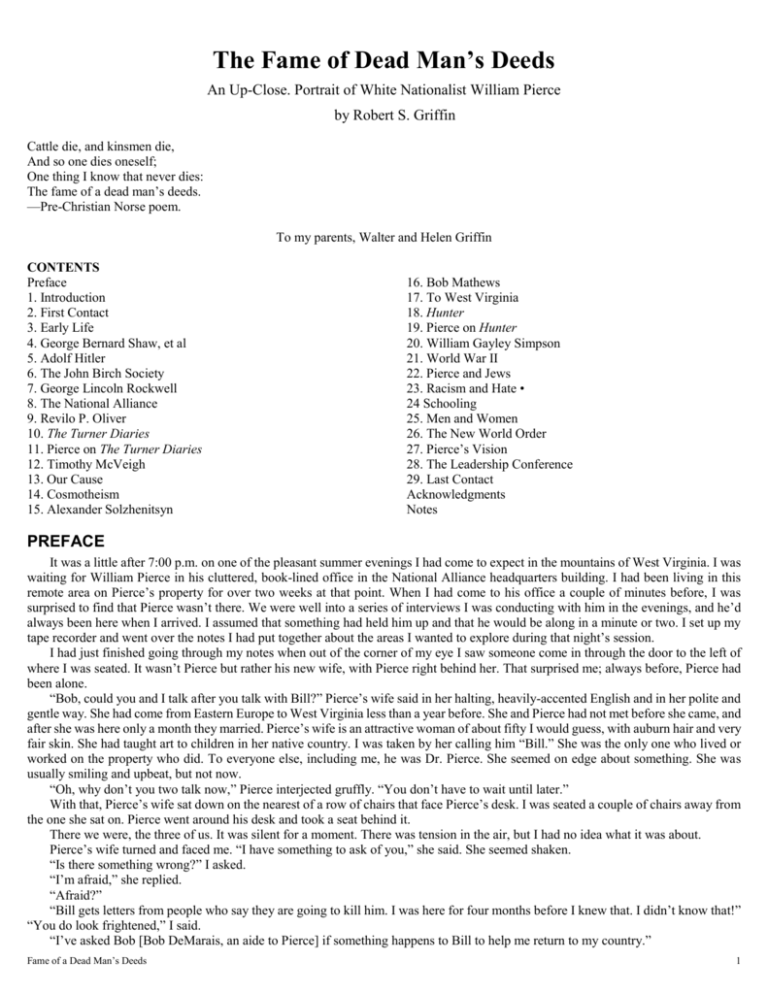

- JRBooksOnline.com

advertisement