The Novel Is Your Ticket to Real Travel

advertisement

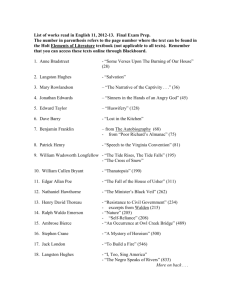

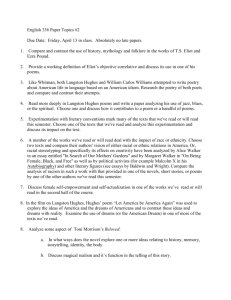

Unit Theme : Civil Rights Written by Chaya Felcher Objectives: 1. To emphasize the importance of reading. 2. To introduce the topic of civil rights in America In this unit you will find: 1. A speech by Amos Oz on the importance of reading as a bridge between different cultures. 2. The poem :"I too" by Langston Hughes 3. A short story: "A Mason – Dixon Memory" by Clifton Davis 4. An essay :"Notes on a Native Son" by James Baldwin ENJOY THE UNIT ! The Novel Is Your Ticket to Real Travel Amos Oz, the Israeli novelist, was awarded the Prince of Asturias Award for Literature last week. This is his acceptance lecture. The Times, November 3rd, 2007 If you buy a ticket and travel to another country, you are likely to see the monuments, the palaces and the squares, the museums and the landscapes and the historical sites. If you are lucky, you may have a chance to conduct some conversations with the local people. Then you will travel back home, carrying a bunch of photographs or postcards. But if you read a novel, you obtain a ticket into the most intimate recesses of another country and of another people. Reading a foreign novel is an invitation to visit other people's homes and other countries' private quarters. If you are a mere tourist, you might stand on a street and look up at an old house, in the old part of town, and see a woman staring out of her window. Then you will walk on. But if you are a reader, you can see that woman staring out of her window, but you are there with her, inside her room, inside her head. As you read a foreign novel, you are actually invited into other people's living rooms, into their nurseries and studies, into their bedrooms. You are invited into their secret sorrows, into their family joys, into their dreams. Which is why I believe in literature as a bridge between peoples. I believe curiosity can be a moral quality. I believe that imagining the other can be an antidote to fanaticism. Imagining the other will make you not only a better business person or a better lover, but even a better person. Part of the tragedy between Jew and Arab is the inability of so many of us, Jews and Arabs, to imagine each other. Really imagine each other: the loves, the terrible fears, the anger, the passion. There is too much hostility between us, too little curiosity. Jews and Arabs have something essential in common: they have both been handled, coarsely and brutally, by Europe's violent hand in the past. The Arabs - through imperialism, colonialism, exploitation and humiliations. The Jews through discrimination, persecution, expulsion, and ultimately mass murder on an unprecedented scale. One would have thought that two victims, and especially two victims of the same oppressor, develop between them a sense of solidarity. Alas, this is not the way it works, either in novels, or in life. Some of the worst conflicts are indeed between two victims of the same oppressor; two children of the same violent parent don't necessarily like each other. Often they see in each other the image of the abusive parent. Which is exactly the case between Jews and Arabs in the Middle East. While the Arabs regard Israelis as latterday crusaders, an extension of the white, colonising Europe, many Israelis, for their part, regard the Arabs as the new incarnation of our past oppressors, pogrom makers and Nazis. This situation charges Europe with a particular responsibility for the solution of the Israeli-Arab conflict: instead of wagging their fingers at either side, Europeans should extend empathy, understanding and help to both sides. You no longer have to choose between being pro-Israel and being pro-Palestine. You have to be pro-peace. The woman in the window might be a Palestinian woman in Nablus. She might be a Jewish-Israeli woman in Tel Aviv. If you want to help to make peace between these two women in the two windows, you had better read more about them. Read novels, dear friends. They will tell you much. It is even time for each of these women to read about each other. To learn, at last, what makes the other woman in the window frightened, angry, or hopeful. I have not suggested to you that reading novels can change the world. I did suggest, and I do believe, that reading novels is one of the best possible ways to understand that all the women, in all the windows, are at the end of the day, in urgent need of peace. Lesson Plan – Amos Oz Written by : Chaya Felcher Pre reading : Complete the sentences : Reading is important because……….. Reading to me is like ………………… Share students answers. While reading : Complete the sentence : For Amos Oz, reading is like ………… After reading : What does Oz compare reading to? Why? Why is it important to read in his opinion? How does he connect reading to the situation in the Middle East? Why is the conflict surprising according to Oz? Who is the woman in the window? Why is she there? Is he optimistic or not? Explain Follow up: Write a letter of response to Amos Oz relating to his speech. You may agree or disagree with him. Explain your opinion in the letter. Langston Hughes and the Harlem Renaissance Lesson plan adapted by Ahuva Dotan from Module F Literature Course, Matach - http://top.cet.ac.il/ Biography of Langston Hughes - Famous Poets Langston Hughes (February 1, 1902 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, novelist, playwright, short story writer, and newspaper columnist. Hughes is best known for his work during the Harlem Renaissance. Langston Hughes was born James Mercer Langston Hughes in Joplin, Missouri, the son of Carrie Langston Hughes, a teacher, and her husband, James Nathaniel Hughes. After abandoning his family and the resulting legal dissolution of the marriage later, James Hughes left for Cuba first, then Mexico due to enduring racism in the United States. After the separation of his parents, young Langston was left to be raised mainly by his grandmother, Mary Langston, as his mother sought employment. Through the black American oral tradition of storytelling, she would instill in the young Langston Hughes a sense of indelible racial pride. He spent most of childhood in Lawrence, Kansas. After the death of his grandmother, he went to live with family friends, James and Mary Reed, for two years. His childhood was not an entirely happy one, due to an unstable early life, but it was one that heavily influenced the poet he would become. Later, he lived again with his mother in Lincoln, Illinois who had remarried when he was still an adolescent, and eventually in Cleveland, Ohio where he attended high school. Langston Hughes in Cleveland, Ohio high school circa 1919-1920, he was designated class poet because of, Hughes said later as an adult, his race, African Americans then being stereotyped as having rhythm. "I was a victim of a stereotype. There were only two of us Negro kids in the whole class and our English teacher was always stressing the importance of rhythm in poetry. Well, everyone knows — except us — that all Negroes have rhythm, so they elected me as class poet." ….. Upon graduating from high school in June of 1920, Hughes returned to live with his father, hoping to convince him to provide money to attend Columbia University. Hughes later said that, prior to arriving in Mexico again, "I had been thinking about my father and his strange dislike of his own people. I didn't understand it, because I was a Negro, and I liked Negroes very much." … James Hughes did not support his son's desire to be a writer. Eventually, Langston and his father came to a compromise. Langston would study engineering so long as he could attend Columbia. His tuition provided, Hughes left his father after more than a year of living with him. While at Columbia in 1921, Hughes managed to maintain a B+ grade average. He left in 1922 because of racial prejudice within the institution, and his interests revolved more around the neighborhood of Harlem than his studies, though he continued writing poetry. Hughes' life and work were enormously influential during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s alongside those of his contemporaries, …. Hughes wrote what would be considered the manifesto for himself and his contemporaries published in The Nation in 1926, The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain: The younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn't matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly, too. The tom-tom cries, and the tom-tom laughs. If colored people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, their displeasure doesn't matter either. We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain free within ourselves. Hughes was unashamedly black at a time when blackness was démodé, and, he didn’t go much beyond the themes of black is beautiful as he explored the black human condition in a variety of depths. His main concern was the uplift of his people who he judged himself the adequate appreciator of and whose strengths, resiliency, courage, and humor he wanted to record as part of the general American experience. Thus, his poetry and fiction centered generally on insightful views of the working class lives of blacks in America, lives he portrayed as full of struggle, joy, laughter, and music. Permeating his work is pride in the African American identity and its diverse culture. "My seeking has been to explain and illuminate the Negro condition in America and obliquely that of all human kind," Hughes is quoted as saying. Therefore, in his work he confronted racial stereotypes, protested social conditions, and expanded African America’s image of itself; a “people’s poet” who sought to reeducate both audience and artist by lifting the theory of the black aesthetic into reality. Moreover, Hughes stressed the importance of a racial consciousness and cultural nationalism absent of self-hate that united people of African descent and Africa across the globe and encouraged pride in their own diverse black folk culture and black aesthetic. Langston Hughes was one of the few black writers of any consequence to champion racial consciousness as a source of inspiration for black artists. On May 22, 1967, Hughes died from complications after abdominal surgery related to prostate cancer at the age of 65. His ashes are interred beneath a floor medallion in the middle of the foyer leading to the auditorium named for him within the Arthur Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. Adapted from: http://www.todays-woman.net/article1666.html I, Too by Langston Hughes I, too, sing America. I am the darker brother. They send me to eat in the kitchen When company comes, But I laugh, And eat well, And grow strong. Tomorrow, I'll be at the table When company comes. Nobody'll dare Say to me, "Eat in the kitchen," Then. Besides, They'll see how beautiful I am And be ashamed-- o o o o o o o o o o o Who is the speaker of the poem? Where does the poem take place? Who sends him to eat in the kitchen? What does he do there? Who is the darker brother? What does eating and growing stronger represent? What is the significance of being at the table? "I, too, sing America." Who else sings? Compare the life of the master to the life of the dark brother Will the speaker be able to tell them he won't eat in the kitchen? What do you learn from the poem about the situation of the Blacks in that period? o How is life different today than what it used to be in the past? Post Reading Activity Students formulate a response relating the poem to the development of the Black Movement in the USA, or comparing it to something a bit closer to home here, with the more recent immigrants to Israel, or the Palestinians, for example. How are the issues raised in the poem relevant to 1) your life Or 2) life in Israel? Students choose ONE of the following tasks: o o o o Written Essay (180-200 words) Photo Essay / PPT (12-15 slides with meaningful captions between photos) Dramatic Presentation (at least 3 minutes in length) Rap/Song (original, at least 3 minutes in length) A Mason-Dixon Memory by Clifton Davis Read the following story. Have the students complete the worksheets at the end. Clifton Davis, born in 1945, is an American actor who starred on television shows such as That’s My Mama in the 1970s and on Amen in the 1980s. Davis has also acted on Broadway, and he was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Actor for his performance in a musical version of The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Before acting, Davis worked as a songwriter, most famously writing The Jackson 5’s #2 hit “Never Can Say Goodbye”. In addition to being an actor and a singer, he is also an ordained Seventh-day Adventist Church minister. He was raised in Long Island. Dondre Green glanced uneasily at the civic leaders and sports figures filling the hotel ballroom in Cleveland. They had come from across the nation to attend a fund-raiser for the National Minority College Golf Scholarship Foundation. I was the banquet's featured entertainer. Dondre, an 18-year- old high school senior from Monroe, Louisiana, was the evening's honored guest. "Nervous?" I asked the handsome young man in his starched white shirt and rented tuxedo. "A little," he whispered, grinning. One month earlier, Dondre had been just one more black student attending a predominately white school. Although most of his friends and classmates were white, Dondre's race was never an issue. Then, on April 17, l991, Dondre's black skin provoked an incident that made nationwide news. "Ladies and gentlemen," the emcee said, "our special guest, Dondre Green." As the audience stood applauding, Dondre walked to the microphone and began his story. "I love golf," he said quietly. "For the past two years, I've been a member of the St. Frederick High School golf team. And though I was the only black member, I've always felt at home playing at mostly white country clubs across Louisiana." The audience leaned forward; even the waiters and busboys stopped to listen. As I listened, a memory buried in my heart since childhood fought its way to life. "Our team had driven from Monroe," Dondre continued. "When we arrived at the Caldwell Parish Country Club in Columbia, we walked to the putting green." Dondre and his teammates were too absorbed to notice the conversation between a man and St. Frederick athletic director James Murphy. After disappearing into the clubhouse, Murphy returned to his players. "I want to see the seniors," he said. "On the double!" His face seemed strained as he gathered the four students, including Dondre. "I don't know how to tell you this," he said, "but the Caldwell Parish Country Club is reserved for whites only." Murphy paused and looked at Dondre. His teammates glanced at each other in disbelief. "I want you seniors to decide what our response should be," Murphy continued. "If we leave, we forfeit this tournament. If we stay, Dondre can't play." As I listened, my own childhood memory from 32 years ago broke free. In 1959, I was 13 years old, a poor black kid living with my mother and stepfather in a small black ghetto on Long Island, New York. My mother worked nights in a hospital, and my stepfather drove a coal truck. Needless to say, our standard of living was somewhat short of the American dream. Nevertheless, when my eighth-grade teacher announced a graduation trip to Washington, D.C., it never crossed my mind that I would be left behind. Besides a complete tour of the nation's capital, we would visit Glen Echo Amusement Park in Maryland. In my imagination, Glen Echo was Disneyland, Knott's Berry Farm and Magic Mountain rolled into one. My heart beating wildly, I raced home to deliver the mimeographed letter describing the journey. But when my mother saw how much the trip cost, she just shook her head. We couldn't afford it. After feeling sad for 10 seconds, I decided to try to fund the trip myself. For the next eight weeks, I sold candy bars door-to-door, delivered newspapers and mowed lawns, Three days before the deadline, I'd made just barely enough. I was going! The day of the trip, trembling with excitement, I climbed onto the train. I was the only nonwhite in our section. Our hotel was not far from the White House. My roommate was Frank Miller, the son of a businessman. Leaning together out of our window and dropping water balloons on tourists quickly cemented our new friendship. Every morning, almost a hundred of us loaded noisily onto our bus for another adventure. We sang our school fight song dozens of times, en route to Arlington National Cemetery and even on an afternoon cruise down the Potomac River. We visited the Lincoln Memorial twice, once in daylight, the second time at dusk. My classmates and I fell silent as we walked in the shadows of those 36 marble columns, one for every state in the Union that Lincoln labored to preserve. I stood next to Frank at the base of the 19-foot seated statue. Spotlights made the white Georgian marble glow. Together, we read those famous words from Lincoln's speech at Gettysburg remembering the most bloody battle in the War between the States: "...we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain - that this nation, under God shall have a new birth of freedom..." As Frank motioned me into place to take my picture, I took one last look at Lincoln's face. He seemed alive and so terribly sad. The next morning, I understood a little better why he wasn't smiling. "Clifton," a chaperone said, "could I see you for a moment?" The other guys at my table, especially Frank, turned pale. We had been joking about the previous night's direct water-balloon hit on a fat lady and her poodle. It was a stupid, dangerous act, but luckily nobody got hurt. We were celebrating our escape from punishment when the chaperone asked to see me. "Clifton," she began, "do you know about the Mason- Dixon line?" "No," I said, wondering what this had to do with drenching fat ladies. "Before the Civil War," she explained, "the Mason-Dixon line was originally the boundary between Maryland and Pennsylvania - the dividing line between the slave and free states." Having escaped one disaster, I could feel another brewing. I noticed that her eyes were damp and her hands were shaking. "Today," she continued, "the MasonDixon line is a kind of invisible border between the North and the South. When you cross that invisible line out of Washington, D.C., into Maryland, things change." There was an ominous drift to this conversation, but I wasn't following it. Why did she look and sound so nervous? "Glen Echo Amusement Park is in Maryland," she said at last, "and the management doesn't allow Negroes inside." She stared at me in silence. I was still grinning and nodding when the meaning finally sank in. "You mean I can't go to the park," I stuttered, "because I'm a Negro?" She nodded slowly. "I'm sorry, Clifton," she said, taking my hand. "You'll have to stay in the hotel tonight. Why don't you and I watch a movie on television?" I walked to the elevators feeling confusion, disbelief, anger and a deep sadness. "What happened, Clifton?" Frank said when I got back to the room. "Did the fat lady tell on us?" Without saying a word, I walked over to my bed, lay down and cried. Frank was stunned into silence. Junior-high boys didn't cry, at least not in front of each other. It wasn't just missing the class adventure that made me feel so sad. For the first time in my life, I learned what it felt like to be a "nigger." Of course there was discrimination in the North, but the color of my skin had never officially kept me out of a coffee shop, a church - or an amusement park. "Clifton," Frank whispered, "what is the matter?" "They won't let me to go Glen Echo Park tonight," I sobbed. "Because of the water balloon?" he asked. "No, I answered, "because I'm a Negro." "Well, that's a relief!" Frank said, and then he laughed, obviously relieved to have escaped punishment for our caper with the balloons. "I thought it was serious." Wiping away the tears with my sleeve, I stared at him. "It is serious. They don't let Negroes into the park. I can't go with you!" I shouted. "That's pretty damn serious to me." I was about to wipe the silly grin off Frank's face with a blow to his jaw when I heard him say, "Then I won't go either." For an instant we just froze. Then Frank grinned. I will never forget that moment. Frank was just a kid. He wanted to go to that amusement park as much as I did, but there was something even more important than the class night out. Still, he didn't explain or expand. The next thing I knew, the room was filled with kids listening to Frank. "They don't allow Negroes in the park," he said, "so I'm staying with Clifton." "Me, too," a second boy said. "Those jerks," a third muttered. "I'm with you,Clifton." My heart raced. Suddenly, I was not alone. A pint- sized revolution had been born. The "water-balloon brigade," 11 white boys from Long Island, had made its decision: "We won't go." And as I sat on my bed in the center of it all, I felt grateful. But, above all, I was filled with pride. Dondre Green's story brought that childhood memory back to life. His golfing teammates, like my childhood friends, faced an important decision. If they stood by their friend it would cost them dearly. But when it came time to decide, no one hesitated. “Let's get out of here," one of them whispered. "They just turned and walked toward the van," Dondre told us. "They didn't debate it. And the younger players joined us without looking back." Dondre was astounded by the response of his friends - and the people of Louisiana. The whole state was outraged and tried to make it right. The Louisiana House of Representatives proclaimed a Dondre Green Day and passed legislation permitting lawsuits for damages, attorneys' fees and court costs against any private facility that invites a team, then bars any member because of race. As Dondre concluded, his eyes glistened with tears. "I love my coach and my teammates for sticking by me," he said. "It goes to show that there always good people who will not give in to bigotry. The kind of love they showed me that day will conquer hatred every time." Suddenly the banquet crowd was standing, applauding Dondre Green. My friends, too, had shown that kind of love. As we sat in the hotel, a chaperone came in waving an envelope. Boys!" he shouted. "I've just bought 13 tickets to the Senators-Tigers game. Anybody want to go?" The room erupted in cheers. Not one of us had ever been to a professional baseball game in a real baseball park. On the way to the stadium, we grew silent as our driver paused before the Lincoln Memorial. For one long moment, I stared through the marble pillars at Mr. Lincoln, bathed in that warm, yellow light. There was still no smile and no sign of hope in his sad and tired eyes. "...We here highly resolve...that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom..." In his words and in his life, Lincoln made it clear, that freedom is not free. Every time the color of a person's skin keeps him out of an amusement park or off a country- club fairway, the war for freedom begins again. Sometimes the battle is fought with fists and guns, but more often the most effective weapon is a simple act of love and courage. Whenever I hear those words from Lincoln’s speech at Gettysburg, I remember my eleven white friends, and I feel hope once again. I like to imagine that when we paused that night at the foot of his great monument, Mr. Lincoln smiled at last. As Dondre said, “The kind of love they showed me that day will conquer hatred every time.” A Mason – Dixon Memory Lesson Plan Written by Ahuva Dotan Set Induction: a. Write all your associations thinking of "friendship" OR b. Complete the following sentence: "Friendship is……." Class Discussion: Elicit answers from students. Conduct a class discussion defining "friendship" While Reading: Teacher reads story out loud. Ask students to look for the answers to the following questions: Who is the speaker? What takes him back to his childhood? What incident does he share with Dondre Green? Class Discussion: Were you surprised by anything in the story? Why was Clifton afraid when a chaperone wanted to speak to him? Was his fear justified? Why not? What did the chaperone tell him? How did he feel? How did his friends react? Do they come from the same background? Why was he "the evening's honored guest"? Had he ever encountered any racial discrimination before? How did his friends react to the club's refusal to accept Dondre? Are Dondre Green and Clifton Davis the same age? What do these two incidents show about American Society? What do you think is the message of the story? How would you behave if you faced a conflict like his friends? Is the story realistic today? Yes/ no , explain Why is the story called "A Mason-Dixon Memory"? Is the story pessimistic? Prove ! Why is President Lincoln mentioned in the story? Post Reading: Look for information about President Lincoln's Gettysburg Address. Sum up the information you find. What is his message? Has President Lincoln's dream come true in The U.S.A. of 2009 ? A Mason Dixon Memory by Clifton Davis Fill in the worksheet. Clifton’s friends did not go. where?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . when? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . why? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Expanded sentence (Start with the when.) _________________________________________________________________ Directions: Complete the following sentences. Clifton Davis' friends were like Dondre Green's teammatesbecause__________________ _________________________________________________________________ Clifton Davis' friends were like Dondre Green's teammates but ______________ _________________________________________________________________ Clifton Davis' friends were like Dondre Green's teammates so _________________________________________________________________ Before the team arrived at Caldwell Parish Country Club, _________________________________________________________________________ When Dondre’s friends walked off the golf course, _________________________________________________________________ Although the coach knew the policy was wrong,____ _________________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ After the nation became aware of Dondre’s experience, _____________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ For the Teacher possible answers In the late fifties, Clifton’s friends did not go to the amusement park because they wanted to stand by him. During his childhood, Clifton’s friends did not go to the amusement park because they knew prejudice was wrong. ......................................... Clifton Davis' friends were like Dondre Green's teammates .... because both groups were good friends who stood up for the right thing. but the events took place about thirty years apart. so it brought back memories for Mr. Davis. ......................................... Before the team arrived at Caldwell Parish Country Club, they were excited about the tournament. When Dondre’s friends walked off the golf course, they made a statement against bigotry. Although the coach knew the policy was wrong, he still let the players decide what to do about the competition. After the nation became aware of Dondre’s experience, Louisiana passed legislation barring such practices. Notes of a Native Son By James Baldwin The year which preceded my father's death had made a great change in my life. I had been living in New Jersey, working in defense plants, working and living among southerners, white and black. I knew about the south, of course, and about how southerners treated Negroes and how they expected them to behave, but it had never entered my mind that anyone would look at me and expect me to behave that way. I learned in New Jersey that to be a Negro meant, precisely, that one was never looked at but was simply at the mercy of the reflexes the color of one's skin caused in other people. I acted in New Jersey as I had always acted, that is as though I thought a great deal of myself----I had to act that way----with results that were, simply, unbelievable. I had scarcely arrived before I had earned the enmity, which was extraordinarily ingenious, of all my superiors and nearly all my co-workers. In the beginning, to make matters worse, I simply did not know what was happening. I did not know what I had done, and I shortly began to wonder what anyone could possibly do, to bring about such unanimous, active, and unbearably vocal hostility. I knew about jim-crow but I had never experienced it. I went to the same self-service restaurant three times and stood with all the Princeton boys before the counter, waiting for a hamburger and coffee; it was always an extraordinarily long time before anything was set before me; but it was not until the fourth visit that I learned that, in fact, nothing had ever been set before me: I had simply picked something up. Negroes were not served here, I was told, and they had been waiting for me to realize that I was the only Negro present. Once I was told this, I determined to go there all the time. But now they were ready for me and, though some dreadful scenes were subsequently enacted in that restaurant, I never ate there again. It was the same story all over New Jersey, in bars, bowling alleys, diners, places to live. I was always being forced to leave, silently, or with mutual imprecations. I very shortly became notorious and children giggled behind me when I passed and their elders whispered or shouted----they really believed that I was mad. And it did begin to work on my mind, of course; I began to be afraid to go anywhere and to compensate for this I went places to which I really should not have gone and where, God knows, I had no desire to be. My reputation in town naturally enhanced my reputation at work and my working day became one long series of acrobatics designed to keep me out of trouble. I cannot say that these acrobatics succeeded. It began to seem that the machinery of the organization I worked for was turning over, day and night, with but one aim: to eject me. I was fired once, and contrived, with the aid of a friend from New York, to get back on the payroll; was fired again, and bounced back again. It took a while to fire me for the third time, but the third time took. There were no loopholes anywhere. There was not even any way of getting back inside the gates. That year in New Jersey lives in my mind as though it were the year during which, having an unsuspected predilection for it, I first contracted some dread, chronic disease, the unfailing symptom of which is a kind of blind fever, a pounding in the skull and fire in the bowel. Once this disease is contracted, one can never be really carefree again, for the fever without an instant's warning, can recur at any moment. It can wreck more important things than race relations. There is not a Negro alive who does not have this rage in his blood----one has the choice, merely, of living with it consciously or surrendering to it. As for me, this fever has recurred in me, and does, and will until the day I die. My last night in New Jersey, a white friend from New York took me to the nearest big town, Trenton, to go to the movies and have a few drinks. As it turned out, he also saved me from, at the very least, a violent whipping. Almost every detail of that night stands out very clearly in my memory. I even remember the name of the movie we saw because its title impressed me as being so partly ironical. It was a movie about the German occupation of France, starring Maureen O' Hara and Charles Laughton and called This Land Is Mine. I remember the name of the diner we walked into when the movie ended: it was the "American Diner." When we walked in the counterman asked what we wanted and I remember answering with the casual sharpness which had become my habit: "We want a hamburger and a cup of coffee, what do you think we want?" I do not know why, after a year of such rebuffs, I so completely failed to anticipate his answer, which was, of course, "We don't serve Negroes here." This reply failed to discompose me, at least for the moment. I made some sardonic comment about the name of the diner and we walked out into the streets. This was the time of what was called the "brown-out", when the lights in all American cities were very dim. When we rentered the streets something happened to me which had the force of an optical illusion, or a nightmare. The streets were very crowded and I was facing north. People were moving in every direction but it seemed to me, in that instant, that all of the people I could see, and many more than that, were moving toward me, against me, and that everyone was white. I remember how their faces gleamed. And I felt, like a physical sensation, a click at the nape of my neck as though some interior string connecting my head to my body had been cut. I began to walk. I heard my friend call after me, but I ignored him. Heaven only knows what was going on in his mind, but he had the good sense not to touch me----I don't know what would have happened if he had----and to keep me in sight. I don't know what was going on in my mind, either; I certainly had no conscious plan. I wanted to do something to crush these white faces, which were crushing me. I walked for perhaps a block or two until I came to an enormous, glittering, and fashionable restaurant in which I knew not even the intercession of the Virgin would cause me to be served. I pushed through the doors and took the first vacant seat I saw, at a table for two, and waited. I do not know how long I waited and I rather wonder, until today, what I could possibly have looked like. Whatever I looked like, I frightened the waitress who shortly appeared, and the moment she appeared all my fury flowed towards her. I hated her for her white face, and for her great, astounded, frightened eyes. I felt that if she found a black man so frightening I would make her fright worthwhile. She did not ask me what I wanted, but repeated, as though she had learned it somewhere, "We don't serve Negroes here." She did not say it with the blunt, derisive hostility to which I had grown so accustomed, but, rather, with a note of apology in her voice, and fear. This made me colder and more murderous than ever. I felt I had to do something with my hands. I wanted her to come close enough for me to get her neck between my hands. So I pretended not to have understand her, hoping to draw her closer. And she did step a very short step closer, with her pencil poised incongruously over her pad, and repeated the formula:"...don't serve Negroes here." Somehow, with the repetition of that phrase, which was already ringing in my head like a thousand bells of a nightmare, I realized that she would never come any closer and that I would have to strike from a distance. There was nothing on the table but an ordinary water-mug half full of water, and I picked this up and hurled it with all my strength at her. She ducked and it missed her and shattered against the mirror behind the bar. And, with that sound, my frozen blood abruptly thawed, I returned from wherever I had been, I saw, for the first time, the restaurant, the people with their mouths open, already, as it seemed to me, rising as one man, and I realized what I had done, and where I was, and I was frightened. I rose and began running for the door. A round, potbellied man grabbed me by the nape of the neck just as I reached the doors and began to beat me about the face. I kicked him and got loose and ran into the streets. My friend whispered, "Run!" and I ran. My friend stayed outside the restaurant long enough to misdirect my pursuers and the police, who arrived, at once. I do not know what I said to him when he came to my room that night. I could not have said much. I felt, in the oddest, most awful way, that I had somehow betrayed him. I lived it over and over again, the way one relived an automobile accident after it has happened and one finds oneself alone and safe. I could not get over two facts, both equally difficult for the imagination to grasp, and one was that I could have been murdered. But the other was that I had been ready to commit murder. I saw nothing very clearly but I did see this: that my life, my real life, was in danger, and not from anything other people might do but from the hatred I carried in my own heart. Lesson Plan Adapted from It Stands to Reason by Natalie Hess and Evelyn Ezra Pre Reading: Divide the class into groups. Give each group a card on which one of the following titles is written. Each group discusses the possible meaning of the title and tries to predict what the story is about. Each group reports to the class. Card 1 Task: What is the meaning of this sentence? What is the essay going to be about? Card 2 Task: What is the meaning of the sentence? What is the essay going to be about? Card 3 Task: What is the meaning of the sentence? What is the essay going to be about? Discussion: Is there any connection between these titles? Do they give you any idea of the issues Baldwin deals with in his essay? When you hear the word "serve" what are the assiociations that come to your mind? Are they mainly positive or negative? Ask students to make their lists of associations in pairs. (Possible associations: serve a meal, serve in a tennis game, serve in the army, serve a person (as a servant), serve a sentence in jail, serve one's country) Reading: While reading look for the three titles discussed before. What do they refer to? Post Reading Discussion: Baldwin's character remembers the title of the movie he saw, This Land is Mine, with irony. Why? Why is "The American Diner" also an ironic name in the context of the essay? What was the standard answer that the author received in the diner? Retell the incident in the second restaurant from the point of view of the waitress. Why do you think the narrator felt he had to do something with his hands? Consider the last sentence. Previously Baldwin says that he "lived that night over and over again". Can you explain why? List the expressions of anger in the essay. List the expressions of fear. What is the connection between this essay and the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S. ? Think and discuss : How did the narrator experience racism? How did it affect him? Why did he lose his temper ? How did he feel afterwards? What do you think happened afterwards ? ( He escaped to Paris and lived there for many years) What do you think is the message of this essay?