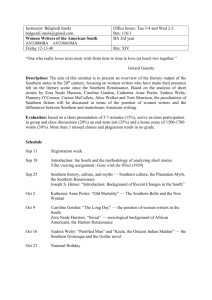

English 9 Course Outline, 2012-2013

advertisement

English 10 Course Outline, 2013-2014 Mr. Campbell, BD 409 Unit 1: Identity, Self-Discovery and Redemption (8-10 cycles) Explore ideas related to identity and growing up through short stories and a novel Review writing skills (grammar, using transitions, terms of literary analysis, writing a solid thesis and organizing an essay) Assessment: Essay commentary, analysis of short passages, brief quizzes Short texts: Jhumpa Lahiri, “When Mr. Pirzada Came to Dine;” Tim O’Brien, “On the Rainy River;” Amy Tan, “Two Kinds;” Ralph Ellison, “Battle Royal;” and other short stories, as time. Main Text: Khaled Hosseini, The Kiterunner Unit 2: The Language of “Fact”: Exploring Non-Fiction (approx. 4 cycles) Explore a variety of non-fiction writing (autobiographical, journalistic, travel, et al.) Understand the difference between fiction and non-fiction Review paragraph and essay writing skills Understand essential terms and concepts: subjectivity, objectivity, audience , tone, etc. Grammar and SAT work Assessment: essay/paragraph examining a non-fiction text, original creative non-fiction writing Texts: a variety of non-fiction articles covering a range of subjects Unit 3: “Darkness Visible:” The Tragedy of Macbeth (6-7 cycles) Review of literary terms and Shakespeare’s language Reading, performing and analysis Assessment: commentaries (paragraphs and essays) on key passages, quizzes, adaptation project. Main text: William Shakespeare, Macbeth Unit 4: Poetry and Creative writing (4-5 cycles) Explore features of different poetic forms Experiment with poetry writing Assessment: commentary writing, poetry quizzes, creative writing (original poems). Texts: selected poems Campbell 2 Alongside the expectations and policies laid out in the High School Handbook, these also apply: Class Decorum / Behavioral Expectations: The most basic practice essential to the successful working of this class, respect—for every class member and idea expressed—ought to be the watch-word for each of us in the room. With mutual respect as the guide, basic courtesies such as engaged listening (itself a worthy form of active participation in large discussions), turning off cell phones / electronic devices and tuning into class go without saying. To clarify, the expectations here are these: • When a classmate, teacher or guest is speaking to the class, no one else is speaking, but all are listening—for the substance of what’s being said, and for openings in which to add our own voices. • When in class, cell phones and all electronic devices are turned off and out of access. Unless asked to bring such devices for a particular class meeting, we should all be electronic device-free in class. Materials / Texts: Daily, we’ll all come with notebooks, pens and pencils, class folders and the texts under review. Late Work: Late work will not be accepted, except in the case of absences, or with prior approval well in advance, due to travel, or an overload of assessments, or a similarly compelling circumstance. Grading Semester 1: Daily Grade Summative 10% (citizenship, participation, homework, class work, journals, brief quizzes) 90% Semester 2: Daily Grade Summative Final Exam 10% (see Semester 1) 70% 20% (Semester 2 only) Manuscript Presentation: All formal writing assignments should be • typed or word-processed, in black ink; • double-spaced, with one inch margins; • set up MLA style, first page laid out as in sample which follows, • in 12 point font (Times or Times New Roman) and • stapled individually (e.g. each draft stapled separately, if portfolio submitted). Note: Assignment page length ranges always assume a minimum of 300 words per page. Todd Hunter Campbell [= STUDENT’S NAME] Dr. Richard Messer [= TEACHER’S NAME] English 631 Techniques of Fiction 6 November 2001 Eudora Welty’s Love-Worn Path In her brief essay “Is Phoenix Jackson’s Grandson Really Dead?” Eudora Welty makes clear the terms and foundation of her 1941 short story, “A Worn Path.” The answer, she tells us, lies in her main character’s own response to the question (1334). After having been asked by the nurse whether her grandson, for whom Phoenix has once again made her trip to town in search of medicine, isn’t in fact dead, Phoenix—only then reminded of the reason for her mission—states emphatically, “No, missy, he not dead, he just the same” (1333). As Welty makes clear, Phoenix’s response points to “the artistic truth” of the matter (1334), a truth which grows out of the underlying business of the story itself. Rather than asking whether or not the boy still lives, Welty seems to suggest, we ought instead to look more closely at where he lives, which comes clear in the grandmother’s journeying. As Welty notes, “The real dramatic force of a story depends on the strength of the emotion that has set it going. . . . What gives any such content to “A Worn Path” is not its circumstances but its subject: the deep grained habit of love” (1335-36). The real question, then, centers around exactly how Welty sets in motion the dramatic forces which carry her account of an old woman’s walk to town on behalf of a momentarily forgotten grandson—who may “in reality” have died three years ago—so that the story works on the archetypal level even as it follows the main character’s “habit of love.” Welty begins by devoting herself to the particulars of description, locating us immediately in “December—[on] a bright frozen day in the early morning” (1327). The crisp setting established, Welty turns our attention to a point “Far out in the country.” As she slowly pulls in closer on the “old Negro woman with her head tied in a red rag,” whose slow progress she then begins to trace through “the dark pine shadows,” Welty allows her own words to slow Campbell 4 down and be with the images she describes. The woman’s umbrella handle cane, with which “she kept tapping the frozen earth in front of her[,] . . . made a grave and persistent noise in the still air, that seemed meditative like the chirping of a solitary little bird” (1328). Already beginning to establish Phoenix’s close ties with nature and the animal world, Welty here makes clear the quiet that surrounds her, while the writer’s language itself takes on a kind of meditative quality as she lets it linger over the contours of her character’s face: Her eyes were blue with age. Her skin had a pattern all its own of numberless branching wrinkles and as though a whole little tree stood in the middle of her forehead, but a golden color ran underneath, and the two knobs of her cheeks were illumined by a yellow burning under the dark. (1328) Welty’s careful, loving description of Phoenix, grounded in the physical reality of her character’s body, works its way slowly through a series of ever deepening sense images to point to the “yellow burning” underneath her skin. Having moved momentarily into the realm of the spirit, and thus intimated the strength of purpose behind Phoenix’s journey, Welty ends the paragraph on a purely physical note. However, her delicate description of Phoenix’s hair, which “came down on her neck in the frailest of ringlets,” shows once and for all this narrator’s devotion to her subject. Appropriately enough, it turns out, Welty’s warm embrace of her character mirrors the openness with which Phoenix approaches the natural world around her, and also prefigures the love with which she undertakes her intermittent journeys to town. Literally talking to the animals—both present and imagined—as she goes, Phoenix shows an “in tune-ness” with nature which makes the whole world around her come alive. To “a quivering in the thicket” at her feet, she calls, “Out of my way, all you foxes, owls, beetles, jack rabbits, coons, and wild animals!” (1328). Phoenix, by naming all of these creatures and speaking directly to them, literally calls into being the animal world around her, and thereby ushers us into the world of her imagination, as the line between the two arenas begins to blur. She sees and addresses a buzzard—“Who you