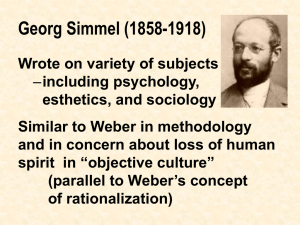

Georg Simmel, 1858-1918

advertisement