Alejandro Ricaño`s Idiots Contemplating the Snow

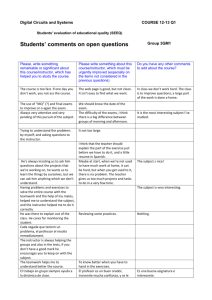

advertisement