Electronic Commerce and the Printing Industry

advertisement

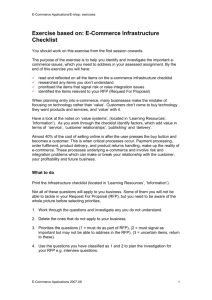

Electronic Commerce and the Printing Industry Ray H. Killam, CFSP, CFC This month, I read through the usual dozen or so magazines that I follow, including general business magazines such as Fortune, Industry Week, and Business Week, plus trade magazines such as FORM, Print On Demand, Papertronix, Inform, Strategy & Business, American Printer, and Infocus (the newsletter of the Business Forms Management Association). Each of these publications feature articles on business-tobusiness e-commerce. Throughout American industry, e-commerce is the hot topic, with virtually all companies seeking to develop a strategy. The printing industry is no exception. This paper discusses the specific challenges encountered by traditional “brick and mortar” businesses as they attempt to move into these uncharted waters. I then focus on the printing industry, which is an industry that faces no less than a complete reinvention of the way businesses (and individuals, for that matter) buy print. Faced with a serious onslaught by new “.com” companies, traditional industry companies have been slow to respond, yet have considerable opportunity for competitive advantage by staying focused on customers and working hard to meet their current and future needs. Electronic Commerce, A Managerial Perspective, (Turban, et al), sets the academic framework for business to business e-Commerce. The authors establish the supply chain management view as the central underlying factor driving B2B. Businesses in this model are using e-commerce to drive cost out of the procurement process, reduce time to market through just-in-time (JIT) availability of products, and to facilitate the efficient exchange if information between employees, suppliers, business partners and customers. Turban cites several successful business ventures that use e-commerce aggressively to accomplish these tasks. The book also contends that e-commerce will transform the way business is conducted throughout the world. While I completely agree with this rather aggressive contention, there will be many management challenges along the way that will enable some businesses to succeed while others will fail. For an excellent discussion on the organizational structure of the new “E Organization”, Neilson, et al, as published in Strategy & Business, a Booz, Allen & Hamilton publication, makes informative reading. Their “E-Organization Dimensions”, as outlined in the following chart, point out the range of organizational changes that will need to occur as businesses make the transformation to successful e-businesses. 1990s E.Org Organization -Hierarchical -Centerless, networked Structure -Command & Control -Flexible structure that is easily modified Leadership -Selected “stars” step above -Everyone is a leader -Leaders set the agenda -Leaders create environment for Leaders force change success -Leaders create capacity for change People & -Long-term rewards -“Own your own career” mentality Culture -Vertical decision-making -Delegated authority -Individuals and small teams are -Collaboration expected & rewarded rewarded Coherence -Hard-wired into processes -Embedded vision in individuals -Individualistic -Impact projected externally Knowledge Alliances -Focused on internal processes -Focused on customers -Individualistic -Institutional -Compliment current gaps -Create new value and outsource -Ally with distant partners uncompetitive services -Ally with competitors, customers and suppliers Governance -Internally focused -Internal and external focus -Top-down -Distributed Source: Booz-Allen & Hamilton Shikhar Ghosh, in his article “Making Business Sense of the Internet”, contends that the Internet presents four distinct types of opportunities: - Companies can establish direct links to their customers (which includes other businesses) - Technology lets companies bypass others in the value chain - It enables companies to develop and deliver new products and services to new customers - A company can use the Internet to become the dominant player in the electronic channel of a specific industry The above contentions are important for traditional “brick and mortar” companies to understand as they develop their going forward strategies for e-commerce. Yet, these issues also cause much of the reluctance and delays in implementing such a strategy. To understand this issue, it is helpful to consider the opposite to each of these opportunities: -Direct links to customers can cause serious disruption to established supply chain relationships, causing short term loss of profits and revenues -Technology can be used by competitors to bypass your company and reach out directly to your customers or drive down margins by more effective competitive bidding. Adoption of technology can be expensive or viewed as “too complicated” by traditional managers -Companies that do not traditionally drive new products and services to new markets may find that others are entering their “space” in ways not previously considered Companies that do not recognize that an electronic channel exists within their industry or are reluctant to drive the internal changes required by such a channel could lose out to a start-up “e-tailer” that has no such reluctance to abandon the traditional mindsets. Perhaps the biggest fear that exists in traditional brick and mortar companies is the fear of the unknown. “There’s almost no such thing as an established business model in e-commerce” (Wilder). Things are moving so fast that, unless you jumped in several years ago, it must seem as if there is no way to catch up. Trade press and conventional business press articles are using terminology and case examples that intimidate managers use to historical business strategies and understandable technology. For example, the stock market valuations afforded to many “e” businesses have no historical precedence. The fear of being “Amazoned” permeates more than one boardroom. In about 1995, Fortune magazine published an article that stated that American businesses had invested more than one trillion dollars over the previous thirty years in computer hardware, software and communications, yet had experienced a mere 1% improvement per year in white collar productivity. Senior managers were getting surly, expecting more for the amount of money invested. This led to a distaste for even more investment, particularly for some of the older managers. Y2K issues and concerns fueled this distaste for continued investment. As a result, some managers have been reluctant to view e-commerce as more than another "“fad” that will also pass over time. They couldn’t be more wrong. Most analysts attribute the current booming economy, accompanied by little inflation, to major gains in productivity achieved through this technology investment, with the Internet at the core of the action. Investment in the mid-to-late 1990s reached a frenzied pace, particularly in infrastructure building and ecommerce development. Most of the investment has been made in B2B. Fear of supply chain disruption as caused many companies to go slow with e-commerce investment. Recently, Home Depot, a major retailer based in Atlanta, sent a letter to their suppliers suggesting that suppliers that sold “direct” through the Internet would experience significant loss of business with Home Depot. General Motors and other automobile manufacturers risk upsetting their powerful dealer network if they sell direct through the Internet. Intermediaries in many businesses face loss of market share as their suppliers and manufacturers sell direct. Many businesses risk a loss of opportunity because they do not understand what e-commerce is and how it works. Their web sites (and most companies do now have web sites) are little more than on-line brochures that promote their products and do little else. They do not employ good web design techniques, do not understand that the web is a pull technology, not a push technology, and make it difficult for visitors to their site to place orders or communicate with the company. Heavy use of graphics, excessive text, lack of hyperlinks, and poor indexing and navigation slow response times and frustrate users. Another barrier to traditional businesses moving into successful e-commerce is lack of focus. Managers see the web as an opportunity, but fail to properly fund the investment or assign the proper priority. “One of the most common mistakes that companies make is simply adding E-business to a long list of responsibilities that someone already has” (Wilder, in a quote attributed to Laurie Windham, founder and CEO of consulting firm Cognitiative, Inc.). In other words, e-commerce development is added to the responsibilities of the CIO, or VP Marketing and is not viewed as a new discipline incorporating new skills and drawing from both IT and Marketing. This lack of focus delays investment, allocation of capital and human resources, and tends to get buried in the overall strategy. This view is again identified by Tapscott, et al, in their article “Rise of the Business Web”. They state “The real key to competing in the new economy is in business model innovation”. These “B-Webs” challenge traditional approaches to management, to business strategy, and to the roles of businesses in general. Their view seems to be pervasive throughout the literature. It is a new economy and we need fresh management innovation to compete successfully. This indicates that the most common impediment to e-commerce is the reluctance of management to innovate and move forward. There are additional forces that make it difficult for “brick and mortar” businesses to compete in ecommerce. Heavy past investment in infrastructure such as buildings, distribution channels, direct sales organizations, business processes, legacy computer systems, and training weigh heavily on maintaining the status quo and maximizing return of this investment. E-commerce is still relatively small in terms of total transactions processed, and it is easy to look at this and delay the additional investments required to move to e-commerce. Viewed in the historical sense, this makes sense. However, this does not stop the “new economy” companies, flush with all the venture capital they require, from inventing new ways to own any identified “space” on the Web, generally at the expense of those companies that are trying to maintain order in their existing market spaces. Many examples abound, with names of companies that didn’t exist a mere five years ago now garnering huge market capitalization, then using this new currency to buy additional businesses, including the old “brick and mortar” businesses. One has only to look to the recent acquisition of Time-Warner by AOL Corp. The printing industry in the US is a prime example of the clash between the old and the new. One of the oldest industries in existence, it is currently the second largest employer of all industries (second only to the fast food industry in the US). It consists of tens of thousands of firms, ranging from very large to very small. Firms can be full service, or highly specialized. Barriers to entry are relatively small, and the industry (at least in most segments) is quite mature and quite profitable. However, most segments of the industry are slowing down, and technology is beginning to have a sizable negative impact on overall growth rates, both from reduced demand for printed products and changing printing technologies. The remainder of this paper focuses on the printing industry and how traditional “brick and mortar” printing companies can take advantage of e-commerce, and the threats and barriers they face in this effort. Printing has many facets, ranging from the simple specification jobs to multi-component, complex specification projects. Many of these projects require that artwork, or “digital assets” be separately maintained and then associated with the proper component at time of production, thus assuring that the correct version or edition is printed. Many departments, individuals, and third party providers can collaborate on a complex print job, such as an annual report, training manual, legal file, and others. The Internet provides an ideal solution for collaborative communications. Companies that can harness this incredible power can achieve significant competitive advantage. Print technology is relatively unchanged since the days of Johann Gutenburg, the inventor of the printing press. Many practitioners still view printing as more art than science. It is primarily a craft. As such, printing has resisted change over the years. However, this concept is now changing rapidly. Digital printing has grown rapidly over the past twenty years and the advent of digital artwork files, coupled with the Internet for rapid deployment and distribution, is beginning to change the overall landscape. Thus, the industry is poised for a rapid transformation that is still not largely understood. Evidence of this impending change is rife. Digital pre-press, computer-to-plate technology, improving digital color presses, standardization of specifications, and rising demand for just in time manufacturing are beginning to drive this change. Nowhere is this pending change more evident than in the proliferating establishments offering print procurement, print requisitioning, and print development via the Internet. Companies such as Collabria (www.colabria.com), Impresse (www.impresse.com), Noosh (www.noosh.com), Printmarket.com (www.printmarket.com), iPrint (www.iprint.com), ImageX.com (www.imagex.com), and a host of others are bring e-commerce to the printing industry in ways not understood or embraced by the traditional “brick & mortar” printers. All of the above companies are new, have raised substantial amounts of venture capital (“Print On demand” magazine, January, 2000), are planning to go public soon, and are disrupting existing channels of distribution within various aspects of the printing industry. Many printers face the classic barriers to e-commerce, including large sales forces, strong distributor networks, entrenched management practices, multiple factories with large presses, and a belief that it is impossible to communicate design and production requirements for complex print jobs via the Internet. Some even believe that customers do not want to interact over the Internet. Consequently, few established companies have developed e-commerce solutions that involve end user customers in print development. In the past two years, some established firms have introduced e-commerce solutions for standard requisitioning of products from inventory (after they have been produced and stored), and for certain simple specification products such as imprinted business cards, stationery, and envelopes. However, none of these programs attempt to reach end use customers in the collaborative development of complex specifications. Yet, it is through this collaboration, and its ability to get the printer closer to customers, that true competitive advantage will be achieved. In some segments of the printing industry, specifically the business forms segment, suppliers have long wrapped services costs into product costs and have differentiated themselves on services provided. As the products matured, true differentiation on products has become very difficult. Now, the e-commerce “raiders” have introduced systems (based on the Internet) that allow end use customers to aggressively bid each job, effectively “unbundling” services from the product and driving down pure product costs to the point the product is becoming a commodity. I am convinced that, as is the case in many industries, e-commerce technology, philosophy, and innovation will change the way print is procured, produced and distributed. Print as a medium of information exchange is not endangered, as print revenues continue to grow (several industry sources confirm this assertion, including IBFI, PIA, Xplor International). What is also apparent from the industry trade journals referred to above is that few “brick and mortar” printing companies are leading this charge to e-commerce. In “ECommerce Rising” (Print On Demand, January, 2000), the author identified fifteen companies that are involved in various aspects of print-related e-commerce. Only two are traditional “brick and mortar” printing companies. All the rest are “.com” startups! Opportunities for some are perceived as threats by others. The ability to achieve competitive advantage within the printing industry will ultimately be determined by attitudes of management and their willingness to “cannibalize” existing channels, products, and institutions and embrace the new age economy at “Internet speed”. As is the case in many B2C industries today, the “click and mortar” companies have the early advantage and momentum. The old, established companies clearly must play “catch up”, or fall by the wayside. Bibliography: American Printer magazine, various articles, February, 2000 Form magazine, various articles, November, 1999 “The Forms & Document Industry-The Next 10 Years”, research report of the IBFI, Summer, 1999 Fortune magazine, various articles Ghosh, Shikar, “Making Sense of the Internet”, Harvard Business Review, March-April, 1998 InFocus, newsletter of the Business Forms Management Association, November/December, 1999 Inform magazine, Association For Information and Image Management, January/February, 2000 Papertronics magazine, IBFI, November/December, 1999 Print On Demand magazine, January/February, 2000 Strategy & Business, Booz-Allen, & Hamilton, First Quarter, 2000 Tapscott, Don; Ticoll, David; and Lowy, Alex; “Rise of the Business Web”, Business 2.0, November, 1999 Turban, Efrain; Lee, Jae; King, David; and Chung, H. Michael; Electronic Commerce: A Managerial Perspective, Prentice Hall, 2000 Wilder, Clinton, “E-Business: What’s The Model?”, InformationWeek.com, July, 1999