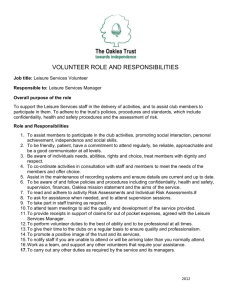

integrating work and leisure

advertisement