Brown threatened to split the black vote within the Green Party that was looking to run Congresswoman Cynthia McKinney for president, McKinney backers Kathleen Cleaver and Geronimo Pratt (changed to Geronimo Ji Jaga by this time) took action. The two Panther leaders put out a letter from Geronimo detailing Elaine Brown’s history of reported psychiatric hospitalization, infiltration of the Panthers, and aiding of U.S. intelligence in the murders of LA Panther leaders Carter and Huggins. Furthermore, Geronimo detailed how Newton told him that Elaine Brown developed way too much influence over him by regularly bringing beautiful women and cocaine to him just after Newton got out of jail in 1970. Newton eventually got out from under her influence and found that Brown had played a part in helping frame Geronimo Pratt on a murder charge. Several decades later, after Geronimo and Cleaver sent this letter out to activists, Elaine Brown sued them for slander and defamation of character. This writer and many other activists sent Cleaver documents to back her and Geronimo’s claims and the suit was dismissed. Elaine Brown was one of many undercover agents used to manipulate Huey Newton. Two other confirmed undercover agents surrounding Newton included Richard Aoki and Earl Anthony. Anthony admitted his agent status in his book, Spitting in the Wind. In All Power to the People! New Haven Panther George Edwards quotes CIA whistleblower John Stockwell saying that from 1971 onwards the CIA waged psychological warfare on Newton. Stanley Nelson did a huge disservice to Newton’s legacy in only showing Newton’s negative actions, instead of the mass of evidence backing up the psychological warfare being perpetrated on him. Nelson then repeats the police-proposed myth that Newton died in a random drug deal. Various writers, including Churchill and Vander Wall, have presented eyewitness reports, along with police and FBI foul play around Newton’s murder, that support how U.S. Intelligence assassinated Huey Newton in 1989. That decade, Newton received his PhD, started a Panther school, was working to free Geronimo Pratt, and had just contacted an active New York Black Panther about reconvening the organization. Evidence supports that many Black Panther leaders experienced lesser but similar psychological warfare for years to come. Stanley Nelson’s film, The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution, brings more awareness to many great aspects of this legendary, armed community organizing group. While it also provides a balanced perspective on The Black Panthers, it’s too bad that the overly negative portrayal of two top Panther leaders might tarnish some of the movie’s positive messages in excluding more context of U.S. intelligence’s influence. John Potash is the author of, The FBI War on Tupac Shakur and Black Leaders, and the newly released, Drugs as Weapons Against Us.