ADR in the Civil Justice System Issues Paper March 2009

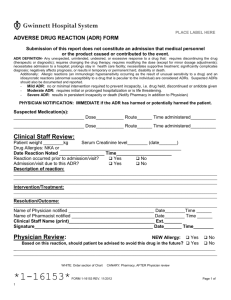

advertisement