Green Jacket Project: Two Examples

advertisement

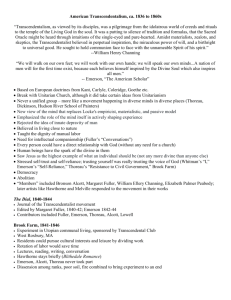

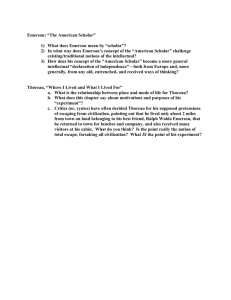

TRANSCENDENTAL MINI ESSAY EXAMPLE: JOHN CAGE DECONSTRUCTION SETUP PARAGRAPH #1 – Explanation of Transcendental Quote TOPIC SENTENCE In his essay “Nature,” Ralph Waldo Emerson examines a key component of the transcendental philosophy—namely, the tranquility, divinity, and discovery of self that nature can provide in our lives. However, he qualifies this idea by suggesting that our relationship with nature is just that—a relationship between two parties in which each affects the other. D&E #1 He points out that nature does not show up for us “always tricked in holiday attire”; rather, it “wears the color of the spirit,” meaning our “spirit” (Emerson 3). C #1 By personifying nature as a person who isn’t going to automatically don a fancy holiday party getup for us, and that in fact, our “spirit” helps shape nature’s appearance, Emerson reinforces the idea that our connection to nature, in part, depends on our outlook, attitude, and emotions. D&E #2 He imagines that someone “laboring under calamity” or mourning a friend’s passing may feel “contempt” for his or her natural surroundings and even see the sky as “less grand” (3). C #2 Emerson’s examples help to make his theory universal because almost all of us have experienced a relationship with nature that was altered by our “spirit,” whether it was a tree we loved because of happy climbing memories, a light drizzle of rain that seemed magnificent because we scored a home run, a scenic mountain range we came to hate because of an ugly fight on a family hike, or a glorious sunny day ruined because a crush broke our heart. PARAGRAPH #2 – Applying the ideas of the Transcendentalist Quote to Into the Wild TOPIC SENTENCE In his literary nonfiction biography Into the Wild, while using a story from his own youth to explore, explain, and even defend, modern-day transcendentalist Chris McCandless, Jon Krakauer describes climbing Alaska’s Devils Thumb—an experience that reflects Emerson’s theory on our conditional relationship with nature. D&E #1 When describing the mental state he enters when taking on the danger of a risky climb, he claims that the feeling of peril “bathe[s] the world in a halogen glow,” elevating “the sweep of the rock, the orange and yellow lichens, the texture of the clouds to stand out in brilliant relief” (Krakauer 134). C #1 Someone else might have a very different relationship with the austere crags and edges and high altitudes of a rocky mountain, but in Krakauer’s eyes, that same landscape—as Emerson argues— “wears the color” of his “spirit” (Emerson 3). D&E #2 However, when solo climbing one of nature’s summits, Krakauer is also very aware that he must make a “tremendous conscious effort” to greet the mountain with self confidence so that he can withstand the sensation of “the abyss pulling at [his] back” and become comfortable with “rubbing shoulders with doom” (Krakauer 142). C #2 Krakauer is fully aware that a mountain peak—no matter how magnificent—may not be “tricked in holiday attire” (Emerson 3). Like Emerson, he personifies nature as someone with whom the outcome of our relationship is contingent upon the outlook and attitude we bring to it. PARAGRAPH #3 – Applying the ideas of the Transcendentalist Quote to Fahrenheit 451 TOPIC SENTENCE Ray Bradbury’s science fiction novel Fahrenheit 451 also features scenes and passages that connect to Emerson’s transcendentalist belief that our experiences and emotions affect how we perceive nature. D&E #1 In the book’s final section, Guy Montag is a fugitive on the run, wanted for harboring books and for the murder of his boss, fellow firefighter Captain Beatty. To escape the mechanical hound that is tracking him, he jumps into a river and lets it pull him downstream. Finally away from the city and no longer required to defend the society’s practice of destroying books and the ideas contained in them, Montag senses that he is “moving from an unreality that [is] frightening into a reality that [is] unreal because it [is] new,” and as a result of this fresh perspective, “[f]or the first time in a dozen years” he sees a “juggernaut of stars” that “threaten to roll over and crush him” (Bradbury 140). C #1 While the mood created by most descriptions of a starry sky is typically romantic and peaceful, but because Montag’s previous life never really allowed him to have a relationship with nature, Bradbury uses diction that evokes a sense of oppression to paint a picture of a night sky that, similar to Emerson’s example, is not only “less grand” but even menacing (Emerson 3). D&E #2 Nevertheless, as Montag continues to float farther away from the emptiness and misguided thinking of his past, the river “[holds] him comfortably and [gives] him the time at last, the leisure, to consider…a lifetime of years” in his future (Bradbury 140). C #2 In this scene, Bradbury contributes his own fictional illustration of Emerson’s ideas. When Montag is “laboring under the calamity” of escaping death and encountering a natural world that is unfamiliar to him, nature appears as an antagonist. But only sentences later, as Montag adjusts his “spirit” (Emerson 3), his relationship with nature completely transforms when Bradbury personifies the river as a loving caretaker who is willing to “[hold]” this changed man (Bradbury 140).