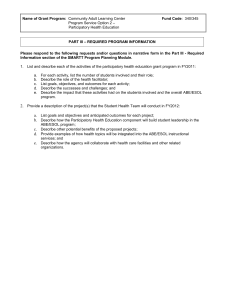

The ABE Curriculum Framework - Massachusetts Department of

advertisement