The Gift of the Magi by O`Henry

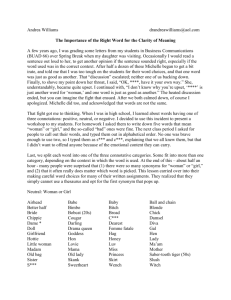

advertisement