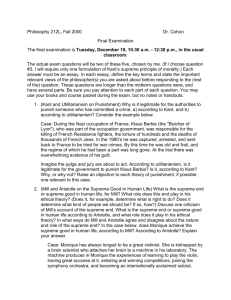

Essay (Kant and Mill)

advertisement

Clay Chastain 1 Clay Chastain Dr. Heil Philosophy 1354-2 12 February 2007 On Kant and Mill’s Ethics In both Immanuel Kant’s Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals and John Stuart Mill’s Utilitarianism, the authors give several strong, well structured arguments on the composition of ethics. Largely, their works help to draw focus to two different explanations of what makes an action morally just as opposed to morally unjust through essentially opposite viewpoints. Despite a key difference between their philosophies, Kant and Mill contribute to an overall picture of the historical ethical argument. Chronologically, the first major philosopher, Immanuel Kant, presents an argument that is based upon solely “a priori” knowledge, or rather knowledge that does not come from experience. Kant explains that because we are all rational beings, we are able to separate ourselves from our current human condition and use our own ability to reason to see a broad picture of what is morally acceptable to others. Similarly, Kant finds that the only thing which is good without limitation is a good will; that is, it is the intention of an action that determines the moral validity of any claim, not the effects both foreseen and actual. Kant connects this idea of morality to the claim that humans should act out of duty instead of just what is according to duty. The difference between these two ideas, Kant argues, is that “according to duty” is acting in the right way only because of the negative consequences associated with not performing a morally correct action whereas “from duty” refers to the concept of doing something solely because it is the Clay Chastain 2 right choice to make in a given situation. Rephrased, Kant calls these two choices the categorical imperative (from duty), which is completely unconditional in its call for action, and the hypothetical imperative (according to duty), which has one or more conditions that have to be satisfied for an action to be initiated. Further elaborating on this subject, Kant postulates two different forms of the categorical imperative; the first says that one should only act in accordance with a maxim that he or she wills to be a universal law (often known as the concept of universalization), while the second states that others should be treated only as an end, not merely as a means to an end. Overall, both of these versions of the categorical imperative state a similar message in that they basically add up to be a modified version of the Golden Rule. That is, “one should act onto others as anyone would do as anyone would do onto oneself” (Lecture 1/23 to 1/30). In practice, many of Kant’s ideas can be easily applied to real world situations; however, in contrast, a variety of situations arise where his theories can be jeopardized. For instance, the concept of a good intention can be explained without much difficulty. Suppose that you are walking in the city, and you see a child in front of a speeding bus. Your intention is to push the child out of the way of the bus, but even though you tried to save his or her life, you were not fast enough. Despite this, it was your intention that was pure, even though you could not help the child in time and the effects were definitely negative. However, when conflicts of values arise, Kant’s theory is put the test. Suppose this time that you are a German home owner in World War II, and you are keeping a Jewish refugee in your basement until he or she can make it to safety. A Nazi officer comes to your door and asks you if you have any Jewish people in your house (Kania Clay Chastain 3 Lecture, Fall 06). If you choose to lie to the officer, you are not acting upon the categorical imperative because you are taking conditions into account before deciding which action is the worthier of the two. However, both choices clearly have moral worth: one is doing the right thing by not lying, whereas the other option is to lie and protect the Jewish refugee. This brings up the question of performing a duty (being honest to the Nazi officer) and in turn producing mass unhappiness (the harm of a Jewish refugee). In this way, Kant’s theory is put to the test because the consequences of the action seem to determine what the correct choice in this situation is. Another problem with Kant’s theory arises in the power of the concept of universalization. For example, if a bully says that he or she wills the act of bullying to be universal, this could bring justification to the torturing other people. In this way, the theory appears to wane, but a common response to this that one must sincerely agree to what he or she wills. Simply put, the bully must picture a stronger adversary than he or she is and then consent to the terms of the universalization. One other example of a problem in the application of Kant’s theory arises in trying to gauge the moral “worth” of an action done out of the right feelings as opposed to the wrong feelings. Kant’s views are that all moral choices are equal as long as the intention is good. Yet, dreading doing something good and still doing it generally appears to be less morally worthy than doing something good because it is the right thing to do. However, the opposite could easily be said because it takes more maturity to do the dreaded action than doing something that you take pleasure in, so the verdict is still out on which is more worthy, or if there is even a difference in worth (Lecture, 1/32, 2/07). Clay Chastain 4 On the opposite side of the moral theory spectrum, John Stuart Mill’s concepts work on the basis of “a posteriori” knowledge, which is knowledge that comes solely from experience – a direct opposite of Kant’s line of thinking. Mill believes strongly in judging an action based upon its effects (commonly referred to as consequentialism). Through this line of thinking, Mill came upon a major contribution to the field of ethics, which is often simplified into the idea of utilitarianism, which is the concept of doing the greatest amount of good for the greatest amount of people. Mill also uses an idea called the greatest happiness principle; this rule ties the idea of doing good things for people to being equal to bringing happiness to people. Simply put, by doing the greatest amount of good for the greatest amount of people, you are in turn also creating the greatest amount of happiness through your good actions (Lecture, 1/30 – 2/01). Although Mill’s ideas are more directly stated than those of Kant’s, they contain the same ability to be applied to everyday situations. For example, suppose that you have the ability to save a small child from being hit by a speeding bus, or keep a promise to a friend. Where Kant’s theory has a problem with conflicting moral obligations, Mill’s theory is clear in its execution: save the small child from impending death because it would obviously give the greatest amount of happiness to society. Yet, just the same as Kant, Mill’s ideas also have certain flaws which can become apparent when examined closely. The first of the major flaws is in how happiness is actually measured. Mill’s own teacher, Jeremy Bentham, believed in an idea of a quantitative way to determine happiness via the use of scientific measuring devices, which was referred to as the “calculus of felicity” (Mike Fisk, University of Michigan Student). However, Mill Clay Chastain 5 rejected this idea and believes that there are clear qualitative differences between the different types of pleasures. Namely, he finds that spiritual pleasures are indeed stronger than more basic pleasures in life, so we obviously seek them out in our lives to achieve a higher level of pleasure. Unfortunately, this raises the question of determining if spiritual pleasures really are greater than physical pleasures; Mill’s belief is that to determine which is greater, a person must ultimately have a full and complete experience of both types of pleasures, and after which, the person will pick the higher pleasures. Of course, this situation does not exist in real life to the ideal extent that Mill stresses, so many people may gauge physical pleasures as greater. Further, even if one could achieve a full knowledge of both forms of pleasures, there is no proof to say that the preference is generally fickle and completely up to the mind of different people to rank. Another critical question raised from Mill’s moral theory is how it is possible to calculate the consequences of an action beforehand. Sadly, as humans do not have knowledge of the future, no one can ever hope to know the result of a situation, so choosing an action based upon past experience cannot guarantee that it will indeed be the correct action to take. This problem is often referred to as act utilitarianism, which is knowing what an action will actually cause. Mill’s response to this criticism that we know basically what will happen from our past experiences to a reasonable degree, which is known as rule utilitarianism. A simple example of this is asking a person for the time, and the person responds with the time as expected. We can generally know that the person will give us a reasonable answer due to our past experiences at asking the time from other people or being asked for the time. Similarly, in other situations, we can make generalizations which are just that: an action that will generally produce certain results. Clay Chastain 6 Following the idea of doing the greatest amount of good for the greatest amount of people, it would seem that this idea encourages stifling the least amount of people. Logically, if you cater to those in the majority by doing good to them only, you would be neglecting the minority. Mill argues that problem’s logic (often known as the Justice Problem) is absolutely not the case; in fact, he feels that neglecting a minority is counterproductive to the happiness of the many. His reasoning follows the line of understanding that the focus of power in a society can shift rapidly, so the minority must be supported in case the majority one day becomes the minority. One last criticism of Mill comes from a point raised by Bernard Williams: our own personal values often will supersede those standards of morality put in place by Mill’s theories. Williams’ example is that you have the choice of killing one person to save several other lives, or not doing anything and all of the people will be killed. Williams’ argues that our internal values are often stronger; a person may be extremely opposed to killing any people, even for the sake of the other people who will die without intervention. This sense of values is similar to Kant’s theory about using a person as a means to an end; in this case, Kant would be opposed to Mill’s philosophy in this example. While this is true, because of the variability of values from person to person, a person may opt to kill one person to save the many because he or she personally finds it more respectable to use a utilitarian approach to the situation (Lecture, 2/06 – 2/08). Overall, both Kant and Mill have strong arguments which have greatly impacted the discussion of ethics through the generations. Despite the many claims that both viewpoints have certain weak points, these theories have many strengths as well. It is in that light that both theories can be considered roughly equal – where one philosophy Clay Chastain 7 drops off, the other generally picks up. Where there is a conflict, it is ultimately up to the person in a particular situation to use their ability to reason to choose the optimal choice between the competing ideas as no one idea can be totally wrong or totally right.