This paper attempts to demonstrate that the initial rise of Islam in the

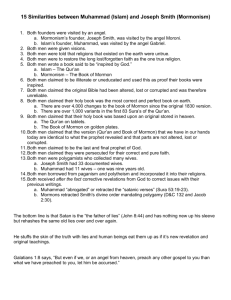

advertisement