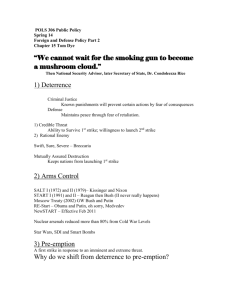

Deterrence Operations

advertisement