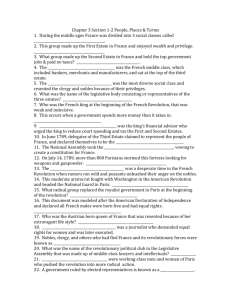

The estates

advertisement

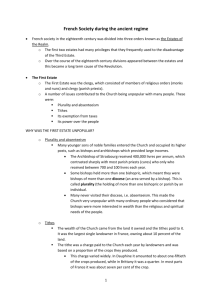

11 Ge bi (Fb) Origins of the French Revolution From: Sally Waller: France in Revolution 1776-1830, pp.5-10. 1 The estates France was a large country and, by the 1780s, had a population of not quite 27 million. Under the ancient regime, the French people were divided, according to their status, into ‘estates’ or social groups. These groups were quite unequal in size and in power. It is difficult to give exact figures for this period, but it has been estimated that the First Estate, the clergy, had around 170,000 members, the Second Estate, the Nobility, had 300,000 – 400,000 members, while the Third Estate, the commoners (or everyone else), made up the rest of the population. Although the types of people within each state varied considerably, each of these groups had a separate function. The First Estate The clergy, clearly defined by its distinctive clothes and spiritual duties, occupied the highest position in society and its members were known collectively as the First Estate. These members, however, varied tremendously in type. There was a huge difference, in terms of wealth and power, between the humble parish priests, monks and nuns, the bishops, archbishops and cardinals, who came from the ranks of the nobility. Although, as a whole, the Church was wealthy, deriving an income from the rents and dues attached to the church land1 that it owned, as well as the tithes2 that everyone was obliged to pay to the Church, not all the members of the Church were rich. Indeed, many parish priests were far poorer than their parishioners.3 Nevertheless, under the ancient regime, clerics were very influential in France. Although religious observance varied enormously between areas, the Catholic Church governed the daily lives of most of the men and women of France. Its spiritual role was regarded as essential to the well-being of the nation, and the Church controlled education and provided for the care of the sick. In return for their contribution to society, the clergy of the First Estate shared a number of privileges. They could, for example, only be prosecuted in their own church courts. They could not be asked to perform military service or billet4 (house) troops, or provide money for the support of royal troops. They also had various financial privileges and were not required to pay the taille (the main French direct tax). Instead, the clergy had the right to hold their assemblies, at which they could make decisions about their own affairs and offer grants, known as dons gratuits, to the king. The Second Estate The Second Estate was made up of the nobility, which owned around a fifth of the land of France. Like the clergy, the nobility was also divided, and not all were exceptionally wealthy. The first group was the ancient nobility, including members of the king’s own family, whose status came from their birth. They were known as the nobility of the sword, as they were originally the only men allowed to wear a sword. In some areas, however, where families had fallen on hard times, it was status rather than wealth that marked them out from their fellow Frenchmen. The other group was made up of those whose noble 1 The Church owned c. 15% of the land of the kingdom overall, however, ist landed influence varied from 5% in parts of the west to 20% in parts of the north and the east. 2 A payment amounting to a tenth of a person’s income. These were originally payable to the church in the form of produce. 3 Gemeindemitglied 4 unterbringen 11 Ge bi (Fb) Origins of the French Revolution From: Sally Waller: France in Revolution 1776-1830, pp.5-10. 2 status derived from their work they did and was known as the nobility of the robe. Nobility might be acquired through the performance of a particular job, such as a judge, given in return for money, as a reward for outstanding military service or, more often, as a ‘perk’5 accompanying a particular governmental office. Venal6 offices were those that could be purchased and proved a useful source of income for the crown during the eighteenth century. Consequently, the numbers of the Second Estate had grown quite considerably during the course of the century. What the nobility had in common was a shared attitude to work and common privileges. ‘Living nobly’ generally meant living off the rents of landed estates7 (unearned income) and the attitude still persisted, particularly among the nobility of the sword, that a military career was the only suitable profession for a nobleman’s son. When a man entered the ranks of nobility, he normally abandoned business and trade although, by the end of the eighteenth century, there was a small group of ‘business nobility’ in France. Noblemen shared honorific privileges, such as the right to wear a sword, display a coat of arms or take precedence at public ceremonies, which helped reinforce their belief in a natural superiority. They also held a privileged position in law and had a right to be heard in a high court of law and to be beheaded rather than hanged if found guilty of a capital offence. They were exempt8 from the corvée royale (forced labour on the roads) and, perhaps most importantly, were exempt from the taille (the oldest form of direct taxation) and gabelle (salt tax) and had a lower rate of assessment in other direct taxes. The Third Estate The Third Estate was a very mixed group of those who were neither clerics nor nobility. By far the greatest proportion of this estate, comprising between 80 and 90 per cent of the population as a whole, was peasantry. The remainder was made up of the bourgeoisie and the urban workers. The bourgeoisie (middle classes) is a rather vague term, which is often divided in turn into the haute bourgeoisie, such as the wealthy merchants and tradesmen, and petite bourgeoisie, such as small shopkeepers and craftsmen. The Third Estate also included those who were little more than beggars and lived on the borders of society. Peasants worked on the land. By far the greatest number worked as labourers on the land of others but there were some better-off peasants who had managed to acquire land in their own right. Most peasant holdings were small but, collectively, the peasantry owned around a quarter of the land of France. Once again, this group was very varied. At the top were the richer, land-owning peasantry and the tenant (renting) farmers of large estates and, at the bottom, the journaliers (day labourers) who could never be sure where the next day’s work would come from. The bourgeoisie relied on skill, rather than physical labour, for their income. They included professionals such as doctors, lawyers, non-noble office holders, financiers, traders, teachers, artists and master craftsmen. They were a mixed band, although they shared some education and ‘relative’ wealth. Their numbers had expanded during the eighteenth century, roughly trebling9 during the period 1660-1789, through the growth of commerce 5 Vergünstigung; Sonderzulage käuflich 7 The land held by the Second Estate was unequally dispersed, with 40% in parts of the south-west, 33% in Burgundy and less than 10% in Flanders. 8 ausgenommen; befreit 9 verdreifachen 6 11 Ge bi (Fb) Origins of the French Revolution From: Sally Waller: France in Revolution 1776-1830, pp.5-10. 3 and overseas trade. At the top, the leading bourgeoisie identified more closely with the Second Estate, which many tried to join through the purchase of office, than with the peasantry, and they invested any surplus wealth in land and property. The lower bourgeoisie had fewer opportunities for advancement. The urban workers who lived in large towns were made up of small shopkeepers and skilled (artisan) or unskilled (manual) workers. Few members of the Third Estate had privileges. They were required to pay direct taxes such as the taille and capitation, and indirect taxes, such as the gabelle (salt tax), the aides on drink, and taxes on tobacco, as well as their tithe10 to the church. The Third Estate was also required to do unpaid labour service to maintain the king’s roads, a duty known as the corvée royale, although, in practice, wealthier citizens could buy their way out of this obligation. Peasants also had considerable feudal duties and were required to make money payments or provide labour for their masters. In parts of France, they were also obliged to use their lord’s mill, oven and winepress, for which they paid a fee, but there was a good deal of regional variation. Nevertheless, there is no denying that the demands, particularly for the peasantry, were heavy overall. 10 A payment amounting to a tenth of a person’s income. These were originally payable to the church in the form of produce.