An Outline of the U.S. Economy - Guangzhou, China

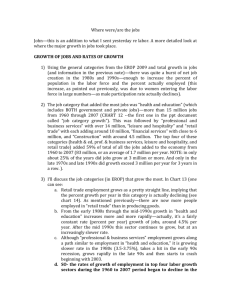

advertisement