Historical Question: Did Malcolm X and Martin Luther King have

advertisement

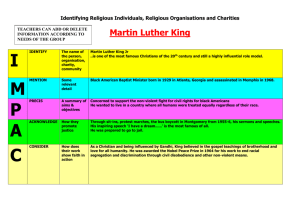

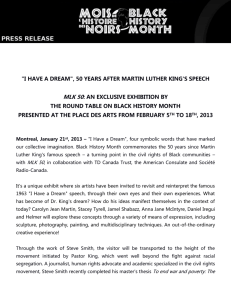

Historical Question: Did Malcolm X and Martin Luther King have radically different views of equality? Author: Megan Perry School: Edith E. Mackrille District: West Haven Overview: Malcolm X and Martin Luther King both wanted equality for African Americans. The two men went about getting this issue addressed in two different manners. By the time the students finish working with the 6 primary documents they will be able to compare and contrast the ways Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X felt about equality. The students will be able to see how each man wanted the same rights for their people, but they went about it in different ways. The students will also be able to learn that while the men had different approaches to obtaining equality they shared a common respect for one another. Document Summary: Document 1 shows how Malcolm X was reaching out to Martin Luther King Jr. to attend a rally. While Malcolm X did not believe in the non-violent approach that Martin Luther King took he did believe that there should be equality for all men and women of all races. He wanted to show the people that even though their ideas about getting equality were different the two men could attend and work together. Document 2 shows a quote taken from Martin Luther King Jr’s book. The quote is telling people of all races and religions and genders that no matter we need stand up and stand together to gain equality. We must do this in a non violent manner. Document 3 is a selection of quotes from Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. The students can use these quotes to see how the man felt about civil rights and equality for African Americans. These quotes allow the students to see the similarities and differences between the two men. The children will be to compare and contrast the views each man had on equality. Document 4 shows how people felt about Martin Luther King Jr. It also shows how his peaceful and non violent measures to make changes did have a great impact. The students can use this to compare the way Martin Luther King Jr. handle the equality issues against the way Malcolm X handled them. It will also give the students a look as to see how others perceived him. Document 5 shows the two views of both men on equality. The students can use this article to compare the two men views. It shows how Malcolm X believes that African Americans should have a handle in their own business and that a non violence approach does not always work. It shows Martin Luther King Jr.’s view on how to solve the issues using peaceful means. Document 6 shows how Malcolm X felt about Martin Luther King. The student’s can use this to compare the ways that Malcolm X started to change his ways on getting the nation to equality. Procedure (80 minutes): 1. Introduction of lesson, objectives, overview of SAC procedure (15 minutes) 2. SAC group assignments (30 minutes) a. Assign groups of four and assign arguments to each team of two. b. In each group, teams read and examine the Document Packet c. Each student completes the Preparation part of the Capture Sheet (#2), and works with their partner to prepare their argument using supporting evidence. d. Students should summarize your argument in #3. 3. Position Presentation (10 minutes) a. Team 1 presents their position using supporting evidence recorded and summarized on the Preparation part of the Capture Sheet (#2 & #3) on the Preparation matrix. Team 2 records Team 1’s argument in #4. b. Team 2 restates Team 1’s position to their satisfaction. c. Team 2 asks clarifying questions and records Team 1’s answers. d. Team 2 presents their position using supporting evidence recorded and summarized on the Preparation part of the Capture Sheet (#2 & #3) on the Preparation matrix. Team 1 records Team 2’s argument in #4. e. Team 1 restates Team 2’s position to their satisfaction. f. Team 1 asks clarifying questions and records Team 2’s answers. 4. Consensus Building (10 minutes) a. Team 1 and 2 put their roles aside. b. Teams discuss ideas that have been presented, and figure out where they can agree or where they have differences about the historical question 5. Closing the lesson (15 minutes) a. Whole-group Discussion b. Make connection to unit c. Assessment (suggested writing activity addressing the question) Document 1 This was a letter that Malcolm X wrote to Martin Luther King Jr asking him to attend a rally. Malcolm X is basically saying that there is no reason why the 2 men cannot get along. They both want equality, even though there ways of going about it are completely different. Vocabulary Capitalistic-favoring or practicing capitalism Communistic-relating to or marked by communism; "Communist Party"; "communist governments"; "communistic propaganda" Ideological-of or pertaining to or characteristic of an orientation that characterizes the thinking of a group or nation Source: http://www.stanford.edu/group/King/liberation_curriculum/pdfs/letter_malcolmxtoking.pdf Document 2 This quote taken from Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. This quote is basically telling the people that they were promised freedom, but they are not as free as the whites and that hopefully one day we will all be equally free. I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation. Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of captivity. But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. So we have come here today to dramatize an shameful condition. In a sense we've come to our nation's Capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check; a check which has come back marked "insufficient funds." But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. So we have come to cash this check- a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice. We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksand of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children. It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges. But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone. And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall march ahead. We cannot turn back. There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, "When will you be satisfied?" We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating "for whites only." We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream. I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair. I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: "We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal." I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood. I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice. I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today. I have a dream that one day down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of interposition and nullification, that one day right down in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today. I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight, and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together. This is our hope. This is the faith that I will go back to the South with. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day. This will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning, "My country 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrims' pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring." And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true. So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire. Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York. Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania. Let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado. Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California. But not only that; let freedom ring from the Stone Mountain of Georgia. Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee. Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi. From every mountainside, let freedom ring. And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, "Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!" Vocabulary Manacles- either of a pair of metal rings joined by a chain and fastened around the wrists of a prisoner to be restrained Segregation- the practice of keeping ethnic, racial, religious, or gender groups separate, especially by enforcing the use of separate schools, transportation, housing, and other facilities, and usually discriminating against a minority group Prosperity- the condition of enjoying wealth, success, or good fortune Languished- to undergo hardship as a result of being deprived of something, typically attention, independence, or freedom Architects- somebody who creates or invents something promissory note- concerning, containing, or implying a promise defaulted- a failure to meet an obligation, especially a financial one insufficient funds- not enough in amount or quality to satisfy a purpose or standard hallowed- buried in hallowed ground tranquilizing- become calm gradualism- the principle, theory, or policy of allowing change, especially political change, to take place gradually rather than suddenly or drastically sweltering - oppressively hot whirlwinds- something that happens very quickly, or a rapid succession of events revolt- a protest against authority or rules degenerate- to develop into a condition that is worse than before, worse than normal, or not as good as it should be inextricably- hopelessly involved or complex tribulations- a problem, or a difficult persecution- the subjecting of a race or group of people to cruel or unfair treatment, e.g. because of their ethnic origin or religious beliefs redemptive- bringing about the redemption of somebody or something interposition- to intervene or interfere in a situation such as a dispute nullification- the act of making something Source: From Revolution to Reconstruction Document 3 This document is a selection of quotes taken from both Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. In the quotes you are able to see how both civil right leaders wanted freedom for their people and for all. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X: A Common Solution? Quotes Handout Martin Luther King, Jr. Quotes “I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today – my own government.” —King, 1967 “I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values.” —King, 1967 "There is a magnificent new militancy within the Negro community all across this nation. And I welcome this as a marvelous development. The Negro of America is saying he's determined to be free and he is militant enough to stand up." —King, 1963 ”Don't let anybody frighten you. We are not afraid of what we are doing... We, the disinherited of this land, we who have been oppressed so long, are tired of going through the long night of captivity.” —King, 1955 “Black men have slammed the door shut on a past of deadening passivity.” —King, 1968 Malcolm X quotes “You can't separate peace from freedom because no one can be at peace unless he has his freedom.” —Malcolm X, 1965 “We can never get civil rights in America until our human rights are first restored. We will never be recognized as citizens until we are first recognized as humans.” —Malcolm X, 1964 “I believe in human beings, and that all human beings should be respected as such, regardless of their color.” —Malcolm X, 1965 “It is a disgrace for Negro leaders not to be able to submerge our “minor” differences in order to seek a common solution to a common problem posed by a common enemy.” —Malcolm X, 1963 “I have been convinced that some American whites do want to help cure the rampant racism which is on the path to destroying this country.” —Malcolm X, 1964 Vocabulary Oppressed-to subject a person or a people to a harsh or cruel form of domination Revolution- a dramatic change in ideas or practice Militancy- extremely active in the defense or support of a cause, often to the point of extremism Passivity- passive behavior, or the quality of being passive Source: Taken from Sanford.edu, Liberation Curriculum Document 4 This document is about Martin Luther King’s method of using non-violence as a way to make a statement. The document also talks about Malcolm X and how he disagreed with Martin Luther King’s method and how he felt most African Americans felt the same way that being peaceful and loving your enemy will not help make changes Martin Luther King's creed of non-violence surprised many Americans. Though conceding that King's methods were effective, black psychologist Kenneth Clark called the philosophy of loving one's enemy "psychologically burdensome." In a 1963 interview, Malcolm X accused King of working "to keep Negroes defenseless in the face of an attack." Nevertheless, King's approach achieved success in Montgomery, Alabama, and other civil rights hot spots. Influential Writings "Unjust laws exist; shall we be content to obey them, or shall we endeavor to amend them, and obey them until we have succeeded, or shall we transgress them at once?" -- Henry David Thoreau, "On Civil Disobedience" (1849) Journalist David Halberstam described Martin Luther King as "a black Baptist Brahmin." The son and grandson of Atlanta preachers, King grew up in an environment where much was expected of him -- and he did not disappoint. Young Martin studied at Morehouse College, Crozer Theological Seminary, and Boston University, where he completed a Ph.D. in systematic theology in 1955. During his years of study, King found truths in a long list of writers and books, from Henry David Thoreau and his famous essay, "On Civil Disobedience," to Walter Rauschenbusch's Christianity and the Social Crisis. But perhaps the most important sources of his developing philosophy were the Bible and the writings of Mahatma Gandhi. Christian Teachings "Now it came to pass, when Jeremiah had made an end of speaking all that the Lord had commanded him to speak unto all the people, that the priests and the prophets and all the people took him, saying, Thou shalt surely die." -- Jeremiah 26:8 "In order to understand Martin Luther King," his friend William Gray said, "you must start with the fact that he was a minister." Raised in the Southern black church, King lived, learned, and preached within the Christian cycle of suffering and redemption. "My Bible tells me that Good Friday comes before Easter," he once said, and he would refer to setbacks as the necessary midnights that would precede a dawn of shining equality and justice. King took many lessons from Christian teachings. He studied martyrs like Jeremiah, whom he described as "a shining example of the truth that religion should never sanction the status quo." In the famous letter he wrote from the Birmingham Jail, King said he modeled his actions on those of Christian saints who "left their villages and carried their 'thus saith the Lord' far beyond the boundaries of their hometowns... [as] I am compelled to carry the gospel of freedom beyond my hometown." And in what would be his final speech, in April 1968, he accepted the reality that he could be killed for his actions, saying, "I may not get there with you... but we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land." Perhaps most of all, King relied on New Testament teachings as he developed his philosophy of non-violence and his commitment to social justice. "Love your enemies," King surely read many times in the book of Matthew. "Bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you." Gandhi and India "Nonviolence is the first article of my faith. It is also the last article of my creed." -- Mohandas K. Gandhi, 1922 In spring 1950, at age 21, Martin Luther King heard Dr. Mordecai Johnson, the president of Howard University, deliver a sermon on Gandhi. Intrigued, King began an intensive study of the Indian leader's philosophy. Especially impressed with Gandhi's Salt March to Dandi in 1930, a non-violent act of civil disobedience, King came to understand the Christian teachings of loving one's enemy and turning the other cheek as philosophies that held powerful potential as social forces for positive change. Rosa Parks' arrest in December 1955 for refusing to observe public bus segregation laws provided King's first opportunity to test a non-violent approach. He and other black leaders organized a successful year-long boycott of Montgomery's buses that led to a U.S. Supreme Court case and, ultimately, victory. "The potential and possibilities of non-violence in the movement were beyond anything that we could have ever thought of," recalled civil rights activist Rev. C. T. Vivian. Though King's home was bombed, anonymous phone callers made threats, and King and others were jailed in mass arrests, King steadfastly preached tolerance. "We must use the weapon of love," he told the New York Times. "We must have compassion and understanding for those who hate us." He would explain, in a later interview, "This approach certainly doesn't make the white man feel comfortable. It disturbs his conscience." In 1959, King fulfilled his longtime wish to see India, meeting Gandhi's son and other relatives, and visiting some of the places where Gandhi had lived. The Limits of Non-Violence "Dr. King... I say this. Sure we like to be non-violent but we up here in the Los Angeles area will not turn that other cheek." -- unidentified man after the Watts Riots, Los Angeles, 1965 Martin Luther King's non-violent approach was always a tough sell with some people who were angry at violence against African Americans and intent on protecting themselves or seeking revenge. "The goal of Dr. Martin Luther King is to get Negroes to forgive the people who have brutalized them for 400 years," Malcolm X told an interviewer in 1963. "But the masses of black people in America today don't go for what Martin Luther King is putting down." Whether or not Malcolm X was truly speaking for the masses, the spring 1965 Selma march was a particular turning point, and the Watts riots later that year solidified the refusal of some black Americans to listen to Dr. King. Civil rights lawyer Harris Wofford recalled, "I began hearing a number of the young militants calling him 'the Lord' derisively." In historian Taylor Branch's view, "he was the natural object of people's frustration. That was part of the price he had to pay for the position that he was in." Within a year of the Watts Riots, a group of African Americans in Oakland, California founded the controversial, militant Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. King's Legacy Over thirty-five years after his death, Martin Luther King's legacy lives on. A statue of King decorates the front façade of London's Westminster Abbey, along with statues of nine other 20th century martyrs. Streets and schools across the United States have been renamed after the civil rights leader. And in 1986, President Ronald Reagan declared the third Monday in January a federal holiday in honor of Dr. King. But even more than monuments and holidays, King's legacy is present in worldwide movements for democracy and individual rights. Civil rights leader Andrew Young believes King's "I Have a Dream" speech "made the history not only of the civil rights movement... [but] helped get Nelson Mandela out of jail. It helped bring down the Berlin Wall. It inspired students in China to organize in Tiananmen Square. The shipyard workers in Poland. Everywhere in the world people saw that, and were inspired, and everybody in the world to this day identifies with... Martin Luther King's expression of the American dream." Vocabulary Psychologically- affecting or intended to affect the mind or mental processes Burdensome- difficult or worrying to bear or deal with Disobedience- a refusal or failure to obey Derisively- showing contempt or ridicule Source: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/malcolmx/tguide/index.html Document 5 This statement is two views from Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. Martin Luther King believed in love and peaceful means of getting your points across, the statement then shows Malcolm X’s views of not agreeing with Martin. While both men strived for equality they had two different points of views. You are to use this article to compare their points of view In the 1950s and 60s, African Americans could choose between two radically different strategies for obtaining their civil rights: the Christian-oriented, non-violent tactics advocated by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and the Muslim-based, separatist approach promoted by Malcolm X. King sought integration -- of buses, lunch counters, and society as a whole -- achieved through non-violent action, and he stressed the need to remain peaceful even when confronted by white attacks. In a sermon in 1965, he preached this message: We will match your capacity to inflict suffering with our capacity to endure suffering. We will meet your physical force with soul force. We will not hate you, but we cannot in all good conscience obey your unjust laws. Do to us what you will and we will still love you. King did not consider such non-violence to be either passive or weak, "I think of love as something strong, and that organizes itself into powerful direct action." Malcolm X, by contrast, thought it absurd to seek integration through love with his white oppressors. He sought to create a separate, economically self-sufficient and racially proud nation of blacks within America. Malcolm X expressed it this way: The black man should have a hand in controlling the economy of the so-called Negro community, he should be developing the type of knowledge that will enable him to own and operate the businesses and thereby be able to create employment for his own people, for his own kind. Discussing non-violence, Malcolm X said, [don't mistake black Muslims] "for those Negroes who believe in non-violence," [if you] "put your hands on us thinking that we're going to turn the other cheek -- we'll put you to death just like that." Vocabulary oppressors to subject a person or a people to a harsh or cruel form of domination Source: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/malcolmx/tguide/index.html Document 6 This document shows how Malcolm X felt about Martin Luther King and his views on civil rights. Both men wanted equality but their ways and beliefs varied greatly. Although they only met once, Malcolm X was often asked his opinion of Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement. Initially scornful of King and his strategies, Malcolm later began to recognize the worth of -- and even began tentative participation in -- the movement. Same Problem, Different Directions Near the end of his life, Malcolm X publicly recognized that "Dr. King wants the same thing I want -- freedom!" But for most of his ministry he did not identify with King and the civil rights movement. Although both Black Muslims and King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference had the same general goals of defeating white racism and empowering African Americans, Malcolm and King had different tended to speak at different venues (street corners vs. churches) and had different aims. Malcolm, who would publicly deny that he was even an American, worked for a Nation of Islam that sought to create a separate society for its members. Malcolm rejected integration with white America as a worthwhile aim (deriding it as "coffee with a cracker") and particularly opposed non-violence as a means of attaining it. "That's what you mean by non-violent," he said, "be defenseless." In Malcolm's mind, the African American could never surrender his right of self-defense against white violence. Nothing But Scorn As for the apostle of non-violence, for years Malcolm showed him nothing but scorn. King was a "fool," a modern-day "Uncle Tom," and his march, where King gave his celebrated speech, just a "farce on Washington." The "white man pays Reverend Martin Luther King, subsidizes Reverend Martin Luther King, so that Reverend Martin Luther King can continue to teach the Negroes to be defenseless." And the Christianity that motivated King was "the white man's religion." For his part, civil rights leader Thurgood Marshall called the Nation of Islam "a bunch of thugs organized from prisons and jails and financed, I am sure, by some Arab group." King himself took the higher road, rarely criticizing Malcolm but also refusing to publicly debate him. King would not debate, his secretary told Malcolm, because "he has always considered his work in a positive action framework rather than engaging in consistent negative debate." Changing Times, Changing Notions As time passed, Malcolm X became less confrontational towards King and the rest of the civil rights movement, a shift that came in tandem with his growing estrangement from Elijah Muhammad. To be sure, the Nation of Islam talked a good game, but when Los Angeles Temple secretary Ronald Stokes, originally from Roxbury, was gunned down by police, Muhammad refused to permit an aggressive response, counting on God to avenge the incident. In Malcolm's words, "[Muhammad] is willing to wait for Allah to deal with this devil, [but] the rest of us black Muslims...don't have this gift of divine patience with the devil. The younger black Muslims want to see some action." Meanwhile, King and his followers were scoring a number of social and legislative victories. No Longer Adversaries Bit by bit, Malcolm began a process of engagement with the movement. He went to Washington and witnessed debate on the Civil Rights Bill of 1964, running into King in the process. "I'm throwing myself into the heart of the civil rights struggle," Malcolm said. Where previously his separatism had meant no interest in voting, he now told Mississippi youth that he was with voter registration efforts "one thousand per cent." He accepted an invitation from the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee to speak in Selma, Alabama, and had conciliatory words for Coretta Scott King, whose husband was then in jail. "I want Dr. King to know that I didn't come to Selma to make his job difficult," Malcolm said. "If the white people realize what the alternative is, perhaps they will be more willing to hear Dr. King." While never embracing King's Christianity or his commitment to non-violence, near the end of his life Malcolm X gave indications that he was willing to work with the fellow preacher, that they could be, if not exactly partners, then at least no longer adversaries in the quest for civil rights. Condolences In a telegram to Betty Shabazz after Malcolm's assassination, Martin Luther King Jr. said, "While we did not always see eye-to-eye on methods to solve the race problem, I always had a deep affection for Malcolm and felt he had a great ability to put his finger on the existence and root of the problem. He was an eloquent spokesman for his point of view and no one can honestly doubt that Malcolm had a great concern for the problems we face as a race...." Vocabulary Confrontational- a face-to-face meeting or encounter, especially a challenging or hostile one Tandem- with one behind the other Estrangement-to cause somebody to stop feeling friendly or affectionate toward somebody else or sympathetic toward a tradition or belief Separatism- somebody who breaks away from or who is in favor of breaking away from a group, organization, or country Adversaries- an opponent in a conflict, contest, or debate Source: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/malcolmx/tguide/index.html Some of the language and phrasing in these documents have been modified from the originals. CAPTURE SHEET Did Malcolm X and Martin Luther King have radically different views of equality? Preparation: 1. Highlight your assigned position. Don’t forget the rules of a successful academic controversy! 1. Practice active listening. 2. Challenge ideas, not each other 3. Try your best to understand the other positions 4. Share the floor: each person in a pair MUST have an opportunity to speak 5. No disagreeing until consensusbuilding as a group of four Yes: Malcolm X and Martin Luther King had radically different views of equality. No: No, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King did not have such different views of equality 2. Read through each document searching for support for your side’s argument. Use the documents to fill in the chart (Hint: Not all documents support your side, find those that do): Document # What is the main idea of this document? What details support your position? 3. Work with your partner to summarize your arguments for your position using the supporting documents you found above: Position Presentation: 4. You and your partner will present your position to your opposing group members. When you are done, you will then listen to your opponents’ position. While you are listening to your opponents’ presentation, write down the main details that they present here: Clarifying questions I have for the opposing partners: How they answered the questions: Consensus Building: 5. Put your assigned roles aside. Where does your group stand on the question? Where does your group agree? Where does your group disagree? Your consensus answer does not have to be strictly yes, or no. We agree: We disagree: Our final consensus: