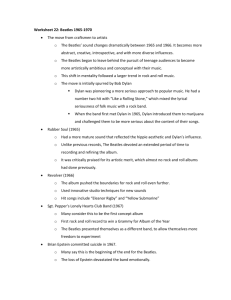

revised Beatles Evolution 1

The Evolution of Critical Regard for the Beatles’ Revolver

B. Keith Gottberg

“What is your favorite Beatles album?” …Since the first day I heard it, Revolver has always been the right answer… Revolver has been shocking, provoking, frightening, and delighting listeners with its lyrical beauty and sonic wonder – spoken, sung, wailed, archaic, pop, atmospheric, acoustic, electronic, impossible, and some almost terrifyingly futuristic – for over thirty five years, and… its grip on the collective imaginations shows no sign of loosening. Revolver remains a haunting, soothing, confusing, grandly complex and ambitious statement about the possibilities of popular music… 1

Among music fans, Russel Reising’s comment could engender all manner of discussion and argument. Music creates a deep emotional attachment for the avid listener. Music attaches to memories and first experiences. People experience moments of ecstasy, like a first kiss, and moments of tragedy, like the loss of a loved one, while connected to music. Those same songs take the emotion of the individual into their very essence. One cannot help but remember that experience when listening to that song.

This context makes it very dangerous to say that one album supercedes another.

For each individual will bring their own experiences into the argument, experiences that another listener could not possibly understand. An album grabs a person because of their emotional attachment. To insult someone’s favorite album is to insult them. If their album does not measure up, then they do not measure up.

Still, we strive to put the whole scope of Western music under the microscope.

As humans we must have rationale and order. Feelings cannot be allowed to interfere.

We must have a superior item. We must have a measuring stick against which we can compare anything new. There must be order, even in the universe of passion – i.e. music.

The same creative impulse that created the spontaneous expression of sound in the first place also compels us to order that spontaneity into an understandable spectrum.

We create our endless lists for such a purpose. We argue and debate over which is the greatest in our search for order. We must have our mental heuristics, our shortcuts of measurement. If a listener must measure every new song against those they have already heard, an enormous amount of brain power is wasted. They would probably cease to enjoy music at all after they had stored six or seven songs. If we have a favorite song or album in mind already, or at very least an abbreviated list, it makes the comparison much faster and easier.

The Beatles’

Revolver holds a place of particular importance because it often tops those short lists. What gives Revolver such an important place? Why does it hold a special place in the hearts of so many to this day? How did the public respond to the LP when the Beatles created the music and how has the response evolved since?

Critics praised the groundbreaking nature of the Beatles’ Revolver upon its release in August 1966. However, the album did not receive the full accolade it deserved

1 Russel Reising, Every Sound There Is: The Beatles Revolver and the transformation of Rock and Roll

(Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2002), 1.

because the original United States release did not have the full compliment of songs – it was not until the compact disc release that the missing songs completed the experience.

Revolver finally picked up momentum and surpassed the Beatles’ more dated Sgt.

Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (among others) to take its place atop many “greatest” lists around the turn of the 21 st

century. Many critics, past and present, see Revolver as the apex, the turning point, of the Beatles career and creativity. Ultimately, Revolver has taken its place as the most pivotal album of the Beatles’ career. The release of the full album for American audiences in the late 1980s, the advent of a new generation of

Beatles listeners, the reevaluation afforded by the release of the Beatles Anthology, and the beginning of a new millennium elevated Revolver to the forefront of critical acclaim and recognized its position at a turning point of Beatles’ craftsmanship, internal band dynamics, and 1960s technology.

The background for Revolver differs from any of the Beatles’ albums that preceded it. The Beatles took the time to create and polish their sound unlike with earlier recordings. It took as much time to record the Revolver song “Yellow Submarine” as it did the Beatles’ entire first LP.

2

By early 1966 the Beatles had also begun experimenting with mind-altering drugs.

3

The band members used marijuana heavily while recording the album Rubber

Soul the year before, but they had now begun to experiment with LSD and its ability to seemingly expand one’s consciousness. Songwriter/bassist/vocalist Paul McCartney would later claim that LSD only directly influenced the song “Tomorrow Never Knows”, but the experience may have affected writing and recording in other ways.

4

The release of Revolver on August 5, 1966, in the United Kingdom and August 8 th in the United States came at a turbulent point in the Beatles career.

5

Comments earlier in the year by singer/guitarist John Lennon concerning the band’s popularity exceeding that of Jesus offended many traditional evangelical Christians in the southern United States.

By August 13, twenty-two radio stations had begun to boycott the Beatles in the South, but they remained the exception.

6

Most stations in the United States ignored the boycott.

7

In spite of the controversy the Beatles embarked on a tour to the United States from

August 12 th to the 30 th .

8 It would be their last tour ever. The chaos and screaming typical of the Beatles’ concert experience remained as strong as ever and sent the Beatles running for cover from obsessive fans on at least one occasion.

9

The controversy certainly did not hurt the Beatles’ on the charts or in the record stores. The “Yellow Submarine”/“Eleanor Rigby” single entered the British charts at #4 and took the top spot within a week.

10

By the end of the month, “Yellow Submarine” was #1 in Los Angeles and #5 across the United States.

11

The album as a whole also sat

2 Walter Everett, The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver through Anthology (New York: Oxford University

Press, 1999), 57.

3 The Beatles, The Beatles Anthology (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2000).

4 William J. Dowdling, Beatlesongs (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1989), 146.

5 Dowdling, 131; Philip Cowan, Behind the Beatles Songs (London: Polytantric, 1978), 51.

6 “Beatles to Face Knockers,” Melody Maker , August 13, 1966.

7 Ren Grevatt, “Radio Stations Ignore Ban on Beatles Records,” Melody Maker , August 20, 1966.

8 “Beatles to Face Knockers;” Gravatt; Cowan, 27.

9 Grevatt.

10 Richard Goldstein, “Pop Eye: On Revolver, ” Village Voice XI, no. 45 (1966): 23, 26.

11 “Tops in Pops,” Los Angeles Times , August 31, 1966. PHN.

atop the American charts. Revolver sales reached $1 million in the first two weeks, an impressive number since the stereo version of the record was being sold for $2.99 and the mono version for $2.39.

12 Songwriters John Lennon and Paul McCartney received an award at the Ivor Novello Awards for “Yellow Submarine” when the single achieved the highest certified British sales of 1966.

13

Throughout its history, the masses have revered Revolver for the many reasons that its critics and scholars also express. But more than just fan adulation, the album is so critical, so important, because it sits atop the crossroads of the Beatles career, and thus a turning point in rock and roll history. The Beatles and music changed for good after this album.

It marked the step from traditional pop music like “Eleanor Rigby” into something more progressive like “Yellow Submarine” or “Tomorrow Never Knows”.

14

Rubber Soul showed the Beatles moving into “the aristocracy of popular song,” but

Revolver completely shattered the conventions of pop music.

15

Rock and roll and the new culture it ushered in no longer belonged only to the young. The Beatles passed from

“teen idols” to “storytellers.

16 The critics began to receive the Beatles music as genuine art with the release of the unconventional Revolver.

17

It not only bridged the old and the avant garde, but it bridged the natural and the artificial as well.

18

The sixties existed in a time of new technologies and a shrinking world. By embracing electronics and the electronic sounds produced through tape recorders and all manner of new production equipment, The Beatles, the symbols of their generation, helped to humanize technology.

19

The band seemed to understand that this was the beginning of something new.

“Tomorrow Never Knows,” the first song recorded for the album, was originally titled

“Mark 1.”

Revolver finally realized the “serious artistic ambitions” that the band had strived for in Rubber Soul.

20

Even the Beatles as musicians took a great step forward. Guitarist and sometime songwriter George Harrison improved in both crafts when he wrote and played on

“Taxman.” 21

John Lennon’s voice had by this point reached an enviable quality of expressiveness.

22 The production team even allowed the Beatles to experiment electronically, leading to the psychedelic tape loops of “Tomorrow Never Know” and the creation of Artificial Double Tracking, a system by which a producer can achieve the

12 “Earning Curve 1966 and All That,” Management Today , September 2006. EBSCO; “Display Ad 379,”

Los Angeles Times , August 21, 1966. PHN.

13 “Two Beatles Win Song Awards,” The Times (London), March 27, 1967, 10.

14 Hunter Davies, The Beatles: The Authorized Biography (New York: Dell, 1968), 294.

15 George Melly in Terrence John O’Grady, “The Music of the Beatles from 1962 to Sergeant Pepper’s

Lonely Hearts Club Band ” (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin at Madison, 1975), 311.

16 Charles Paul Freund, “Still Fab: Why We Keep Listening to the Beatles,” Reason 33, no. 2(June 2001),

56-63. EBSCO.

17 Wilfred Mellers in O’Grady, 311.

18 Nick Bromell, Tomorrow Never Knows: Rock and Psychedelics in the 1960s (Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 2000), 96.

19 Bromell, 96.

20 Everett, 34.

21 O’Grady, 325.

22 John Robinson in Everett, 48.

thicker sound of multiple recordings by simply altering the timing of recording.

23

In addition to the “tabla and sitar, tape loops, instruments played backward, brass bands, and submarine sound effects” Revolver possessed some of the best lyrics that the Beatles’ had ever written.

24

On Revolver the Beatles used a string quartet without a guitar or rhythm section for the first time. They used eastern wisdom in their lyrics for the first time.

They used a book for lyrics for the first time.

25 Revolver just broke all of the rules.

The Beatles would influence, perhaps even parody, themselves. David Quantick of Q magazine commented on this acme of the Beatles’ career:

There’s a case to be made that The Beatles went on to do

Sergeant

Pepper’s

because there was nowhere else to go but too far. With

Revolver , they had mapped out the pop universe so perfectly that all they could do next was tear it up and start again.

Revolver leaped ahead from the super pop of Rubber Soul , while finding a focus absent in the later Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.

26

The Beatles recorded the LP at the end of their touring days. They would become more of a studio band after Revolver.

27

This album made Beatlemania irrelevant.

28

Why continue to endure the hardships of crazed fans and hard tours when you can create incredibly unique music in a studio that would be impossible to duplicate elsewhere? This was also the beginning of the end for the Beatles. Without the life of touring to unite them, each of the four members would discover their own lives and their own interests. These diverging passions ultimately grew larger as the band pulled itself apart in its final years.

29

However, the growing individuality of the band members actually aided the music during the recording of Revolver . The band members each shared their own ideas and unique traits while still working within the strong team framework of a touring band.

30

Such shared music disappeared as the band members grew apart. Later, each recorded and fought for their own creations without significantly aiding the offerings of their mates. The Beatles , better known as the White Album, released a couple years later had to be released as a double-album because the three principle songwriters all refused to have any of their material omitted from the finished product.

The critics loved Revolver from the start .

When the album released in 1966, the

Los Angeles Times lauded the new LP as “best album they have made”.

31

Two years later a reviewer in the New York Times already placed it as a “Landmark of Rock”.

32

One

23 Mark Lewishon, “Beatles ’66: The Revolver Sessions,” Musician , October 1988, 28-32, 105.

24 Dowlding, 131.

25 Kingshuk Niyogy, “You Can’t Do That (or How the Beatles Broke the Rules and Made New Ones),” The

Statesman (India), June 14, 2002. LN.

26 David Quantick in Reising, 2.

27 Davies, 294.

28 Tim Riley, The Beatles: album by album, song by song, the sixties and after (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo

Press, 1998), 176.

29 Everett, 31.

30 Naphtali Wagner in Reising, 119.

31 Pete Johnson, “New Beatles Album Best Yet,” Los Angeles Times , August 7, 1966. PQ.

32 “Landmarks of Rock,” New York Times , August 25, 1968. PQ.

journalist remarked that it until “Eleanor Rigby” he did not realize that the Beatles could do anything lyrically other than “Yea Yea Yea”.

33

At the 9 th

Annual Grammy Awards in the United States, “Eleanor Rigby” took home the award for Best Male Vocal in the

Contemporary Idiom.

34

Other winners included more traditional fare like the legendary

Frank Sinatra.

In one of the earliest examples of a “greatest” list, Ivan March in 1967 included the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

and the “experimental” and

“imaginative”

Revolver in a book filled mostly with classical, jazz, and other traditional music genres.

35

The critics favorably compared The Beatles to poetry and jazz.

36

They had redefined what popular music could and should be as an art form. Richard Goldstein in the Village Voice best expressed the groundbreaking nature of the new album:

“ Revolver is a revolutionary record, as important to the expansion of pop territory as was Rubber Soul

…

Revolver is the great leap forward.

Hear it once and you know it’s important. Hear it twice it makes sense.

Third time around its fun. Fourth time it’s subtle. On the fifth hearing

Revolver becomes profound.”

37

The boundaries, he argued, had changed as to what could be called pop music.

38

A door to whole new world of experimentation had opened.

If imitation stands as the sincerest form of flattery, then the Beatles’ and Revolver received admiration in that form as well. “Yellow Submarine” led to bands trying to create a kind of nursery pop.

39 The string quartet in “Eleanor Rigby” led to a renewed interest in classical music, and guitarist George Harrison’s interest in Indian music (as evidenced by “Love You To”) led to more curiosity for Oriental styles.

40

The Beatles also stood at the forefront of the electronic and psychedelic music that dominated the later half of the 1960s.

41

There was even satirical opera based on Revolver. Among the work created by opera soloist Cathy Berberian and company is a version of “Yellow

Submarine” done in the style of 18 th

-century Singspiel.

42

A small minority did not like the album. Some of the material was labeled as

“mediocre” by critics like Goldstein and others did not find McCartney’s electronics or

Harrison’s sitar aurally enjoyable.

43

Pop star turned pundit Jonathan King called it

33 Alan Aldridge in Jonathan Eisen, ed, The Age of Rock: Sounds of the American Cultural Revolution

(New York: Vintage Books, 1969), 139.

34 Charles Champlin, “Sinatra Wins 6 Honors in 9 th Grammy Awards,” Los Angels Times , March 3, 1967.

PQ.

35 Ivan March, The Great Records (Blackpool: Long Playing Record Library, 1967), 119.

36 Benjamin Demott, “Rock as Salvation,” New York Times, August 25, 1969. PQ; Eisen, 197.

37 Goldstein, 26.

38 Goldstein, 26.

39 William Mann, “The Beatles Revive Hopes of Progress in Pop Music,” The Times (London), May 29,

1967, 9.

40 Mann.

41 Mann.

42 Thomas Willis, “Gift Suggestions No. 2: Why Not Test Out the Far-Out?”, Chicago Tribune , November

26, 1967. PQ.

43 Goldstein, 26; Ned Rorem, “The Music of the Beatles”, Music Educators Journal 55, no. 4 (December

1968):81. JSTOR , www.jstor.org.

“pseudo-intellectual rubbish,” and as with any daring change, there were a “few conservative Beatlemaniacs” that wanted to go back to the simpler style of the Beatles’ earlier recordings.

44 These reactionaries and detractors were atypical. Nevertheless, fans soon forgot Revolver after the daring and over-the-top

Sgt Pepper’s

released the following year.

Many artists, albums, and songs seem to go through a kind of “middle age.” A netherworld engulfs the music after the band has quit touring and making music. The music ages beyond the ever-changing trends of popularity, but does not yet spark a deep nostalgia. If the music survives, it may eventually pass into this realm of “classic rock” and could even see a revival in some form or another by a new generation (see: Oasis).

Revolver had even more to overcome during its period of middle age than many of the other Beatles albums. By 1970, the year the Beatles broke up, Revolver stood only tenth in American sales among Beatles albums.

45 Every one of those Beatles albums that followed Revolver except Yellow Submarine had sold more in the United States in a shorter period of time. Though always too popular to be overlooked, in the 1970s and

1980s Revolver and the Beatles fell out of the main public eye and into the realm scholars and elite critics.

After the Beatles’ parted ways in 1970, scholars and historians began to look for the band’s place in history. The entire discography, including

Revolver, has been examined several times since. One of the first to try was Wilfrid Mellers in 1973. He places the album “halfway between ritual and art.”

46

Mellers felt the album looked at love from a different perspective than its saccharine predecessors. The anti-establishment message of “Taxman” represented anti-love and the utter loneliness of “Eleanor Rigby” shows a world longing for love but not reaching it.

47

Revolver shows the world as a far more sober place than earlier Beatles works. Ultimately Mellers calls the recording

“a breakthrough from the world of pop into a world that hasn’t been yet categorized.” 48

Still, he does not disconnect Revolver from

Sgt Pepper’s

or Abbey Road, considering the three the collective peak of Beatles achievement.

Two years later Terrance John O’Grady also explored the Beatles’ meaning in his

PhD dissertation. The Beatles had become a legitimate subject for academic study. He, however, ignored their “final period of retrenchment” as he felt it did not “explore any new musical ground.” 49

The “experimental and unprecedented” nature and originality of

Revolver impressed O’Grady.

50 But he also did not single out the album as the Beatles’ greatest, citing Revolver and

Sgt Pepper’s as the “pinnacle of the Beatles’ progressive stylistic evolution.” 51

Music critics and fans placed Revolver among their favorites during the 1970s. In a 1978 survey in the Los Angeles Times , the LP received two nominations as the greatest album ever and finished #6 overall among a panel of 48 music experts.

52

In 1981, a fan

44 Nicholas Schaffner, The Beatles Forever (New York: Mcgraw-Hill, 1977), 64.

45 Everett, 67.

46 Wilfrid Mellers, Twilight of the Gods: The Beatles in Retrospect (London: Faber & Faber, 1973), 69.

47 Mellers, 70.

48 Mellers, 125.

49 O’Grady, 8.

50 O’Grady, 349.

51 O’Grady, 10.

52 Robert Hilburn, “Sgt. Pepper: Greatest LP?”, Los Angeles Times , February 3, 1978. PQ.

writer in Melody Maker included Revolver in his five favorite albums because of its

“sheer tunefulness.” 53

Revolver fell hardest from popular acclaim in the mid- to late-80s. The aura of the sixties had worn off. In 1974, Revolver had come in 4 th

in NME’s list of the top albums of all-time (though it was still behind #1 Sgt Pepper’s ). In 1985, the Beatles failed to even make the top ten.

54 In Rolling Stone magazine’s 1987 rankings of the “100

Greatest Albums of the Rock Era,”

Revolver placed only 17th behind three other Beatles albums.

55

Even as late as 1995, the Encyclopedia of Rock and Roll mentions Revolver only in passing in an otherwise extensive Beatles entry.

56

During the 1980s there was no longer a sense of wonder. Technological changes did not initially aid the aging music. “Songs that had once been magical… sounded thin” when they were transferred from LP to CD.

57

Even with remastering, those that first heard the album on vinyl as children may have found the warmth and emotional response of their initial listening missing as they returned in those years of middle age. The music of the 80s was big on large, extravagant synthesized sounds and wild, loud metal guitar.

How could this generation sit down and enjoy the simple depth of the Beatles?

Despite this loss of interest, 1987 also saw the seeds of a Revolver revival. The

CD release of the album that year finally included the full 14 track collection for the first time in the United States.

58

Lennon’s “I’m Only Sleeping,” “And Your Bird Can Sing,” and “Doctor Robert” had been omitted from the original release because the Beatles’

American distributor, Capital Records, had included the songs on an EP of old and new

Beatles material earlier in that 1966 summer.

59

Revolver would begin its ascent in popularity as the large American audience finally heard the recording as intended. The rerelease certainly aided its rise up the many lists around the turn of the century.

60

The last fifteen years have seen resurgence in the Beatles’ and especially

Revolver

’s popularity

. Relatively little surfaced immediately following the CD release, but by 1993, Revolver rose up to second on NME’s top 100 list.

Mojo magazine placed the album 3rd in 1996 with four other Beatles albums in the top 33.

61

A 1999 poll of

Melody Maker

’s writers placed

Revolver 4 th

.

62

The once so competitive

Sgt. Pepper’s

did not place in their top 100 at all. Q magazine placed Revolver at the top of their list in

2000 and six total Beatles albums in the top 21 citing the album’s “astonishing mix of styles with a weirdly consistent purpose.” 63

Revolver would be 2 nd

in Q in 2004 and 4 th

53 B. Hinton, “All Grown Up: Revolver ,” Melody Maker 56 (March 28, 1991):15.

54 Andrew Smith, “Shots at a Pop Cannon,” The Sunday Times (London), June 2, 1996. LN.

55 Reising, 2.

56 Reising, 2.

57 Robert Palmer, “Stones on Disks,” New York Times , October 21, 1984. PQ.

58 Phil Gallo, “Here, There & Everywhere,” Variety , January 22, 2001, 70.

59 Reising, 194.

60 “Beatles Tops of the Pops: Classic Album Revolver Named Number One on Experts’ List of 100,” The

Mercury (Hobart), January 6, 2001. EBSCO.

61 Smith.

62 “The Queen is Dead, Long Live the King of Albums,” Birmingham Post , December 30, 1999. LN.

63 Jim McLean, “What Goes Around Comes Around: Revolver is Best Album”, TheHerald (Glasgow), May

2, 2000. LN.

in 2008.

64

Also in 2000, Revolver topped the Virgin All Time Top 1000.

65

Cable music channel VH1 crowned their list with the “invulnerable” Revolver in 2001.

66

The quintessential American music magazine Rolling Stone issued their list of the top 500 albums in 2003. They placed Revolver at #3 behind the album’s old rival, a #1

Sgt. Pepper’s

.

67

However, Revolver took first in a side bar by Billie Joe Armstrong, the lead singer of popular pop-punk band Green Day.

68 It took second behind Bob Dylan in the German version of Rolling Stone the following year.

69

It is clear in all of these polls that Revolver , at least in recent history, must be included on any short list of great albums.

The timing of such polls really aided the resurgence of the Beatles discography.

Most of the Beatles’ music had come out on CD by the turn of the century. Also, new autobiographical works like The Beatles Anthology , released in 2000, and the video series that preceded it a few years before kept the band fresh in the mind of the public. With the

Beatles at the forefront of public consciousness, fans and critics happily placed the

Beatles atop many of their best lists.

In 1998, Virgin took a poll among the customers that visited their stores with

Revolver rated #1 and three other Beatles offerings in the top 5.

70

What surprised the pollsters was the nature of the voters. Almost all of the teenager entries had at least one

Beatles album in their top 20, and many placed Revolver ahead of the highly popular bands Oasis and Radiohead. When questioned, the teenagers expressed that they had grown up with the Beatles songs as nursery rhymes and that they really enjoyed the depth that the Beatles always maintained. The children of the first Beatles listeners had inherited their parents love for the music.

In fact, many of the people now buying the Beatles’ CDs and downloads, many of the people voting for them in polls, did not first listen to the band until long after they had broken up. Many were not even born. Phil Gallo suggests that Revolver has slowly grown its popularity because of this fresh look at the music:

On a track-by-track basis, there’s nothing (on Revolver ) that anyone would want to skip over. It’s the album that marks the transition from moptop to psychedelic, and each track is perfectly written, perfectly sung, perfectly arranged.

71

The high rankings in the polls also coincided with renewed scholarly and critical interest in the Beatles and their music. Tim Riley took a stab at the breaking down the

64 Charles Spencer, “Irresistible Best List,” The Spectator , June 12, 2004. LN; “Oasis Bigger than Beatles:

Fab Four Knocked Off Their Pedestal in British Music Poll World,” Illiwara Mercury , February 20, 2008.

EBSCO.

65 Reising, 3.

66 “Beatles Tops of the Pops”

67 Pat Blashill, et al, “The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time,” Rolling Stone , December 11, 2003. EBSCO.

68 Billie Joe Armstrong, “My Top Ten,” Rolling Stone , December 11, 2003. EBSCO.

69 “Bob’s Blonde pips the Beatles,” The Daily Telegraph (Sydney), November 2, 2004. EBSCO.

70 Lacey Hester, “Still with the Beatles: Isn’t Something Wrong if Today’s Teenagers Really Rate Mum’s and Dad’s Fave Raves Ahead of Oasis and Radiohead?”, The Independent (London), September 13, 1998.

LN.

71 Gallo, 70.

Beatles song by song in 1998. He countered the support typically given for

Sgt. Pepper’s by stating that it remained a “flawed masterpiece that can only echo the strength of

Revolver.

” 72 The year after, Walter Everett published the “first work to attempt a comprehensive historical, descriptive, and analytic discussion of the compositions.” 73

Everett stood awed by Revolver

’s “new sounds” and “creative wizardry.” 74

In 2002, a number of highly educated Revolver fanatics put together Every Sound There Is: The

Beatles Revolver and the transformation of rock and roll to show their appreciation for the album that, at the time, had seemingly become everyone’s favorite. In the compilation they vowed to show that Revolver

, as the “album of ‘firsts’ and ‘onlies’ in the Beatles’ canon,” had blazed a path that changed not only the direction of the Beatles, but all rock and roll music that followed.

75

Spurred on by the album’s 40 th

anniversary and the advent of a new millennium, critics began to take a second look at the album and its place in history. The album had not grown old in the eyes of the reviewers. They even claimed to find something new and interesting upon repeat listening.

76

It was pulled out of “the crate” and admired for its “master list” of “incredibly poignant” songs.

77 The LP could still draw awe at its imagination even four decades later; perhaps even more so because the reviewers now knew just how much it hinted at what was to come later in rock music.

78

Revolver even has its share of fan-researched material. Ray Newman’s online book Abracadabra!

attempts to understand the influences that led to the album’s differences.

79

His work is more an in-depth history of the influences leading up to

Revolver than an analysis, but there is no questioning the dedication and interest that this album can inspire.

Revolver enjoyed a renaissance in critical acclaim because of its modern relevance and its critical place in Beatles’ history. Critics and fans received the album with open arms upon its release in spite of the new methods and experiences surrounding its recording and the controversy present during its release and the subsequent tour. After the Beatles broke up, academics subjected their discography to the first of many scholarly approaches. Still, the Beatles seemingly fell out of favor with a new generation. This changed when Revolver finally arrived in its entirety in United States. The children of the Beatles’ generation grew up listening to their parents’ favorite band. Their inherited love led to the new generation’s favorite album, Revolver, adorning the top of most of the turn of the century greatest album lists and the Beatles’ music being the subject of further scholarly review.

Revolver withstood the test of time because of its place at the crossroads. It fell between the traditional and novel. It marked the transition into a new world with new

72 Riley, 203.

73 Steven Block, Review of The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver through Anthology, by Walter Everett,

Notes 57, no. 1 (2000): 158.

74 Walter Everett, 33.

75 Reising, 11.

76 Stephen Valdez in Reising, 107.

77 Chris Johnson, “The Crate – Revolver (1966),” The Age (Melbourne), June 10, 2005. EBSCO.

78 Steve Waldon, “Fab and 40, Revolver Rocks On,” The Age (Melbourne), August 5, 2006. EBSCO.

79 Ray Newman, Abracadabra! The Complete Story of the Beatles’ Revolver, http://www.revolverbook.co.uk/abracadabrav1.0.pdf (accessed October 7, 2008).

technology. For the Beatles personally, it was the end of their time as a teamwork-strong touring band and the beginning of a studio band full of individuality.

If we must have order - if we must have an album to use as the standard for all others - then we would be hard pressed to find an album that is more sufficient than

Revolver . For so many fans from the time of its release until today, this album sparks all of the emotional responses that make people passionate about their music. It has even drawn the affection of a generation that was not even conceived at the time of its 1966 release. Revolver is the greatest album ever.

Bibliography

Armstrong, Billie Joe. “My Top Ten.” Rolling Stone , December 11, 2003. EBSCO.

Aspinall, Neil. “Neil’s Column.”

The Beatles Monthly Book , April 1966.

---. “Neil’s Column.” The Beatles Monthly Book , August 1966.

---. “Neil’s Column.” The Beatles Monthly Book , September 1966.

Beatles, The. The Beatles Anthology.

San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2000.

Beatles, The. Revolver.

Parlaphone compact disc CDP 7464412.

“Beatles Plus Jazzmen on New Album.” Melody Maker , June 11, 1966.

“Beatles to Face Knockers.”

Melody Maker , August 13, 1966.

“Beatles Tops of the Pops: Classic Album Revolver Named Number One on Experts’

List of 100.”

The Mercury (Hobart), January 6, 2001. EBSCO.

Bernard, Jonathan. Review of The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver through the

Anthology, by Walter Everett. Music Spectrum Theory 25, no. 2 (Autumn 2003):

375-382. JSTOR . www.jstor.org.

Blashill, Pat, et al. “The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.” Rolling Stone , December 11,

2003. EBSCO.

Block, Steven. Review of The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver through the Anthology, by

Walter Everett. Notes 57, no. 1 (2000): 157-159. WorldCat. www.worldcat.org.

“Bob’s Blonde pips The Beatles.” The Daily Telegraph (Sydney), November 2, 2004.

EBSCO.

Bromell, Nick. Tomorrow Never Knows: Rock and Psychedelics in the 1960s.

Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 2000.

Champlin, Charles. “Sinatra Wins 6 Honors in 9 th

Grammy Awards.” Los Angeles Times .

March 3, 1967. PQ.

Cowan, Philip. Behind the Beatles Songs . London: Polytantric, 1978.

Davies, Hunter. The Beatles: The Authorized Biography . New York: Dell, 1968.

DeMott, Benjamin. “Rock as Salvation.”

New York Times , August 25, 1969. PQ.

Digby, Diehl. “More Beatles Lyrics – in Psychedelic Array.”

Los Angeles Times , July 18,

1971. PQ.

“Display Ad 379.” Los Angeles Times , August 21, 1966, sec M24. PQ.

Dowlding, William J. Beatlesongs . New York: Simon & Schuster, 1989.

“Dylan Beats Beatles in German Poll.” The Gold Coast Bulletin , November 2, 2004.

EBSCO.

“Earning Curve 1966 and All That.”

Management Today , September 2006. EBSCO.

Eisen, Johathan, ed. The Age of Rock: Sounds of the American Cultural Revolution .

New York: Vintage Books, 1969.

Everett, Walter. The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver through the Anthology. New York:

Oxford University Press, 1999.

Freund, Charles Paul. “Still Fab: Why We Keep Listening to the Beatles.” Reason 33, no.

2 (June 2001): 56-63. EBSCO.

Gallo, Phil. “Here, There & Everywhere.”

Variety , January 22, 2001. EBSCO.

Gloag, Kenneth. Review of The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver through the Anthology, by Tim Riley. Music Analysis 22, no. 1-2 (2003): 231-237.

Goldstein, Richard. “Pop Eye: On

Revolver.

”

Village Voice XI, no. 45 (1966): 23, 26.

Grevatt, Ren. “Radio Stations Ignore Ban on Beatles Records.”

Melody Maker , August

20, 1966.

Haslop, Richard. “Afterhours – The Beatles Revolver Survives the Test of Time.”

Business Day (South Africa), May 23, 2000. LN.

Hester, Lacey. “Still with the Beatles: Isn’t There Something Wrong if Today’s

Teenagers Really Rate Mum’s and Dad’s Fave Raves Ahead of Oasis and

Radiohead?”.

The Indpendent (London), September 13, 1998. LN.

Hilburn, Robert. “

Sgt. Pepper

: Greatest LP?”.

Los Angeles Times , February 3, 1978. PQ.

Hinton, B. “All Grown Up:

Revolver.

”

Melody Maker 56 (March 28, 1981): 15.

Holm-Hudson, Kevin. Review of Every Sound There Is: The Beatles Revolver and the transformation of rock and roll , by Russel Reising, ed. Psychology of Music 33, no. 2 (2005): 217-220.

Hughes, Robert. “ Passing Along His Favorites: Stew, the Tony-nominated Star of

Passing Strange on Albums He Loves.”

Wall Street Journal , June 6, 2008. PQ.

Inglis, Ian. Review of Every Sound There Is: The Beatles Revolver and the transformation of rock and roll , by Russel Reising, ed. Popular Music 22, no. 3

(2003): 381-381.

“Is Any Beatles Album Worth Half an Hour of Your Life?”

Sunday Mercury , March 5,

2006. LN.

Johnson, Chris. “The Crate – Revolver (1966).” The Age (Melbourne), June 10, 2005.

EBSCO.

Johnson, Pete. “New Beatles Album Best Yet.”

Los Angeles Times , August 7, 1966. PQ.

---. “Summertime Songs on the Heat Parade.” Los Angeles Times , August 28, 1966. PQ.

Kramer, Rita. “It’s Time to Start Listening.” New York Times , September 17, 1967. PQ.

“Landmarks of Rock.” New York Times , August 25, 1968. PQ.

Lewishon, Mark. “Beatles ’66: The

Revolver Sessions.” Musician , October 1988, 28-32,

105.

Mann, William. “The Beatles Revive Hopes of Progress in Pop Music.”

The Times

(London), May 29, 1967, 9.

March, Ivan. The Great Records . Blackpool: Long Playing Record Library, 1967.

McLean, Jim. “What Goes Around Comes Around: Revolver is Best Album.” TheHerald

(Glasgow), May 2, 2000. LN.

Mellers, Wilfrid. Twilight of the Gods: The Beatles in Retrospect.

London: Faber &

Faber, 1973.

Miles, Barry. “The Tripping Point: The Making of the Beatles’ Album

Revolver

.”

Mojo ,

July 2006, 70-77.

Newman, Ray.

Abracadabra! The Complete Story of the Beatles’

Revolver. http://www.revolverbook.co.uk/abracadabrav1.0.pdf (accessed October 7, 2008).

Niyogy, Kingshuk. “You Can’t Do That (or How the Beatles Broke the Rules and Made

New Ones).” The Statesman (India), June 14, 2002. LN.

“Oasis Bigger than Beatles: Fab Four Knocked Off Their Pedestal in British Music Poll

World.”

Illawarra Mercury , February 20, 2008. EBSCO.

O’Grady, Terence John. “The music of the Beatles from 1962 to Sergeant Pepper’s

Lonely Hearts Club Band

.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin at Madison, 1975.

Palmer, Robert. “Stones on Disks.”

New York Times , October 21, 1984. PQ.

“The Queen is Dead, Long Live the King of Albums.” Birmingham Post , December 30,

1999. LN.

Randall, Mac. “The Sound of Music: Ten Albums that Changed the Art of Rock Record

Production.”

Musician , July 1977, 38.

Reising, Russel, ed. Every Sound There Is: The Beatles Revolver and the transformation of rock and roll . Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2002.

Riley, Tim. The Beatles: album by album, song by song, the sixties and after. Cambridge,

MA: Da Capo Press, 1998.

Rorem, Ned. “The Music of the Beatles.”

Music Educators Journal 55, no. 4 (December

1968): 33-34, 78-83. JSTOR.

www.jstor.org.

Salter, Lionel. Review of The Great Records , by Ivan March, ed. The Musical Times 109, no. 1500 (February 1968):145. JSTOR.

www.jsotr.org.

Savage, Jon. “100 Greatest Psychedelic Classics.” Mojo , June 1997, 56-67.

Sawyers, June Skinner. Read The Beatles: Classic and New Writings on the Beatles,

Their Legacy and Why They Still Matter.

New York: Penguin Books, 2006.

Schaffner, Nicholas. The Beatles Forever.

New York: McGraw-Hill, 1977.

Simms, Bryan R. The Music of the Twentieth Century: Style and Structure. New York:

Schirmer, 1986.

Spencer, Charles. “Irresistible Best List.”

The Spectator , June 12, 2004. LN.

Smith, Andrew. “Shots at a Pop Cannon.” The Sunday Times (London), June 2, 1996.

LN.

“Tops in Pops.”

Los Angeles Times , August 25, 1966, sec. D14. PQ.

“Tops in Pops.” Los Angeles Times , August 31, 1966, sec. D9. PQ.

“Two Beatles Win Song Awards.” The Times (London), March 27, 1967, 10.

Waldon, Steve. “Fab and 40,

Revolver Rocks On.” The Age (Melbourne), August 5, 2006.

EBSCO.

Wiener, Jon. Come Together: John Lennon in His Time . Urbana and Chicago:

University of Illinois Press, 1984.

Willis, Thomas. “Records: From Kurt Weill to Henze, Plus Bernstein and Beatle

Echoes.” Chicago Tribune , September 4, 1966. PQ.

---. “Gift Suggestions No. 2:Why Not Test Out the Far-Out?”. Chicago Tribune ,

November 26, 1967. PQ.