Texas and the Death Penalty

advertisement

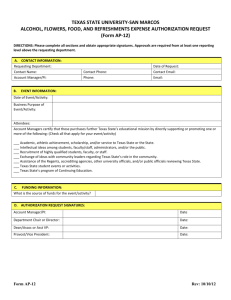

Abstract (Document Summary) Texas had about 38,000 murders from 1976 to 1998 in which people older than 16 were arrested, according to the study, which relied on F.B.I. data. Only California had more, about 50,000. The number of murders in Texas, more than anything else, explains the 776 death sentences that were issued during roughly the same period, the study concluded. ''It tells you there are absolutely massive post-sentencing differences,'' said Theodore Eisenberg, a law professor at Cornell and an author of the study, sponsored by the Cornell Law School Death Penalty Project, which provides legal services to death-row inmates. The other authors are John Blume, the director of the project, and Martin T. Wells, a professor of statistics at Cornell. Authors of the Cornell study said, though, that race still did have an impact. The available data are not comprehensive, but they suggest that the race of the victim has a large effect on sentences. In Virginia, for instance, blacks who murdered blacks were sentenced to death 0.4 percent of the time, while blacks who murdered whites were sentenced to death 6.4 percent of the time. The rate for white killers of whites was 1.8 percent; for white killers of blacks, 2.3 percent. Full Text (1659 words) Copyright New York Times Company Feb 14, 2004 Texas, generally considered the leading death penalty state, actually sentences a smaller percentage of people convicted of murder to death than the national average, according to a new study. It found that the conventional view failed to take into account the large number of murders in Texas. As a percentage of murders, Nevada and Oklahoma impose the most death sentences, at 6 and 5.1 percent. In Texas, the percentage is 2 percent. The rate in Virginia, another state noted for its commitment to capital punishment, is 1.3 percent. The national average is 2.5 percent; the median is 2 percent. ''Texas's reputation as a death-prone state should rest on its many murders and on its willingness to execute death-sentenced inmates,'' wrote the authors of the study, published in a new publication, the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies. ''It should not rest on the false belief that Texas has a high rate of sentencing convicted murderers to death.'' Using the same analysis, the study concluded that blacks are actually underrepresented on the nation's death row. Blacks commit 51.5 percent of all murders nationally but constitute about 42 percent of death row inmates, the study found. Texas had about 38,000 murders from 1976 to 1998 in which people older than 16 were arrested, according to the study, which relied on F.B.I. data. Only California had more, about 50,000. The number of murders in Texas, more than anything else, explains the 776 death sentences that were issued during roughly the same period, the study concluded. The study used arrest records as a proxy for convictions. It did not exclude people who were arrested but not prosecuted or not convicted. This did not affect the study's conclusions, its authors write, ''because erroneous murder arrests are of concern only if they vary unevenly across states.'' The study does not consider execution rates. Prisoners on death row in Texas are more likely to be executed than in many other states. As of this week, Texas has executed 319 people since 1976. California, by contrast, sentenced 795 people to death from 1976 through 2002 and has executed only 10. Comparing execution statistics from the Justice Department with the number of murders the study cited, though, a different picture emerges. The chances that a convicted murderer was executed in the United States in the years in question was a little more than 0.2 percent. In Texas, the corresponding number was, at 0.5 percent, substantially higher. But even by this measure, Texas trails Delaware, at 1.6 percent; Virginia, at 0.8 percent; and Missouri, at 0.6 percent. The difference between the sentencing rate in Texas, which trails the national average, and the execution rate, which exceeds it, suggests that what takes place after convictions accounts for Texas's reputation. Texas juries are no more likely to impose death sentences than their counterparts elsewhere, but appeals courts and prosecutors in the state are more likely to ensure that sentences are carried out. ''It tells you there are absolutely massive post-sentencing differences,'' said Theodore Eisenberg, a law professor at Cornell and an author of the study, sponsored by the Cornell Law School Death Penalty Project, which provides legal services to death-row inmates. The other authors are John Blume, the director of the project, and Martin T. Wells, a professor of statistics at Cornell. But Professor Eisenberg emphasized that the sentencing rate is independently significant. ''Putting someone on death row is a major decision of the state,'' he said. Focusing on Texas, he added, obscures the level of activity elsewhere. ''The reality is that the most death-prone states are under the radar,'' he said, citing Nevada and Oklahoma. Capital defense lawyers in Texas and elsewhere said the study's conclusions were accurate but incomplete. ''It's misleading to look at Texas as a whole,'' said David Dow, a law professor at the University of Houston who often represents capital defendants. ''In Texas, the death penalty is not spread out equally.'' For instance, Professor Dow said, 158 of the 450 inmates on death row in Texas are from Harris County, which includes Houston. Professor Eisenberg countered that the large number of murders in Harris County explains that disparity, too. ''Harris County is in the middle of Texas in terms of death sentences,'' he said. ''Harris County is to Texas as Texas is to the nation.'' Executions are, again, a separate question. Of the 317 executions in Texas in the last three decades, 70 were of people convicted in Harris County -- more than any other county in the nation. The study considered several explanations for the range in sentencing rates, which is less than 1 percent in Colorado, Maryland, New Mexico and Washington State and more than 4 percent in Arizona, Idaho, Delaware, Oklahoma and Nevada. State laws make a significant difference, the study found. Laws that limit the availability of the death penalty to specific kinds of murder, like that of a police officer or witness, have lower death sentencing rates than those that use more subjective standards, like whether a murder was particularly heinous or atrocious. The states with more objective standards, including Texas, have an average sentencing rate of 1.9 percent; the states with more subjective standards have an average sentencing rate of 2.7 percent. In states where juries or a panel of judges made the final sentencing decision, the average rate was 2.1 percent. In cases in which a single judge -- typically an elected judge -- made the decision, the rate was 4.1 percent. The availability of life without parole as an alternative to a death penalty did not correlate with a lower death sentencing rate, a conclusion that the authors wrote was ''opposite to the expected effect.'' Nor did Southern states have higher death sentencing rates than the rest of the country. The significance of race in death sentences is complicated, the study found. At the most general level, though, what little effect the defendant's race appeared to have on the sentencing rate operated in favor of black defendants. That conclusion is not new, but death penalty supporters contend that it has been underreported. ''We have somehow managed,'' Robert Blecker, a professor at New York Law School writes in a forthcoming essay, ''in the death penalty context to overcome centuries of embedded racism and administer a system of ultimate punishment where defendants will be judged more nearly by the circumstances of their crimes and the contents of their character than by the color of their skin.'' Authors of the Cornell study said, though, that race still did have an impact. The available data are not comprehensive, but they suggest that the race of the victim has a large effect on sentences. In Virginia, for instance, blacks who murdered blacks were sentenced to death 0.4 percent of the time, while blacks who murdered whites were sentenced to death 6.4 percent of the time. The rate for white killers of whites was 1.8 percent; for white killers of blacks, 2.3 percent. That black defendants fare differently depending on the race of their victim is well known. But that the race of the defendant has a separate impact when the victim is white is news, the study says. ''The existence of a broad race-of-defendant effect, found here in different death sentence rates for black defendant-white victim cases and white defendant-white victim cases, has been virtually undetectable in more than 50 previous empirical studies,'' the authors write. According to the Justice Department, black murder victims were killed by blacks 94 percent of the time and white murder victims were killed by whites 86 percent of the time. ''This tendency,'' the study concluded, ''swamps the increased black presence on death row attributable to the harsh treatment of black defendant-white victim cases.'' [Chart] ''Reappraising Death Row'' A study comparing the number of death sentences issued in a state with the number of murders committed there found that Texas -- often considered to be the leading death penalty state -- sends a smaller percentage of murderers to death row than the national average. Texas does have one of the highest rates of executing inmates once they reach death row. Death sentences per 1,000 murders For the 31 states with more than 10 death row enrollees from 1977 to 1999 WASH.: 9 ORE.: 20 CALIF.: 13 IDAHO: 47 NEV.: 60 ARIZ.: 43 UTAH: 18 COLO.: 4 N.M.: 7 TEXAS: 20 OKLA.: 51 NEB.: 23 MO.: 24 ARK.: 20 LA.: 16 MISS.: 35 ALA.: 38 TENN.: 20 ILL.: 19 IND.: 16 KY.: 14 OHIO: 28 FLA.: 34 GA.: 22 S.C.: 16 N.C.: 26 VA.: 13 N.J.: 10 DEL.: 48 MD.: 7 PA.: 24 States with the most death sentences per 1,000 murders Nev. DEATH SENTENCES: 124 MURDERS: 2,072 RATE PER 1,000: 60 Okla. DEATH SENTENCES: 257 MURDERS: 5,020 RATE PER 1,000: 51 Del. DEATH SENTENCES: 30 MURDERS: 626 RATE PER 1,000: 48 Idaho DEATH SENTENCES: 36 MURDERS: 773 RATE PER 1,000: 47 Ariz. DEATH SENTENCES: 213 MURDERS: 5,007 RATE PER 1,000: 43 States with the most executions, as a percentage of death row Va. DEATH ROW INMATES: 119 EXECUTIONS: 73 PCT.: 61% Del. DEATH ROW INMATES: 30 EXECUTIONS: 10 PCT.: 33 Utah DEATH ROW INMATES: 19 EXECUTIONS: 6 PCT.: 32 Mo. DEATH ROW INMATES: 158 EXECUTIONS: 41 PCT.: 26 Texas DEATH ROW INMATES: 776 EXECUTIONS: 198 PCT.: 26 Death sentence rate, by race of offender and victim For seven states* that were able to provide racial data for 1977 to 2000 White victim, black offender: 66 death sentences per 1,000 murders White victim, white offender: 26 Black victim, white offender: 19 Black victim, black offender: 7 * Georgia, Indiana, Maryland, Nevada, Pennsylvania, South Carolina and Virginia. (Source by ''Explaining Death Row's Population and Racial Composition,'' John Blume, Theodore Eisenberg and Martin T. Wells of the Cornell Law School Death Penalty Project; Death Penalty Information Center) Map of the United States highlighting the states that have (1-15, 16-30, 30-45, 45-60) death row enrollees, fewer than 10 death sentences, and no death penalty.