This paper investigates the ways in which urban development

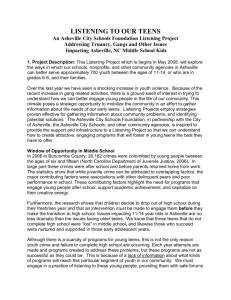

advertisement