Hamlet – study notes

advertisement

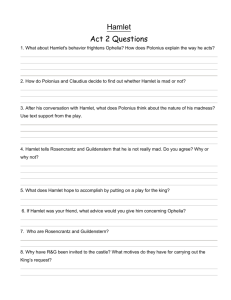

Hamlet – study notes, part 1 Katherine Parrish, 2004 Hamlet is a complicated and complex play. To be completely truthful with you, I’ve never understood its popularity- it’s long, there are vast scenes, whole Acts, really, where people do nothing but talk, the most entertaining aspects of it are found in word play, which might appeal to a few geeky English teachers, but is hardly the cup of tea of the general public, and Hamlet is a self-obsessed, moody, irrational prig. So why bother studying it? Well, part of it goes towards making sure you’re “educated” folks. It is certainly the most renown of Shakespeare’s works, and the play itself has had more influence on the English language than any other single work besides the King James Bible. Part of the reason for this is that it actually contains more invented words and more single use words than any other of Shakespeare’s plays. ( And this gives us some clue as to its appeal- Obviously, Shakespeare was excited about this work, he obviously thought he was doing a new thing. New thoughts had to be thunk- and these thoughts required new words. What was so new? It could be argued that in Hamlet we see the full expression of the birth of the western liberal human subject- the individual whose internal being is a whole universe unto itself, who has to determine his role in the universe through reason, not through faith, and who feels a sense of accountability not to God, to the Church, to the State, or even to fate, though there is some discussion of this in the play, but ultimately the liberal human subject is subject to himself and himself alone. His (and I use this pronoun intentionally) ultimate goal is self-determination- it’s the first full, loud cry of “I just gotta be me!,” the cry that, generations later, will give birth to the America we know today. Though this attitude might be familiar to us, it was still a new concept for Hamlet’s audience. We can see this reflected when we compare Macbeth to Hamlet. Macbeth constantly invokes the great chain of being- Macbeth and Lady Macbeth’s crime is that of self-determination. Hamlet, whose action in the end is the same as Macbeth’s, is clearly praised for the actions that damned the power-hungry couple. The opening up of the freedom, the loosening of the old structures of society- fate, God, myth- can be seen in the structure of play itself. It does seem that every man is for himself in Hamlet- people appear and disappear and we never see them again- Reynaldo, Osric, even the Players, all seem to pass through the play without any sense of coherence. We do not miss them when they are gone. And yet the play is not disordered, or completely let loose. Once Hamlet enters the play, we are hardly left out of his sight for an instance. If indeed man is now the center of all things, Hamlet is clearly that center. And this is a crucial point. For though the play is not disordered, the world it describes truly is. We see this from the very opening lines. Francisco is the guard on duty, and yet it is Bernardo who asks “who goes there” when he comes to relieve him. Francisco immediately corrects him, but it is an indication that all is not well, that the time is “out of joint.” The ghost that appears is clearly another indication. Horatio charges it with “usurping” the time of night; in fact, Old Hamlet is the one that has been usurped of “life, of crown, and of 106748048 Page 1 of 5 queen.” The ghost is again described as being “extravagant”, literally “out of bounds” (1.1.140). Claudius is anxious to put down the rumours that the state is “disjoint and out of frame,” though at the time, only he knows the true reason (Act 1.2) And for Hamlet, the news that a Ghost has been walking abroad is only a confirmation of his deeper suspicions that “all is not well (1.2.). As for Neo in the Matrix, it takes a voice from beyond the material world to expose the cracks in that world, to “hold the mirror up to nature” and put her virtue to scorn. The Second Coming W.B. Yeats Turning and turning in the widening gyre The falcon cannot hear the falconer; Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned; The best lack all conviction, while the worst Are full of passionate intensity. Surely some revelation is at hand; Surely the Second Coming is at hand. The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert A shape with lion body and the head of a man, A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun, Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds. The darkness drops again; but now I know That twenty centuries of stony sleep Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle, And what rough beast, its hour come round at last, Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born? I have said the profound sense of betrayal Hamlet feels is dealt him by his mother, coupled with the loss of his father is metaphorically linked with the sense of metaphysical betrayal experienced in the play, i.e. personal disorder equals worldly, universal disorder. At the turn of the 20th Century, William Butler Yeats wrote the above dismal lines, giving voice to the feeling of the age. Western Civilization entered the 20th Century feeling lost and betrayed. They had just faced the devastation of World War I, which confounded many people’s ability to make sense of the world. Yeats’s first stanza describes this anarchic world whose gravitational “centre cannot hold.” His second stanza raised the question few dare ask- what if the revelation we all long for to help us make sense of things represents not our salvation but our apocalypse? Is no story better than a horror story? 106748048 Page 2 of 5 And so, in his confrontation with the Ghost, Hamlet learns that he has the obligation to set things right. But how, exactly, to do this? It turns out this is a brain teaser. The Ghost warns Hamlet that in his pursuit of justice he must “not taint his mind.” Which brings up a problem- how do you act justly in an unjust world? How do you pursue truth in a world of lies? Horatio warns Hamlet that pursuing a Ghost is risky business, which might result in being lured to the brink of madness- and “deprive” his “sovereignty of reason.” It is reason that must, above all, not be lost in this game- according to Hamlet, his mother was “ a beast that wants discourse of reason” when she leapt into bed with her brother-in-law. We begin to learn the importance of reason- for we discover that there is nothing that in this world where nothing is as it seems, it is our mental powers of interpretation that give the reality and shape to things. The whole of Denmark’s reality is being shaped by a “forg’d process”. If one doesn’t preserve one’s mental purity, the whole gig is lost.. In the play, Hamlet decides to hide his wits and preserve his mental integrity by playing the fool and pretending to go insane. He discloses his plan to Horatio, and puts on his “antic disposition” with some regularity throughout the play. This isn’t as far fetched as it seems. On the one hand, it’s a good way to lighten up a playthe wise fool is a stock character in Renaissance plays. Almereyda’s movie by contrast is a fairly somber affair. But the wise fool serves more function than to lighten things up- the wise fool is free to expose the folly of those thought to be wise. In a world gone mad, the foolish begin to be the wise ones. MUCH madness is divinest sense To a discerning eye; Much sense the starkest madness. ’T is the majority In this, as all, prevails. Assent, and you are sane; Demur,—you ’re straightway dangerous, And handled with a chain. Emily Dickenson On this score, Polonius is perhaps not as dim as we tend to think. In fact, he is just clever enough to be dangerous. After having urged his son with the dictum, “To thine own self be true,” he proceeds to hire someone to spy on Laertes. Nice dad! Not only does he ask Reynaldo to keep tabs on his son, but he gives him wide latitude in his choice of approach to the task, encouraging him to be dishonest if he needs, and by “indirections find directions out.” In a crooked world, one must use crooked means. Within this context, Hamlet’s “antic disposition” makes even more sense. To preserve his rational mind, he must bury it in folly, lest it grow dishonest. Hamlet equivocates through puns, not through dishonesty, which allows him to slip and slide through the snares that have been set for him until he is able to 106748048 Page 3 of 5 act. Hamlet also employs another tactic loved by English majors: the parodox. In his letter to Ophelia, we read the cryptic words: Doubt thou the stars are fire Doubt that the sun doth move Doubt truth to be a liar But never doubt I love. If even truth must be suspected of lying, then the world is truly out of joint. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, sent by the King & Queen to find out what’s wrong with their brooding son, lack even Polonius’ sophistication, and Hamlet soon makes verbal and literal mince meat out of them. Ironically, in his conversations with them, he does, in actual fact, reveal the source of his ill will, though they are too stupid to recognize it, a fact which Hamlet is probably banking on. In his speech, his words anticipate Satan’s speech in Paradise lost when he muses that Denmark is a prison to him, “for there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.” HAMLET Denmark's a prison. ROSENCRANTZ Then is the world one. HAMLET A goodly one; in which there are many confines, wards and dungeons, Denmark being one o' the worst. ROSENCRANTZ We think not so, my lord. HAMLET Why, then, 'tis none to you; for there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so: to me it is a prison. ROSENCRANTZ Why then, your ambition makes it one; 'tis too narrow for your mind. HAMLET O God, I could be bounded in a nut shell and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams. Act 2 sc 2 This is the clearest expression of the sovereignty of reason for these scholars, and it’s a direct challenge to the earlier medieval ontological view of the world. Ontology is a philosophical term that refers to the essential qualities of a thing. An ontological view of the world posts that things have a specific, essence that defines their being. Things are not good or ill depending on how you look at them. Things are good because the ARE GOOD or bad because they ARE BAD. Hamlet’s relativistic view of the world allows causes him to suspect the Ghost’s words. We cannot tell if this is ontologically a good ghost or not. Therefore, he decides, following in 106748048 Page 4 of 5 the scientific empirical tradition, to run an experiment. What reason cannot find out, observation will. Stage a play that is frighteningly like the actual murder, observe Claudius’ reaction, and draw conclusions based on observable evidence. For controls, call in another observer, Horatio- Hamlet’s scholastic buddy. Thus, “the play’s the thing that will catch the conscience of the King.” Of course, the word “play” contains its own sense of play. It’s Hamlet’s word play, antic play, and game-playing that will catch this king. And so the game is a-foot, and everyone is watching everyone else, with Hamlet, in Ophelia’s words, “the observed of all observers.” Hamlet’s speech to the actors is in some sense a speech to himself, reminding himself to “suit the action to the word,” and not overdo the part he is playing. Art’s function is mimetic, to hold the mirror up to nature, exposing its virtues and follies. 106748048 Page 5 of 5