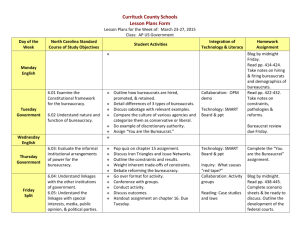

Warwick: A Theory of Public Bureaucracy

advertisement