Classical Music Period: Guide to Composers & Forms

advertisement

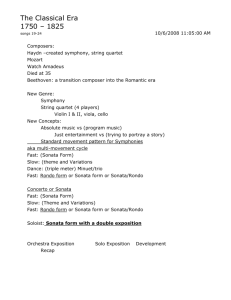

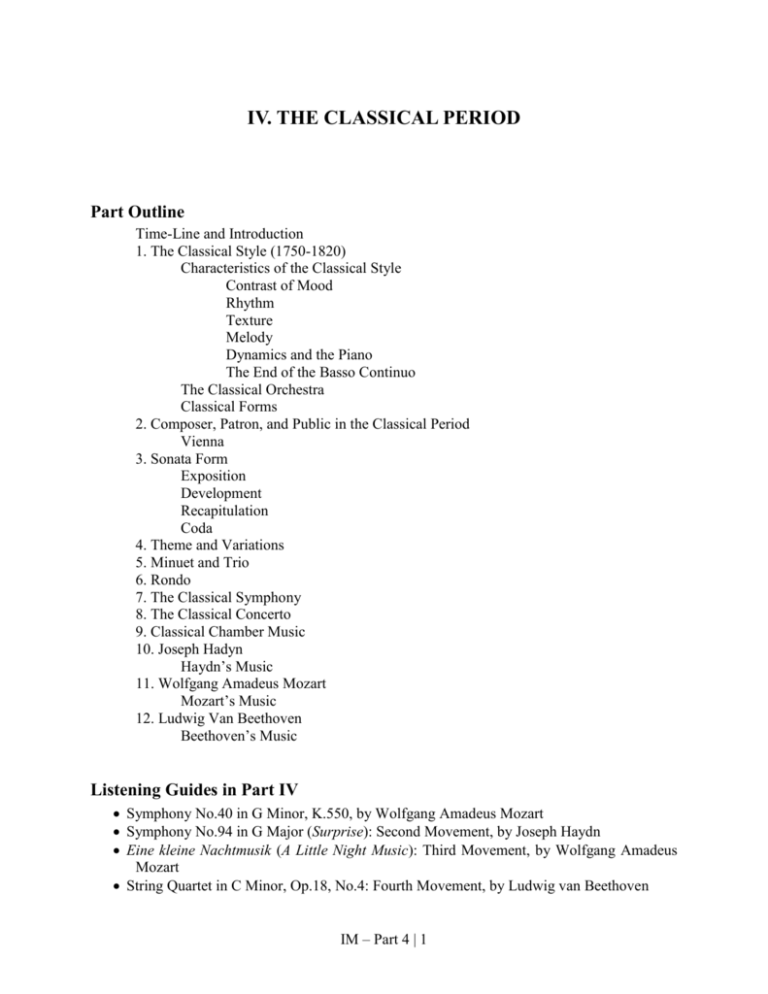

IV. THE CLASSICAL PERIOD Part Outline Time-Line and Introduction 1. The Classical Style (1750-1820) Characteristics of the Classical Style Contrast of Mood Rhythm Texture Melody Dynamics and the Piano The End of the Basso Continuo The Classical Orchestra Classical Forms 2. Composer, Patron, and Public in the Classical Period Vienna 3. Sonata Form Exposition Development Recapitulation Coda 4. Theme and Variations 5. Minuet and Trio 6. Rondo 7. The Classical Symphony 8. The Classical Concerto 9. Classical Chamber Music 10. Joseph Hadyn Haydn’s Music 11. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Mozart’s Music 12. Ludwig Van Beethoven Beethoven’s Music Listening Guides in Part IV Symphony No.40 in G Minor, K.550, by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No.94 in G Major (Surprise): Second Movement, by Joseph Haydn Eine kleine Nachtmusik (A Little Night Music): Third Movement, by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart String Quartet in C Minor, Op.18, No.4: Fourth Movement, by Ludwig van Beethoven IM – Part 4 | 1 Trumpet Concerto in E Flat Major: Third Movement, by Joseph Haydn Don Giovanni: Excerpt from Opening Scene; Madamina, by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No.23 in A Major, K.488: First Movement, by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Sonata in C Minor, Op.13 (Pathétique): First Movement, by Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No.5 in C Minor, Op.67, by Ludwig van Beethoven Terms in Part IV sonata form development coda minuet serenade symphony chamber music exposition motive theme and variations minuet and trio rondo concerto string quartet bridge; transition recapitulation countermelody da capo sonata-rondo cadenza IV-1. THE CLASSICAL STYLE (1750-1820) Objectives This section opens with a general survey of some nonmusical aspects of the classical period. The work of some great figures of the “age of enlightenment” is discussed, and the effect of these men on this age of revolution. The contributions of such rococo artists as Watteau and Fragonard, the neoclassicist David, and such socially conscious artists as Hogarth and Goya are evaluated. Bach’s sons are mentioned as representatives of the style galant, and their work related to that of the rococo artists. The problematical term classical is defined, and the remainder of the section seeks to define (often in comparison with the baroque) the various elements of classical style: contrast of mood, flexible rhythm, homophonic texture, melody, dynamics and the piano, the end of the basso continuo, the classical orchestra, and a general statement on classical forms. Discussion Topics 1. This section is designed as a general introduction to the classical period, and as such is quite self-sufficient. An exercise for comparing this period with the previous one may be found in the workbook, and it is suggested this be discussed either in class or as an assignment. 2. If you wish to discuss the style galant, you might compare one of the compositions of J. C. or K. P. E. Bach to Fragonard’s The Swing. The same pleasant salon style should be recognizable in both, and therein lay their charm. More importantly, in a course where nearly all works discussed are masterpieces, one needs the valleys to heighten the mountains. Listening to this light, unpretentious music, one develops a more genuine appreciation for Mozart. One could also mention that the style galant was the popular movement at the time of the founding of our nation. IM – Part 4 | 2 3. In discussing the general characteristics of the classical period, consider Jacques-Louis David’s Death of Socrates. The subject is taken from classical antiquity, the forms are clearly and realistically drawn, and the treatments are clearly objective (for background on the subject matter, see The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature, p. 399). 4. For more detailed information about specific composers, visit their sites via the WWW Virtual Library, Classical Music, Composers page, <http://www.gprep.pvt.k12.md.us/classical/composers.html>. The Eighteenth-Century Resources site, mentioned in IV-1.3 above, also has a special music index. 5. The workbook has a listening exercise to aid in comparing late baroque with classical works stylistically. It is suggested you play portions of three works in class, allowing sufficient time for the students to fill in the blanks while listening. Space is available for them to write in their decision as to which period they feel it should be, and for them to write in the title and composer (once you’ve told them), should they wish to hear more on their own. If you wish to have a baroque, classical, and style galant work, modify the chart accordingly. 6. Later, in the unit on Romanticism, the workbook has a research project to illustrate the changes that have taken place in the symphony orchestra. The students are asked to compare, and place in a seating plan, the instrumentalists called for in Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No. 5, Haydn’s Surprise Symphony and the Fantastic Symphony by Berlioz. The project can be introduced at this time with a comparison of baroque and classical ensembles. Questions and Topics 1. Describe the intellectual climate of the “age of enlightenment.” 2. Discuss the diverse meanings attached to the term classical. 3. Discuss the principal movements in the visual arts that spanned the period between the baroque and classical periods in music. 4. Discuss the characteristics of the so-called style galant. 5. Discuss some respects in which classical music differed from that of the baroque. 6. Rococo in art, style galant in music: a study in parallels. 7. The development of the orchestra during the classical period. IV-2. COMPOSER, PATRON, AND PUBLIC IN THE CLASSICAL PERIOD Objectives This section sketches the political and social climate of the classical period, an era that witnessed the French and American revolutions and the Napoleonic Wars. The musical taste and practices of the rising middle class are described, as is the influence of this middle class on the composers of the time. The section ends with a description of musical Vienna during the classical period. IM – Part 4 | 3 Discussion Topics 1. In discussing some of the political events of the time, you may wish to refer to the illustration of Goya’s The Third of May, 1808. Though painted in the classical period, the work has all the characteristics of romanticism. The subjective treatment of the scene puts the viewer squarely on the side of the peasants, even though this was a revolt against established authority and order as understood by the aristocracy at the time. The use of the lantern as a spotlight dramatically highlights the central figures: a person in an obvious martyr pose and a simple cleric, clearly suggesting that the common levels of the church (as opposed to the aristocratic bishops and princes) are on the side of the rebellion, and these are martyrs for a cause. Comparing this work with the Death of Socrates by David will visually show the differences between the classic and romantic spirits. 2. The status of the musician as a skilled servant can be discussed, using the situations of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven as examples (see “Haydn’s Duties in the Service of Prince Esterházy,” MWW 81). 3. A discussion of the rise of the middle class in this period can concern the question of musical tastes and fashion. For example, the middle class consciously attended public concerts and operas, and provided their children with music lessons to fit them for society. Ask how many of the students have had music lessons (assuming most of them consider themselves as “middleclass”), and how many public concerts and/or operas they have attended in the past year. Further, you may wish to question if, because of this class, they intend to provide such lessons for themselves or their children in the future (a good time for another commercial, if you have classes available for them to take, and opportunities for instrumental and vocal music making through classes or in community choruses, bands, or orchestras). 4. Paul Rice (Memorial University of Newfoundland) recommends the video Music of an Empire which shows the historical circumstances that made Vienna the musical capital of Europe (Man & Music series, FfH&S, ANE1773, 53 minutes, color). Should you wish to quote some writings from the period, the two excerpts from J. F. Reichardt (SSR nos. 75, 77) give fascinating insights into the musical life of Vienna and the major figures on the scene. See also “Vienna, 1800,” MWW 90. Questions and Topics 1. Discuss some political events and sociological factors that made the classical period such a time of violent upheaval. 2. Compare the means by which the three great classical composers supported themselves. 3. Discuss the role of the middle class in the musical life of the classical period. 4. If students consider themselves “middle class,” can they play a musical instrument, and will they provide music lessons for their children? 5. Describe the musical life of Vienna in the classical period. 6. Beethoven’s benefactors. 7. Haydn and the Esterházys. 8. Folk music in the classical period. IM – Part 4 | 4 IV-3. SONATA FORM Objectives A clear distinction is made between the sonata and sonata form (or sonata-allegro form). Sonata form is then divided into its three main components, exposition, development, and recapitulation, and the characteristic properties of each section are analyzed. The optional slow introduction and coda are also discussed. The section ends with a discussion of the first movement of Mozart’s Symphony no. 40 in G Minor, for which a Listening Outline is provided. Discussion Topics 1. It might be helpful to the students if you outlined sonata form on the board, showing the tonal plan as you do so (since the material is already in the text, this should be done quickly, as the students will not need to copy from the board). Later, while playing the Mozart movement, you can silently point to the various sections as they occur, without causing the mood to be broken. 2. As an illustration of sonata form, consider playing a short and relatively simple sonatina, such as the C major by Clementi. 3. Place the first movement of the G Minor Symphony in context, then play the movement once through for effect (8:12). It is recommended that multiple copies of the miniature score of the work be available, and after discussion using the text and chalkboard, students be encouraged to follow the score (with as much help as you feel the class needs, by circulating around the room helping students who might be lost, by calling out rehearsal numbers from time to time, or by pointing to the major sections outlined on the board). For home listening, draw attention to the Listening Outline in the text. In discussing the movement, you may wish to raise some of the following questions: can examples of sequence be detected in the bridge? What element of the first theme is present in the closing theme? How does insistent repetition contribute to the “closing” quality of this theme? How does the harmony contribute to the “closing” quality of this theme? Are there examples of sequence in the development? Where? Questions and Topics 1. Identify those movements of a multimovement work that are likely to be in sonata form. 2. Compare and contrast the exposition and recapitulation of a movement in sonata form. 3. Describe the nature of the development section of a movement in sonata form, and discuss the musical techniques that are likely to be found therein. 4. Describe the role of the optional introduction and coda often found with sonata form. 5. Thematic development in sonata form. IM – Part 4 | 5 IV-4. THEME AND VARIATIONS Objectives This section presents theme and variations form, and discusses some techniques by which a composer can vary musical ideas. The example given, complete with Listening Outline, is the second movement of Haydn’s Symphony no. 94 (Surprise). Discussion Topics 1. You may wish to include Mozart’s variations on Ah, vous dirai-je, maman (probably better known to the students as Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star), K. 265, mentioned in IV-I. Many CDs are listed in the latest Schwann Opus, and the music is easily available. 2. Another example, included in the set, is the theme and variations on “Simple Gifts” of Copland’s Appalachian Spring (see VI-15). 3. Depending on the sophistication of your class, you may or may not wish to tell the old legend about the reason for the “surprise” (Haydn supposedly said this would wake those who had fallen asleep during the performance). Do cover the Listening Outline, the basic techniques for providing variation, and the specific means by which Haydn provides variety yet maintains unity (6:14). The movement is included in the Videodisc Music Series edited by Fred Hofstetter and issued by the University of Delaware. 4. Another example, filled with humor but also illustrating various composer styles, is Edward Ballantine’s Variations for Piano on Mary Had A Little Lamb (2 vols., Boston: A. P. Schmidt, 1/1924, 2/1943). Vol. 1: Mozart (Agnelletto in C), Beethoven (Adagio), Schubert (Demi-moment Musical), Chopin (Nocturne (posthumous)), Wagner (Sacrificial Scene and Festmahl, from the tenth act of Lammfell), Tchaikowsky (Valse funèbre), Grieg (Mruks Klönh Lmbj), MacDowell (At a Lamb), Debussy (The Evening of a Lamb), Liszt (Grand Étude de Concert pour les deux mains, les bras, les épaules, le dos, et la chevelure). Vol. 2: Franck (Prélude Solennel), Schumann (Frühstück), J. S. Bach (Choralvorspiel Schneeweiss war sein Vliess), Brahms (Lambsody no. 1), R. Strauss (The Superlamb Tone Poem, freely after Mother Goose), Puccini (Aria: Maria Aveva from Mlle. Agneau), Stravinsky (Sonata in less than one movement), Gershwin (Lamb in Blue), J. Strauss (Waltz Gesang, Mädchen, und Lamm), Sousa (Mary and the Lamb Forever). Need more be said? Questions and Topics 1. Discuss some procedures available to the composer of theme and variations. 2. Thematic variation in improvised jazz. 3. Theme and variations: its prehistory. IM – Part 4 | 6 IV-5. MINUET AND TRIO Objectives This section explains the minuet-trio-minuet form and the internal structure of these larger sections. The Beethovenian transformation of this dance movement into the scherzo is considered, and the section ends with a discussion of and Listening Outline for the minuet from Mozart’s Eine kleine Nachtmusik. Discussion Topics See also the comments on dance and its importance, II-2.16) 1. The text states “the minuet was a stately, dignified dance in which the dancing couple exchanged curtsies and bows.” Perhaps visions of a room full of ornately dressed gentlemen and ladies bowing and scraping in three-quarter time fills the head of the student, with even a vague recollection that the Father of our Country was known to have danced the minuet. A few minutes spent in correcting these misconceptions may well give a better appreciation for the importance of dancing, the reason for the minuet’s inclusion in symphonic forms even after it lost its popularity as a dance, and the period as a whole. It is impossible to have a feeling of baroque and classical style without some appreciation for the importance of the dance. For an interesting and insightful introduction, see Catherine Turocy’s The Pleasures of the Dance: A delightful Journey into the Baroque of 18th Century France (Jarvis Conservatory Master Series, Napa California, 29 minutes). Further information and practical suggestions may be found in Wendy Hilton’s Dance of Court & Theater (Princeton Book Publishers, 1981). Even selected readings will bring rewarding insights and pleasures to anyone exploring the subject, and the minuet figures quite prominently. For dance in America, see “If the Company can do it!” Technique in Eighteenth-Century American Social Dance by Kate Van Winkle Keller (The Hendrickson Group, P. O. Box 766, Sandy Hook, CT 06482-0766). Consider also the two-volume Introduction to Baroque Dance mentioned in III-12 above, which has costumed dancers reconstructing social and theatrical dances from Feuillet’s Chorégraphie (1700). The minuet was a product of the court of Louis XIV, and reflects its stylization and refinement. Classical ballet today is an outgrowth of that court, and the five basic positions were first outlined by Louis’s dancing master. The minuet was normally danced by one couple, while the others observed, flirted, or carried on conversations. The couple would first bow/curtsy to the presence (Louis, or the highest ranking nobleman present) and then to each other. They would then commence an intricate series of steps, tracing patterns with their feet on the floor that would frequently cover the full dancing area. The giving of hands while turning gracefully, and the beautifully embellished “Z” figures can make this a most sensuous dance, far from the common misperception. Steps were small, and the movements clear and economical, full of dignity and poise. The pattern consisted of four steps in six beats, or two measures of music (an important point for conductors and performers to remember so that the music does not become a One-2-3 waltz). The couple would end facing the presence, and pay their respects again. 2. To give some feeling of the difficulty of this dance, have the class execute some of the simpler movements. Since the five positions are basic to the dance and ballet, begin with them. One can usually find a student with ballet experience to demonstrate and instruct the class in each position (descriptions and illustrations of the hand and foot positions may be found in Gail IM – Part 4 | 7 Grant’s Technical Manual and Dictionary of Classical Ballet, an inexpensive Dover edition, as well as other ballet reference books). Ask the class to stand comfortably in place (just notice the usual mixture of bad postures!). Now assume the first position (heels together, feet in a straight line for trained dancers, at a 45 degree angle for others), with chest and head up, stomach in (not so easy for some of us!), full of poise, dignity, and noble bearing. Assume that we are dressed in a beautifully ornamented costume, tightly laced or corseted for the ladies and quite heavy for the men. Men would also be expected to have a hat, usually quite ornate and quite heavy. Now try doing a demi-plié (bend the knees without lifting the heels off the ground, keeping the knees over the toes) followed by a relevé (rise up fully onto the toes, keeping the weight between the big toe and second toe, ankles straight and strong) a few times gracefully. One will begin to understand why the dancing master and daily practice were so important, and why, as with ballet dancers today, it took years of practice to become a good dancer. Following the five positions, teach the students how to bow and curtsy to each other and the presence (the instructor?). The “curtsy” by the ladies consisted of a demi-plié. Illustrations of the bow and hand gestures may be found in Hilton’s book, and in Pierre Rameau’s The Dancing Master. Note especially figure 20, “The King’s Grand Ball,” which illustrates the dance environment described above. Some intricate patterns are illustrated in E. Pemberton’s An Essay for the Improvement of Dancing (both works are available in modern reprints, and your library most likely has them in its dance collection). Musical examples may easily be found in the works of Jean-Philippe Rameau (no relation to Pierre). MHS 4002, besides a pair of minuets from his Les Indes Galantes, contains examples of other dance types of the period. A cassette of four minuets taken from American sources and suitable for dancing, with suggested routines, is available from the Hendrickson Group. A recording mentioned previously (Section II-2 above), French Dances of the Renaissance (Nonesuch H-71036) also contains what Joshua Rifkin calls the perfect model of the “classical” minuet, a work by A. J. Exaudet. This recording is also interesting because the minuet is performed in a period arrangement for viola d’amore and harpsichord, illustrating the sound of that once-popular instrument. 3. Unfortunately, many teachers will feel embarrassed about the above suggestions, and will go directly to the minuet from Mozart’s Eine kleine Nachtmusik. A Listening Outline is available in the text, and of course the form should be discussed before playing. Note that the minuet by this time is no longer intended for dancing, but rather for pleasant listening, as befits a serenade (2:03). Questions and Topics 1. Discuss the character and origins of the minuet as a dance. 2. Explain the origins of the term “trio.” 3. Is the minuet from Mozart’s Eine kleine Nachtmusik still danceable? 4. Diagram the general and internal structures of the minuet movement of the symphony. 5. Beauchamp and the origins of classical ballet. 6. The minuet at the court of Louis XIV. 7. From minuet to scherzo: a study of Beethoven’s third movements. 8. The serenade in the classical period. IM – Part 4 | 8 IV-6. RONDO Objectives This section explains the characteristics of rondo and sonata-rondo form. A Listening Outline is provided for the fourth movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet in C minor, Op. 18, no. 4. Discussion Topics 1. Another means of solving the artistic problem of achieving variety and yet maintaining unity, the rondo is an important form worthy of discussion. The text uses for its example the last movement of Beethoven’s Op. 18, no. 4 to focus on the medium of the string quartet at the same time. If multiple copies of the score are available, they could be used in class, with the Listening Outline used for home study. Both the medium of the string quartet and the form of the rondo should be discussed and illustrated (4:08). 2. You may wish to include the rondo of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in G minor, Op. 13 (Pathétique) in your discussion, since it is contained in the basic set (3:46). A discussion of the first movement of the sonata may be found in Section IV-12 below, and the complete sonata is discussed in the sixth and seventh editions of the text. 3. If you wish to cover sonata-rondo form, consider the third movement of Haydn’s Trumpet Concerto (4:35), discussed in IV-10 below. 4. Chamber music is discussed in IV-9 below, but it would be helpful to the students to discuss the string quartet at this time. Questions and Topics 1. Describe the principle that underlies rondo form. 2. Diagram two variants of rondo form. 3. Explain sonata-rondo form. 4. The rondeau of the French clavecinists: precursor of the classical rondo? 5. The independent rondos of Mozart and Beethoven. IV-7. THE CLASSICAL SYMPHONY Objectives The importance of the symphony as the great contribution of the classical period is explained. The symphonic output of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven is surveyed, and the characteristic content of each of the four movements of the classical symphony explored. IM – Part 4 | 9 Discussion Topics 1. The basic component parts of the symphony have been discussed in earlier sections: sonata form, theme and variations, minuet and trio, and rondo. It is now time to put all the “trees” into the “forest” and show their context in a complete work. You may wish to cover this material very quickly and go on to the next section, perhaps give a short quiz on the materials covered so far in the classical period, or review the various component parts at this time. 2. If you wish additional materials for discussion, note that the recordings contain not only the works discussed so far (Haydn’s Surprise Symphony, Beethoven’s Op. 18, no. 4, Mozart’s G minor and kleine Nachtmusik), but the complete Mozart G Minor and Beethoven Fifth Symphonies. The Online Learning Center contains the remaining movements of Haydn’s Surprise and Dvořák’s New World symphonies. 3. Should you wish to discuss a symphony not covered in the text, please note there is a research project for this purpose in the workbook. This would be particularly appropriate, for example, in preparing the students for a live performance they may be expected to attend. Questions and Topics 1. Describe the characteristic formal plans and content usually found in a classical symphony. 2. Explain how the various movements of a symphony are unified and complemented. 3. Origins of the classical symphony. 4. Haydn’s early symphonies. 5. The significance of the Mannheim school in the development of the symphony. 6. Mozart’s early symphonies. IV-8. THE CLASSICAL CONCERTO Objectives The importance of the concerto in the classical era is explained and its dramatic nature defined. The classical concerto’s three-movement form and double exposition in the first movement are discussed, and this procedure is contrasted with the standard sonata form. The nature and role of the cadenza are also treated. Discussion Topics l. This section is designed as a brief introduction to the classical concerto. Because the prehistory of the classical concerto has been adequately delineated by previous studies of the baroque concerto grosso and solo concerto, further study of the classical concerto may be deferred until Section IV-10 below, where Haydn’s Trumpet Concerto is discussed, or IV-11, where Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23 is discussed. 2. You may wish to explore the form of the double exposition before moving on. The first movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23, discussed in Section IV-11 below, is a fine IM – Part 4 | 10 example. After discussion, see if the students can recognize variations: Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto begins with a brief statement of the theme by the piano soloist, after which the orchestra takes over and presents the material of the first exposition. Beethoven’s Fifth (Emperor) Concerto begins with an extended cadenza for the pianist with chordal punctuation by the orchestra before the orchestra presents the first exposition. Play both opening sections and see if your class can spot these obvious departures from normal procedure in a classical concerto. What effect must these openings have had at the first performance of the works? How is the sense of improvisation generated in the opening of the Emperor concerto? Questions and Topics 1. Define the roles of soloist and orchestra in a classical concerto. 2. Define the nature and function of the cadenza in a classical concerto. 3. Compare and contrast the first movements of a classical concerto and symphony. 4. Concertos for solo brass and woodwind instruments in the classical period. 5. The cadenza in the classical period: notated or improvised? IV-9. CLASSICAL CHAMBER MUSIC Objectives Chamber music is defined in this section as music written for two to nine musicians, with one player to a part. The intimate character of chamber music is stressed, and the problems in playing small ensemble music explained. The string quartet is singled out for special consideration, although other common combinations are mentioned. Discussion Topics 1. The text describes how chamber music during the classical period was often played by well-to-do amateurs or by professional musicians hired to entertain guests after dinner. Have these traditions been entirely lost? Have your students heard any music for small ensembles under these circumstances? A string quartet at a wedding, perhaps? Have they ever sat in on a jam session? 2. The rondo from Beethoven’s String Quartet in C minor, Op. 18, no. 4, was studied in Section IV-6 above. Some time should be given to the importance of the string quartet in the development of chamber music, and the reasons for its preeminence as the major form in the genre. One can cite the sheer number and quality of quartets by the masters, such as Haydn’s 68, Beethoven’s 16, and the many quartets by Mozart, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Dvořák, Bartók, Shostakovich, and others. The supplementary set includes the first movement of Beethoven’s Op. 18, no. 1 quartet, which could be compared with one of his later quartets, such as Op. 130 or the Grosse Fugue. 3. Discuss and provide examples of other standard forms of chamber music, including woodwind and brass combinations. Chamber music for a group of instruments with piano could well be placed in its own special category, since the piano is generally pitted against the other IM – Part 4 | 11 members of the ensemble. Compare, for example, the Beethoven quartet movement with Schubert’s Trout Quintet (fourth movement in the basic set) to note the role of the piano when linked with a few other instruments in a chamber music setting. Consider the piano trio, quartet, and quintet combinations. Contrast the two versions of Beethoven’s Opus 16, the original quintet for piano and winds, and the arrangement for piano and strings. Questions and Topics 1. Discuss the composition of the classical string quartet. 2. Discuss the nature of chamber music and its performance problems. 3. Is chamber music in the home a lost tradition? 4. Discuss the social milieu in which chamber music was performed in the classical period. 5. Haydn’s early string quartets: the divertimento. 6. The piano quartet in the classical period. 7. The violin and piano sonatas of Mozart and Beethoven: a comparison. 8. The development of the wind quintet in the classical period. 9. Harmoniemusik in the classical period. IV-10. JOSEPH HAYDN Objectives Haydn’s career is traced from his birth in the Austrian village of Rohrau, through his early childhood years, to his service at Esterháza and his two triumphant visits to London. The features of his musical style are analyzed, and his enormous output surveyed. The section ends with a description of the third movement, sonata-rondo, of his Trumpet Concerto in Eb Major. Discussion Topics 1. Some of Haydn’s biographical details were discussed in relation to the status of the composer and musician to the aristocracy and the middle class musical environment, and this would be a good time for review (reference was made to “Haydn’s Duties in the Service of Prince Esterházy,” MWW 81, in Section IV-2 above). The workbook has a page to help with the biographical details. 2. Linda Fairtile (New York Library for the Performing Arts) recommends the video Haydn and the Esterházys which “gives a good sense of life as an Esterházy musician, and includes a nice variety of Haydn’s music” (Man & Music, FfH&S ANE1765, 53 minutes, color). 3. Following some brief discussion of Haydn’s place in the development of music, some examples of his music should be given, though it is difficult to make choices out of such an enormous wealth of compositions. Since the sets and Online Line Center have the other three movements of the Surprise Symphony, this may be a good time to present the complete work. The first and second movements are in the basic set (8:28, 6:14), and the third and fourth are included in the Online Learning Center (4:51, 4:07). This will not only review the theme-andIM – Part 4 | 12 variations movement, but place it in context and provide a complete example of a classical symphony (see sixth or seventh edition for a detailed discussion of the symphony). 4. Since so many of Haydn’s works have nicknames, the workbook asks the student to investigate some factors that caused such associations, and you may wish to go over some famous ones in class. 5. Since the text stresses the importance of Haydn’s sixty-eight authentic string quartets and his historical position as (possibly) the innovator of the form, it seems appropriate to discuss some major works in this genre. You may wish, for example, to compare the variations movement of the Emperor quartet (Op. 76, No. 3) with the variations movement of the Surprise Symphony discussed under Section IV-4 above. Considering the text’s reference to the “folk flavor” in many of Haydn’s themes, how do they compare to the melody God Save the Emperor used in the quartet? 6. In discussing the classical orchestra (IV-1 above), the text states “horns and trumpets brought power to loud passages and filled out the harmony, but they did not usually play the main melody.” Reminding the students of the limitations to the overtone series of the natural horns and trumpets, review some orchestral works played in class, or have the students sing a familiar bugle call such as Taps. With this background they can then appreciate the great technical improvement introduced by Anton Weidinger, Prince Esterházy’s court trumpeter, for whom Haydn wrote his concerto. The change from a simple “filler” role to one of being able to play a sustained melody was unprecedented. The work is played today on the modern valve trumpet, and has achieved new notoriety with Wynton Marsalis’s recording (basic set, 4:35). While not the first to win awards for both classical and jazz recordings, he is more relevant to most of the students, and a few moments exploring his background before playing the movement might be in order. From a musical family, Marsalis did not begin serious study of the trumpet until he was twelve. As he stated, he wanted to prove a point: that black artists could succeed in fields other than jazz and rock. Performing solos with the New Orleans Philharmonic (his hometown) at the age of fourteen and sixteen, he later studied at Juilliard. A brief selection from one of his jazz records could be used to stimulate student interest before introducing the Haydn, just as, in days past, teachers played recordings of Benny Goodman’s swing before discussing his recording of the Mozart Clarinet Concerto. Questions and Topics 1. Describe the elements of Haydn’s musical style. 2. Discuss the advantages and disadvantages to Haydn from his employment at Esterháza. 3. Folk song and peasant dance in the music of Haydn. 4. Haydn’s London triumphs. 5. The wind music of Haydn. 6. Haydn’s operas and masses. 7. Haydn and the string quartet: the development of a form. 8. Explore why many of Haydn’s works have nicknames. IM – Part 4 | 13 IV-11. WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART Objectives This section surveys Mozart’s career from the prodigious early years, through the unhappy Salzburg period, to the final tragedy in Vienna. Mozart’s style and his enormous output in all the major forms are described. The section concludes with a detailed discussion of three representative examples of his output, an opera, a symphony, and a concerto. From Don Giovanni there are discussions of the opening scene and the Catalog Aria from Act I, complete with recitative, annotations, Italian libretto, and English translations. The complete Symphony no. 40 in G minor, K. 550, is discussed (a Listening Outline for the first movement was included in section IV-3 above). The first movement of the Piano Concerto No. 23 in A Major, K. 488, is discussed, and a Listening Outline provided. Discussion Topics 1. Where does one start with Mozart? The whole semester could be spent on this man’s work alone, and yet in an introductory course that is neither possible nor practical. The text has singled out three major works as representative, but you may wish to add your personal favorites and leave the text discussions for the students to do as additional listening at home. In any case, certainly some biographical details of this troubled giant should be discussed (the workbook has a page for this purpose). Someone once defined “genius” as a child with a grandmother. You might spend a few minutes discussing why Mozart is generally considered an incomparable genius. Consider comparing his first symphony (K. 16), written at the age of nine (reminding students to envision nine-year-olds they know), with his 40th. Since the slow movement of the first symphony uses the same theme as the finale of the Jupiter symphony, this may be an even more valuable comparison. 2. For background on this period, consider Mozart: Dropping the Patron which “follows Mozart’s career, analyzes his skill at integrating music, drama, and social comedy, explains the role of the piano in his career, and culminates in The Marriage of Figaro, the pinnacle of his success.” The video also includes sections of the Wind Serenade in Eb, the Violin Sonata in G, the Piano Concerto in E Flat, and the String Quartet in Bb (Hunt) (Man & Music, FfH&S ANE1773, 53 minutes, color). 3. In view of the text’s anecdote concerning its mysterious commissioning, you may wish to include some excerpts from the Requiem. The opening section, with its elaborate double fugue, can illustrate the text’s comments regarding Bach’s influence on the mature Mozart. With a view to the coming stylistic period, you may wish to consider the Dies irae and Tuba mirum sections. A comparison of Mozart’s setting with either Berlioz’s or Verdi’s settings of the same text will clearly demonstrate differences between the classical and romantic viewpoints. The Dies irae is included in the basic set (1:44). 4. Remember that several audio/visual clips from Don Giovanni are included on the Online Learning Center. You can also find an audio/visual clip included in the brief set. 5. Depending on the amount of material covered previously in discussing baroque opera, the student should be made aware of the importance of opera in the classical period. Don Giovanni can then be introduced, and the excerpts played in class. If Italian pronunciation was not reviewed previously, the students may need some help at this time. Filmstrips showing the IM – Part 4 | 14 stage settings, scenes, and costumes are available, and would help visualize the plot (both filmstrip and teacher’s guide available from MOG). There are six different videos of the opera available, most with English subtitles. 6. The text states that Mozart’s characters are “individual human beings who think and feel.” You might therefore ask several students to act/read through one of the scenes, analyzing each person’s social position, attitude, and motivation. What is the dramatic function of Leporello’s Catalog aria? How would a female student react to an invitation “to go for a walk” by a handsome wealthy stranger (the latest male sex symbol, for example)? Is Zerlina’s response a human one? What is Don Giovanni’s attitude to life? In his refusal to repent, is it similar to Mussolini’s statement “better to live one hour as a lion, than a hundred years as a lamb”? Much can be done with these few excerpts, and all should be aimed at making the students anxious to see and hear a live performance (the brief set has the Act 1 Introduction, 5:40; the basic set has the Introduction, Catalog aria, 5:48, and the duet Là ci darem la mano, 3:34). 7. The first movement of the G minor symphony was discussed in Section IV-3 above. The text now discusses the complete work. You might consider using multiple copies of the score in the classroom where you can help them keep their place (the brief set has the first movement, 8:12, and the basic set has the complete symphony, 8:20, 7:55, 4:46, and 4:59). A video is available, if you prefer not to use scores. 8. Concerning the popularity of Mozart’s piano concertos, you might mention the recent commercial success of the Theme from Elvira Madigan, which in small print shows it to be the second movement of Mozart’s Piano Concerto in C major, K. 467. 9. The Piano Concerto no. 23 in A major, K. 488, is presented as an example of his great output for solo instrument and orchestra. A Listening Outline is provided for the first movement (basic set, 11:36; the second and third movements in the Online Learning Center, 6:45, 7:59). There is a video available. 10. The first movement of this concerto is performed on a piano, while the second and third feature the fortepiano. This would be a logical place then to compare the two instruments, and to discuss the original instruments movement. 11. If not discussed previously, illustrate the concerto’s double exposition, and discuss the cadenza. Note that in this concerto, Mozart did not leave it for the soloist to extemporize. 12. In this chapter’s Performance Perspective, students read in brief about Murray Perahia’s performing career, including an account of an injury that kept him from performing for several years. You might use this as an opportunity to talk informally with students about the specifics of different careers in music. It is important to humanize those performers and composers who are more typically revered, and students are often interested to hear about how they became the musicians they are, as well as hearing about the day-to-day lifestyle of a pianist, composer, opera singer, etc. Questions and Topics 1. Describe Mozart’s career in Salzburg and Vienna. 2. Discuss the principal influences on the development of Mozart’s musical style. 3. Summarize the libretto of Don Giovanni. 4. Compare and contrast Mozart’s style with that of Haydn. 5. Mozart’s letters. 6. Mozart’s concertos for solo instruments. IM – Part 4 | 15 7. Mozart’s German operas. 8. Mozart and Freemasonry: The Magic Flute. 9. Mozart’s music for winds: the divertimenti, cassations, and serenades. IV-12. LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Objectives This section opens with a discussion of Beethoven’s childhood, his early musical training, and the triumphant early years in Vienna. The deterioration of his hearing and the effect of this affliction on his career is also treated. Beethoven’s style, style periods, and his enormous effect on the history of music are described. Two works are discussed in detail: the first movement of the Piano Sonata in C minor, Op. 13 (Pathétique), and the complete Fifth Symphony. A Listening Outline is provided for the first movement of the symphony. Discussion Topics 1. The text quietly begins “For many people, Ludwig van Beethoven represents the highest level of musical genius.” Can we imagine the course of musical history without Beethoven? What would be the reputations today of Hummel, Clementi, and Pleyel, among others, had there been no Beethoven? As with Mozart, where can one begin? The text and recordings limit themselves to but four masterpieces: the Pathétique Sonata, the C minor symphony, and movements from two string quartets. Again you may wish to include your own favorites, leaving these four works for the students to study at home, since Listening Outlines are provided. Again, a page is provided in the workbook to help with the biographical details. 2. For a general introduction to Beethoven and his times, consider the videos Beethoven: The Age of Revolution or Beeethoven: The Composer as Hero. The former “chronicles Beethoven’s career, counterpointing it against Napoleon’s moves across the European landscape, culminating in the Eroica.” The latter “covers the works of public idealism, from the Fifth Symphony and Fidelio onwards . . . to the triumphant Ninth Symphony.” (Man & Music, FfH&S ANE1776, ANE1777, each 53 minutes, color.) 3. Consider also the film Beethoven: Ordeal and Triumph (McGraw-Hill, 1967, 52 min.). The work deals with his early personal life, his oncoming deafness, and the Heiligenstadt testament (the complete testament is included in MWW, 91). His triumph over despair is illustrated by the Third Symphony, whose themes had already been presented in the country dance and Prometheus Ballet settings. 4. Remind the students who may have seen Disney’s Fantasia that Beethoven’s sixth symphony was used for one of the sequences. The new Fantasia 2000 contains Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. Both are available on video, and you might wish to discuss some of the other works in the two films. 5. One should not leave the subject of Beethoven without granting the students the opportunity of hearing Schiller’s Ode to Joy and the magnificent Ninth Symphony. The text, with translation, should be duplicated so that the students may understand the poem. You might mention the rock adaptation (?!) of the brotherhood theme issued under the title Song of Joy IM – Part 4 | 16 some years back, in case any of the students may still remember it, and compare it with the original (actually, no comparison!). More important than the rock version, however, is the current movement in Europe where the brotherhood theme is assuming the status of an unofficial anthem. Le Drapeau de l’Europe (The Flag of Europe), by which this hymn is known, expresses the hope for a peaceful, harmonious European community. 6. You might wish to discuss Beethoven’s only opera. Typical of the many nineteenthcentury “rescue” operas, Fidelio amply demonstrates Beethoven’s genius in taking an existing form and raising it to heights never before achieved. A filmstrip is available to set the scene, and perhaps the plot can be illustrated with one or more arias and choruses. There are two videos of the opera available. 7. Beethoven’s string quartets are considered among the greatest in the entire literature, so much so that they simultaneously intimidated and inspired such composers as Schubert, Brahms, and Bartók. The fourth movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet Op. 18, no. 4, composed between 1798 and 1800, was discussed in the section on rondo form (IV-6). That section includes a Listening Outline, and the movement is included in the brief and basic sets (4:08). A comparison of the opus 18 movement with a later quartet such as the opus 130 or opus 133 (Grosse Fugue) would compare his early and late periods and clearly exemplify the text’s statement “the sublime works of the late period often contain fugues as well as passages that sound surprisingly harsh and ‘modern’.” 8. It may be appropriate at this time to take a few moments to discuss the development of the piano and its literature. The harpsichord, the early pianoforte (leather-covered hammers, etc.) and the modern piano should be discussed before introducing the Beethoven sonata. Mention has already been made of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 23 performed on the pianoforte, and it may be compared to the later sounds and effects of the romantic concert grand. Beethoven’s Pathétique Sonata can then be placed in context. The text provides an analysis, and the complete work is included in the basic set (7:16, 4:55, and 4:30). 9. The Fifth Symphony is the example chosen to represent Beethoven’s orchestral output, and Listening Outlines are provided for the first and second movements, with detailed discussions of the third and fourth. The complete symphony is included in the brief and basic sets (7:07, 9:58, 5:08, 8:58). As mentioned before, you may wish to discuss the Listening Outlines quickly in class to prepare the students for home listening, and then use multiple copies of the score in class where you can guide them successfully through it with minimal frustration. There are several fine video performances of the symphony available. 10. If your class is already familiar with the work, you may wish to consider Peter Schickele’s sportscaster analysis of the first movement on his P. D. Q. Bach on the Air (Vanguard VSD-79268). For a different interpretation, see the Walter Murphy Band’s recording A Fifth of Beethoven (PS 2015). Questions and Topics 1. Describe Beethoven’s childhood and early musical training. 2. Describe the sources of Beethoven’s income during his Viennese period. 3. Describe the manner in which Beethoven unified the contrasting movements in his works. 4. Describe those elements of Beethoven’s style that contribute to the dramatic intensity of his music. IM – Part 4 | 17 5. Divide Beethoven’s output into periods, and define the characteristics of each phase. 6. The Heiligenstadt testament: triumph of genius? 7. Fidelio: opera or staged oratorio? 8. Beethoven the romanticist. Suggested Supplements for Part IV Many resources have been mentioned above. Below is a brief list of additional supplements you may wish to consult, all currently available on DVD or VHS. Mozart - Don Giovanni, Maazel, Raimondi, Te Kanawa, Paris Opera (Columbia Tristar) Mozart - Don Giovanni, Allen, Gruberova, Murray, Araiza, Desderi, Mentzer, Muti, La Scala Opera (Naxos) Beethoven - Symphonies 2 and 5, Claudio Abbado, Berlin Philharmonic (Naxos) IM – Part 4 | 18 IM – Part 4 | 19