study of australia`s approach to aid in indonesia

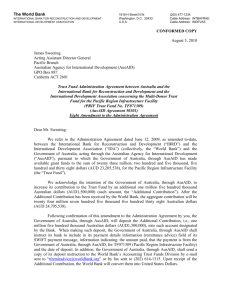

advertisement