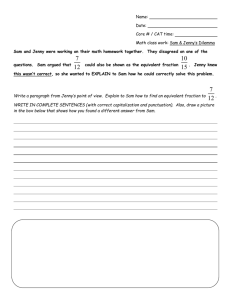

Arkady Gaidar

advertisement