Sara`s Thesis - condensed

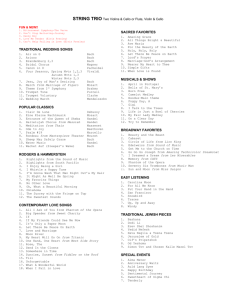

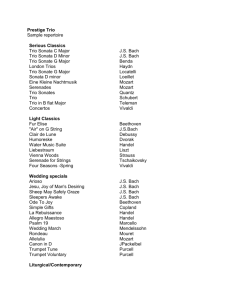

advertisement