Burd_UCF-NCA-Preconference-2014_Full

advertisement

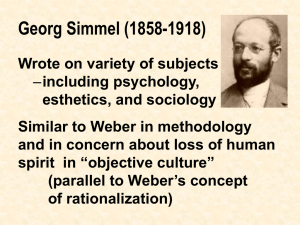

SOCIAL MEDIA AND MENTAL LIFE IN THE NEW MEDIAPOLIS What Might Simmel Say Today in his Seminal Essay ? by Gene Burd Belo Center for New Media University of Texas Austin, Texas Position Paper for Seminar on Urban Communities in Conflict and Dialogue Urban Communication Foundation National Communication Association November 19, 2014 Chicago, Illinois As we ponder and predict how the Internet and social media are leading us into a new urban geography of mediapolis and computerized cyberspace, it might be useful now to revisit, reassess, reinforce, or even reject, or refute Georg Simmel’s classic seminal essay-lecture on mental life in the metropolis delivered 111 years ago in Dresden. Simmel unexpectedly told his surprised audience in 1903 how the city affected their “metropolitan public lives” rather than their effect on it. He told them that his discussion of “the soul of the cultural body. . . .will be my task today”. He described intense urban stimulation, the deep emotion of the heart felt in rural and small towns compared to the blasé city’s control of time, money and intellect. His lecture was not a research report, but more of a “position paper” , raising questions, rather than reporting conclusions from a sophisticated study. Posing pertinent questions often means as much as providing their answers. 1 Simmel’s paper was presented more than a century before the arrival of the Internet and social media and long before use of the term “mediapolis” in 2006 by Roger Silverstone, a British media economics scholar, who was more concerned with media’s role in ethical and moral global justice through diversity than with the common communication issues of the nation-state. Simmel saw communications technology expanding existing public interaction and geographical space in a common megalopolis. Questions might be asked today of Simmel (1858-1918) if he had lived in this past century. Keep in mind that his seminal essay and his other ideas related to cities and media in a “BC” period: before computers on which these words are composed—and before television, the Internet, facsimile, Xerox, e-mail, voice mail, social media and before many advances in radio, telegraphy, telephone, photography, and movies; plus before the full arrival of the wheels of autos, wings of planes, and flights into outer space. He could not be expected to have responded to Samuel F.B. Morse’s question as to “What hath God wrought?” when the telegraph was invented 14 years before Simmel was born; or to responsibly assess the significance of Alexander Graham Bell’s request to Watson in 1976 to “Come here. I need you” , when Simmel was only 18. Simmel’s ideas covered a bewildering and dizzying variety of interdisciplinary topics in urban life uncluding money, fashion, art, fashion, love, flirtation, mealtimes, strangers, shame, prostitution, greed etc.. He defied “disciplinary containment in his unconventional writing style and methodology” and he wrote in a disorganized manner. His sociology was “thought to be disjointed and over-concerned with the ephemeral and mundane” in his favored essay format yet the significance of “Simmel 2 in Cyberspace” “remains woefully overlooked in studies of computer-mediated communication (Feldman). He has been called “the unfairly neglected founding father of sociology” (Frisby; Mackonyte), although there are understandable limits to his and other human predictions on the future consequences of their current technology. Both minds and machines---and of course the metropolis-- have changed since Simmel’s time. Urban “mental life” has been modified far beyond the geographical space of 19th Century “city limits” to encompass a global world in which we now re-think old notions of cities and communication. Simmel’s early grasp of the significance of space in the city beyond physical geography (Borden) was and is belatedly recognized. The notions “in his fertile mind” of the geometry of social distance influenced journalist Robert Park and others creating “The Chicago School of Sociology”—a reminder conveyed in a paper here in Chicago 29 years ago yesterday at a convention of the Social Science History Association (Ethington). Another reminder of significant urban ideas presented here was Frederick Jackson Turner’s paper 121 years ago on the end of the frontier at the 1898 meeting of the American Historical Association during the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. “In a sense, the Internet is an extension of the metropolis as Simmel saw it.“ (Lehrer). It becomes the site where autonomy struggles with anonymity. . .The Internet Metropolis strips away opportunities for individuation and gives us commodities. . . . The Internet milieu prompts us to package ourselves so that we can recognize ourselves having a identity. Of course, that is where Facebook comes in.” (Horning; Lehrer) helping social media users 3 and advocates to rescue discourse, emotion and intimacy lost in mass mediation, and to restore the spontaneity of the non-verbal (Andrews). The emotional viscera, heart and “soul of the cultural civic body” of Simmel’s “psychic existence beyond technical mediation” might expand more into the following urban communication settings: Flesh, frowns, flatulence, voice, touch, sighs, smiles, sounds and smells; handshakes, hair-cuts, hugs, halitosis, hitting, kissing, kicking plus various body slaps and body-odors, blinks, belches, bows and bumps, glances, gazes, and glares; nods and sighs, slouching, spitting, folded arms, crossed legs, hands in pockets, teasing, taunting, variations of the middle finger) shaming, shunning, inviting, ordering,; leanings, facing, winks, whines, and waves; yells, cries, moans, and seldom studied postural interactions in elevators, escalators, lavatories, lobbies, cars, rest stops and sidewalks. Also, what may be the consequences from the dissolution of established communication patterns, such as the natural voice, hand-writing and public clocks as new media extend, but may extinguish interpersonal communication ? Consider also the urban blasé of narcissus “bowling alone” in light of Putnam’s classic landmark 1995 seminal essay turned into a 2000 book in which he described the decline of social capital—a concept first used by urban journalist Jane Jacobs before being credited later to social science scholars. (Putnam, 1995, 2000). Simmel’s landmark essay did not fit the expectations of other scholars at Dresden and he was seen as an oddball sociologist off in all directions. Simmel’s intuitive and descriptive analyses pre-dated the anti-septic refereed survey research of the following century. Although not duly credited or referenced, Simmel’s concerns have been reflected in the lengthy lament and alarm in published anxieties of alienation in America over the last 60 years.—often in the context of urban communication. “Community has become both emotional withdrawal from society and a territorial barricade within the city. The warfare between psyche and society has acquired a real 4 geographical focus, one replacing the older, behavioral balance between public and private” as “The new geography is communal versus urban” …(Sennett, 1974). Some have argued that “hyper-individualism rather than urbanization has obscured the idea of community’ (Bellah et al). Alarms range from the inner and outer in the “lonely crowd” (Reisman 1950); to the alienated “bowling alone” (Putnam, 2000); to being “alone together”. (Turkle 2011). One view is that “in a large sense people themselves have become the mass media” through use of social media like Facebook and Twitter, about whose impact, the jury is still deliberating on how those social media affect the inner-directed (rural-small town) and the outerdirected (cosmopolitan) character (Hiebert 2014). Alarm has reined, rained and reigned on the pursuit of loneliness often in urban settings (Slater, 1970); in the more rural rampant habits of the heart (Bellah et al,1985) ; in the fall of public man being moved through public space, yet not be “in” it (Sennett, 1974); and in the separation of bodily flesh from city stone (Sennett, 1994); in the forbidden public touching of skin (Montague, 1971)—except with pets and perhaps in pornography. Concern arose over news produced from nowhere (Epstein, 1973); the emergence of the private future (Pawley, 1974); the rise of the image and the fall of the word (Stephens, 1998)—the decline of letters and handwriting; and the end of conversation via face-to-face dialogue (Ferrarotti, 1988; Burd, 2012); the death and extinction of discourse in a wired world as the exchange of reasoned thought and reflection are replaced by “verbalized expression and ritualized stylistic performances” (Slayden & Whillock, 1999). We were reminded that “Virtual reality calls into question our very notion of authenticity” 5 (Jones; Hardt, 1993); with an obsessive communication overload for the online person-- formerly a flesh and blood self, now dead to the real world while pouring attention into a cell phone. Some say the digital life robs people of solitude and daydreaming with their own thoughts—thereby bringing the end to solitude and absence (Harris, 2014), with solitude in self-reflection “interpreted as an illness that needs to be cured (Turkle), Perhaps here, some past, present and futuristic personal historical anecdotes can serve as useful anti-dotes to counteract the current epidemic of technocratic scholarship, which still frowns on historical autobiography as a research methodology. As a journalist (or generalist) I am more social than scientist, so permit me a few autobiographical citations, ideas and scattered range of topics which might relate to this session on past, present and future dialogue in urban communities. I was a very isolated rural farm boy until age 14 in the rural Ozarks, in the 1930s, where lightning was the only electricity, where we went outside to defecate (with no outdoor “plumbing”), where the only running water was in a creek, and where you spoke to everybody—a practice that caused some to question my sanity So to speak) when I did that in the early l940s as a new Los Angeles resident, where I at first spoke to everyone in public (so to speak)--- I was not blase but mentally unstable; as I soon learned that the heart emotion) belonged in the country but the head ( the mind) belonged in the city. As a student in a sociology class at UCLA, I first read (and quickly understood) Simmel’s newly translated essay. Our similar cultural pasts, eclectic interests and urban focus fascinated me and influenced my career in journalism as he had done 6 for journalists like Robert Park (one of Simmel’s students) who helped establish the early bases of the Chicago School of Sociology in the early 1900s. with others at Jane Addams’ Hull-House where I was later to live in the early 1960s. Later New York City “taught” me about urban life in the early 1950s, and I often visited nearby Bryant Park (Keith Hampton’s research site 60 years ago) during breaks from ushering at a nearby Times Square burlesque theater and delivering books (not yet e-books) for a book store just east of the lions statues of the public library. In those days people often spoke and connected to strangers. That was before cell phones, electric mail and on-line shopping ,when there were still post offices like that huge one adjacent to J.C. Penney’s mail order offices on 34th Street where I was one of his office mail boys and got to know him—and his advice for career success. (Decades later when I was in New York, Penney headquarters had moved to Dallas, it was no longer safe to stroll at mid-night in Central Park and Bryant Park had changed —but at that same old theater, the same chewing gum was still glued under the seats). My maternal grandmother was 23 when Simmel was born, and when she learned how to use a phone, she called me hundreds of miles away and remarked in amazement: “I can hear you, but you are not even here.” I reacted similarly in the early 1930s, when I heard the radio voices of Hitler ad his marching drummers, Churchill’s deep voice, and FDR’s resonant Pearl Harbor and D-Day Invasion speeches—not seeing he could not even walk. One day in the early 1940s, my brother excitedly told me he’d seen a tiny box in an East Los Angeles Sears display window showing moving pictures. I said it was probably a movie but not in a theater, to which he exclaimed: “But It’s happening while we are watching” . That reminded 7 me of my farmer Dad chiding the periodic traveling movie operator flashing scenes of actors in an abandoned hall room on a hanging bed sheet screen where my Dad saw movie actors about whom he said “They don’t mean it. They are all lying”. More history on screen in the late 1960s, with astronauts reading Genesis scripture from outer space and pictures from the moon telling us the earth was indeed round—like the globe in that one-room school. Then came the first word spoken on to the surface of the moon by Neal Armstrong. It was the name of a city—Houston-- where I had been a reporter in the late 1950s. Still later in the age of new media, I recall in the early l970s, an excited professor arriving late to our annual faculty party excitedly telling us that a new gadget on campus had connected Christ and Japan as keywords. It was the Internet ! Communication history continued years later when one of my journalism students wrote a story about an interesting student in her dorm who she said was often up late at night “constantly pecking on some noisy machine”. That student was Michael Dell. New media experience continues on the street as I walk seven miles each — without texting. Once, when I complimented a mother strolling with her baby saying “Oh, what a beautiful child”, she objectively responded by saying: “But you should see his picture”. As a breast baby, I called attention to a mother breastfeeding her baby as a “beautiful sight”, but a nearby porno film artist and viewer called public breastfeeding obscene. Nearby a couple on a bench held one hand with the other, while their other hand held a cell phone—on which they were both talking on their own phones—to each other. If technology in such close quarters inhibits close visceral communication, what does it mean for even more distant 8 communication ? Is geography and physical contact obsolete, ? Will the new technologies enhance or reduce Simmel’s concept of blasé ? Why even meet together here in a geographical place instead of just on-line ? Have “here” and “there” lost their meaning? Is conversation in physical space at an end and with what effect—negative or positive ? Will talking voices from bodies of flesh be forbidden, as mainly robots communicate with each other? Is there no need for contact in physical and geographical place and resulting contacts ? If the city is merely a “mental state”, then perhaps the city is like the human body, in which the imagination is perhaps the most significant sex organ in the physical body— indeed mind over matter---like the late comedian Joan Rivers suggested that the best birth control method was just to “leave the lights on”-- and let the imagination work. Will the new media fixation on the self force us to drown in eccentricity with Narcissus or flee to Walden Pond with Thoreau to get away from the Internet ? Is the city (of Simmel’s day) and today obsolete as a place, if the individual alone is a place, in which the MEdia and the SELFie merely humanize the new technologies like the personal Kodak camera freed people from dependence on artists for portraits and “art”. Remember that Gutenberg et al allowed the masses to communicate with God without going through the priests. Today “In a large sense, people themselves have become the mass media . . (Hiebert)., and social media makes everybody a journalist (Gant 2007) thereby extending McLuhan’s mantra in the early 1960s when he reminded us that the medium itself is the message. People then became “digital” (Negroponte 1996) as MEdia. and SELFie melt and 9 merge media, message and mankind into one metropolitan space and place-- perhaps in Bryant Park. ? If the new technologies can replace previous communication patterns, and if they make place, space and time non-essential to communication, city and community, and if we eliminate the geography of cities, then why meet for these conferences if communication can take place virtually on-line ? Where is here and does it exist or even matter anymore ? Perhaps the city will disappear since “What once had to happen in the city can now take place anywhere” since the new technologies “will soon begin to provide excellent substitutes for face-to-face contact, the chief remaining reason for the traditional city” whose “advantages of proximity for human interactions will continue to decrease.(Pascal, 1987). One response to Gertrude Stein’s complaint that Oakland had no there there, is that “There is less and less there anywhere, anymore. Increasingly, there is everywhere” . We have been told that “Academic observers . . .should stop worrying about the viability of cities. A system will survive even if it differs from the system we know” (Pascal, 1987). Some critics in nostalgic reflection about a more pastoral civic past and the “urban localism” of “meeting people”(Bellah et al) say that such observations are nostalgic and idealized “sociology without data” , and are “not responsible sociological analysis” and may be a “useful journalistic paradigm, but not good social history”, which presumes that if we have “Intellectual brilliance and deep moral concern. . . who needs data!” ? (Greeley, 1992). Although online social networking without non-verbal cues has been criticized, some recent research 10 by social neuroscientists show for example that on-line meeting, dating and marriage are more likely to last longer than reliance on the myth of love at first sight. A University of Chicago professorial couple (John and Stephanie Cacioppo) did the study, after meeting on-line and are now happily married (Sapolsky, 2014). So, what might Simmel today, if new communication technology replaces public interaction in a geographical place ? One argument is that “ We need face-to-face interaction. It is crucial to our intellectual and social development, it allows for the development of richer contexts between people in which more intricate details and meanings can be shared, and it provides certain satisfactions that are impossible to technologically replicate” (Chayko, 2002). Studies show that 93% of authentic (“real”) communication is based on non-verbal body language but “Awash in technology, anyone can hide behind the text, with e-mail, the Facebook post or the tweet, projecting any image they want and creating an illusion of their own choosing. . . with superficial abbreviations, snippets, and emoticons outside of real life like on a golf course with its “deeper. and more authentic relationships” (Tardanico, 2012). If there is no need for alarm, how might we react to such recent events as the Dallas hospital crew diagnosing and treating the Ebola patient at bedside while relying solely on their text messages without even talking to each other next to them; the California woman who lodged herself in the chimney of the house of a man she’d met on line, dated, and sought; or the high school student who invited classmates on-line to join him to dine, and then proceeded to shoot them. As traditional face-to-face communication is replaced by mediated communication and 11 social robots, more may be expected of technology than of each other as less urban social interaction creates the illusion of companionship without the demands of friendship as people talk to machines as the real and simulated life are not differentiated (Turkle, 2011). Perhaps eventually people will only touch and communicate with their pets which they can control. If “Simmel Says” he has a new message, would it be like the child’s game “Simon Says” where Simon issues instructions to players, who are eliminated if they fail to follow commands rather than their failure to act--- as the last player is the winner who followed all the commands. If only machines give obeyed commands to other robotic machines, perhaps that hated human halitosis will be hopefully halted or harnessed as we enter and fully embrace post-human, robotic urban life. Do we merely “Let Georg (Simmel) do It” , or do we wire Sam Morse to ask “What hath God wrought ?” or do we make a cell phone call to “Mr. Watson” and ask for a map to the golf course or Walden Pond—where we can ponder the placeless urban Internet in the new “City of Netropolis” ! REFERENCES: Bellah, R.N. et al (1985). Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life. University of California Press: Berkeley, CA. Borden, I. (1997, Winter). “Space beyond: Space and the city in the writings of Georg Simmel.” The Journal of Architecture 2:313-335 Burd, G. (2012, May 24). “Will new media technologies replace urban conversation ? International Communication Association, and Pre-conference for Urban Communication Foundation, Phoenix, Arizona Chayko, M. (2002), Connecting: How we form social bonds and communities in the Internet age, State University of New York: Albany . Epstein, E.J. (1973). News from nowhere. Random House (Vintage), New York, NY. Ethington, P.J. (1997) . “the intellectual construction of ‘social distance’: Toward a recovery of Georg Simmel’s social geometry, Cybergeo: European Journal of Geography, <http://cybergeo.revues.org/227> Feldman, Z. (2012, March). Simmel in Cyberspace, Information. Communication 12 & Society, 15:2, 297-319. Ferrarotti, F. (1988). The end of conversation: The impact of mass media modern society. Greenwood Press: New York. Greeley, A. (1992, May/June). Habits of the head. Society, Society, pp. 74-81). Hardt, H. (1993). Authenticity, communication and cultural theory, Critical studies in mass communication, 10:1, 49-69. Harris, M. (2014) The end of absence: Reclaiming wat we’ve lost in a world of constant communication. Random House-Penguin. New York, NY. Hiebert, P. (2013, October 17) The Lonely crowd of social media, Pacific Standard. Horning, R. (2010, Sept. 16). “Simmel’s ‘The Metropolis and Mental Life’”. <http://www.popmatters.com/post/131028-/> Jones, S. (1993). A sense of space: Virtual reality, authenticity and the aural. Critical studies in mass communication, 10:1 (238-253). Jones, S. (1997). (Editor) Virtual culture. Sage: London. Mackonyte, G. , Georg Simmel: The metropolitan way of life in theory and practice Montague, A. (1971). Touching: The human significance of the skin. Columbia University Press, New York, NY. Negroponte, Nicholas (1996). Being Digital. Vintage: New York, NY. Non-Verbal communicaton modes BSAD 560, Intercultural Business Relations. http://www.andrews.edu/-tidwell/bsad560/Non-Verbal.html Pascal, A. (1987). “The vanishing city”, Urban Studies 24: 597-603. Pawley, M. (1974). The private future. Random House, New York, NY. Putnam, R.D. (1995, January). “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital”, Journal of Democracy 6:1, 65-78. Putnam, R.D. (2000), Bowling Alone: The collapse and revival of American community, Simon & Schuster: New York, NY. Sapolsky, R. M. (2014, October 18-19). Wall Street Journal “With tweets as with talk, emotions still moves us, p. C2; “Love at first sight is a myth, say Chicago Researchers,” The Neurocritic , 2014, February 22). Sennett, R. (1974). The fall of public man. Alfred A. Knopf. New York: NY. Sennett R. (1994). Flesh and stone: The body in the city in Western civilization, W.W. Norton: New York, NY. Silverstone, R. (2006). Media and morality: The rise of the mediapolis. Polity Press: Malden, MA. Simmel, G. (2903). The metropolis and mental life, Adapted by D. Weinstein from Kurt Wolff (Trans.) The sociology of Georg Simmel. Free Press: New York, 1950. Sladen, D. & Whiullock, R. (Eds) (1999) Soundbite culture—The death of discourse In a wired world. Sage: Thousand Oaks CA. Slater, P. (1970) . The pursuit of loneliness. Beacon Press, Boston, MA. Stephens, M. (1998). The rise of the image: The fall of the word. Oxford University. Taranico, S. (2012, April 30). Is social media sabotaging real communication ? Forbes <http://www.forbes.com/sites/susantardanico/2012/04/30/is-soci> Turkle, S. (2011), Alone together: Why expect more from technology and less from Wachter, R. (2014, Oct. 13). How not to treat ebola in digital age. USA Today (6A) 13 14