Kingship and Counterfeit:

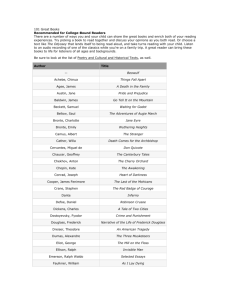

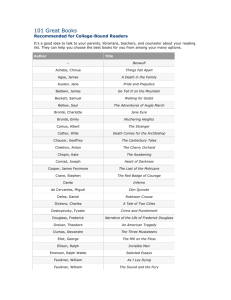

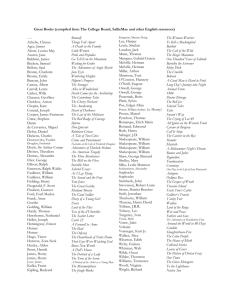

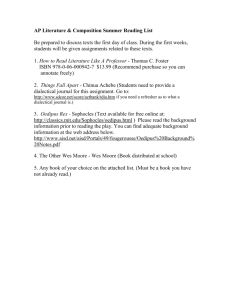

advertisement