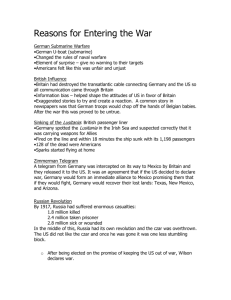

chapter 25 notes - Herbert Hoover High School

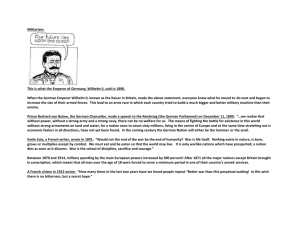

advertisement