What is Queer Theory?

Queer theory is a set of ideas based around the idea that identities are not fixed and

do not determine who we are. It suggests that it is meaningless to talk in general

about 'women' or any other group, as identities consist of so many elements that to

assume that people can be seen collectively on the basis of one shared characteristic is

wrong. Indeed, it proposes that we deliberately challenge all notions of fixed identity, in varied

and non-predictable ways.

Queer theory is based, in part,

on the work of Judith Butler

(in particular her book

Gender Trouble, 1990).

It is a mistake to think that queer theory is another name for lesbian and gay studies. They're

different. Queer theory has something to say to lesbian and gay studies -- and also to a bunch

of other areas of sociology and cultural theory

Judith Butler

This page gives an introduction to Judith Butler and the arguments put forward in her 1990

book Gender Trouble. Her subsequent publications (see bibliography at the bottom of this

page) are covered here less. There are also links to a good student essay on Butler, and

some interview extracts (both on this site), as well as web resources on other sites. Our queer

theory pages have also expanded -- now featuring reviews and discussion of criticisms of

queer theory.

Who is Judith Butler?

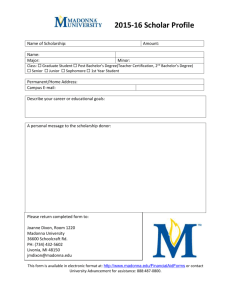

Judith Butler (1956-) is Professor of Comparative Literature and

Rhetoric at the University of California, Berkeley, and is well known as a

theorist of power, gender, sexuality and identity. Indeed, she is

described in alt.culture as "one of the superstars of '90s academia, with

a devoted following of grad students nationwide". (A fanzine, Judy!, was

published in 1993).

What has she said?

In her most influential book Gender Trouble (1990), Butler argued that

feminism had made a mistake by trying to assert that 'women' were a

group with common characteristics and interests. That approach, Butler

said, performed 'an unwitting regulation and reification of gender

relations' -- reinforcing a binary view of gender relations in which human

beings are divided into two clear-cut groups, women and men. Rather

than opening up possibilities for a person to form and choose their own

individual identity, therefore, feminism had closed the options down.

Butler notes that feminists rejected the idea that biology is destiny, but then developed an

account of patriarchal culture which assumed that masculine and feminine genders would

inevitably be built, by culture, upon 'male' and 'female' bodies, making the same destiny just

as inescapable. That argument allows no room for choice, difference or resistance.

Butler prefers 'those historical and anthropological positions that understand gender as a

relation among socially constituted subjects in specifiable contexts'. In other words, rather

than being a fixed attribute in a person, gender should be seen as a fluid variable which shifts

and changes in different contexts and at different times.

The very fact that women and men can say that they feel more or

less 'like a woman' or 'like a man' shows, Butler points out, that 'the

experience of a gendered... cultural identity is considered an

achievement.'

Butler argues that sex (male, female) is seen to cause gender

(masculine, feminine) which is seen to cause desire (towards the other

gender). This is seen as a kind of continuum. Butler's approach -inspired in part by Foucault -- is basically to smash the supposed links

between these, so that gender and desire are flexible, free-floating and

not 'caused' by other stable factors.

Butler says: 'There is no gender identity behind the expressions of

gender; ... identity is performatively constituted by the very

"expressions" that are said to be its results.' (Gender Trouble, p. 25). In other words, gender

is a performance; it's what you do at particular times, rather than a universal who you are.

Butler suggests that certain cultural configurations of gender have seized a hegemonic hold

(i.e. they have come to seem natural in our culture as it presently is) -- but, she suggests, it

doesn't have to be that way. Rather than proposing some utopian vision, with no idea of how

we might get to such a state, Butler calls for subversive action in the present: 'gender trouble'

-- the mobilization, subversive confusion, and proliferation of genders -- and therefore identity.

Butler argues that we all put on a gender performance, whether traditional or not, anyway,

and so it is not a question of whether to do a gender performance, but what form that

performance will take. By choosing to be different about it, we might work to change gender

norms and the binary understanding of masculinity and femininity.

This idea of identity as free-floating, as not connected to an 'essence', but instead a

performance, is one of the key ideas in queer theory. Seen in this way, our identities,

gendered and otherwise, do not express some authentic inner "core" self but are the dramatic

effect (rather than the cause) of our performances.

David Halperin has said, 'Queer is by definition whatever is at odds with the normal, the

legitimate, the dominant. There is nothing in particular to which it necessarily refers. It is an

identity without an essence.'

It's not (necessarily) just a view on sexuality, or gender. It also suggests that the confines of

any identity can potentially be reinvented by its owner...

And finally -- what has this got to do with media and communications studies? Well, the

call for gender trouble has obvious media implications, since the mass media is the primary

means for alternative images to be disseminated. The media is therefore the site upon which

this 'semiotic war' (a war of symbols, of how things are represented) would take place.

Madonna is one media icon who can be seen to have brought queer theory to the masses.

Madonna and Gender Trouble

By Reena Mistry

With her constant image changes, parodies of blonde bombshells such as Marilyn Monroe,

her assertion of female power and sexuality, and her appropriation from gay/queer culture,

the popular music icon Madonna can be seen as the virtual embodiment of Judith Butler's

arguments in Gender Trouble (1990, 1999). In this postmodern feminist text, which is credited

with introducing 'queer theory' to the world, Butler critiques identity-based politics as the

method for female emancipation, claiming that presenting 'women' as a coherent group

performs 'an unwitting regulation and reification of [binary] gender relations' (1999:9). She

exposes and derationalizes the social power systems that construct the norms regarding the

'natural' gender identities of men and women, the 'logic' of heterosexuality, and the idea of a

pre-discursive core gender identity, through which women are subordinated, and

homosexuals, cross-dressers, and those others who are located beyond the 'imaginable

domain of gender', are marginalised (ibid:13). Butler suggests that 'subversive' identities

demonstrating the constructedness of sex-gender-desire continuity will work to destroy its

normative status, thus allowing all 'cultural configurations of sex and gender [to] proliferate'

and become intelligible (i.e. not deviant) (ibid:190). In that Madonna parodies traditional

female stereotypes and adopts at her will identities that 'contradict' herself as a heterosexual

female, Butler's idea of the ability for a 'variable construction of identity' (ibid:9) beyond

traditional binary constructions is exposed. Further therefore, people are not restricted to (in

addition to 'traditional' gender identities) the empowered female, gay and lesbian; in true

queer theory style, 'one could participate in a range of identities - such as the lesbian

heterosexual, a heterosexual lesbian, a male lesbian, a female gay man, or even a feminist

sex-radical' (Schwichtenberg 1993:141). Indeed, Madonna has demonstrated such fluidity

and ambiguity through her sexual political work - notably in the music videos for Vogue,

Erotica and Justify My Love, her film Truth or Dare: In Bed With

Madonna, and her book Sex.

The strong connection between Madonna and Gender Trouble is not one

that has gone unnoticed; a number of writers on popular culture, queer

politics and feminism have given it much consideration (see for example

Kaplan 1993, Schwichtenberg 1993 and Skeggs 1993). Within such

discussions - and others in 'Madonna Studies' - however, there is

evidence suggestive of a limit on the extent to which Madonna can be

seen to epitomise Butler's arguments. Moreover, she can be seen to

contradict the aim of subversive politics, despite her public support of gay rights, her AIDS

charity work and her 'flirtations' with lesbianism (Robertson 1996:119). Hence critics have

started to ask: "Is Madonna a glamorized fuckdoll or the queen of parodic critique?" (ibid:118).

The ways in which Madonna can be seen to contradict the political recommendations of

Gender Trouble are complex and stem from a number of critical perspectives - hence a

detailed understanding of Butler's work as the next step is essential. (In part, however, the

detailed description of Butler's arguments that follows is necessary also to demonstrate the

extent to which Madonna embodies these arguments, which led the two to be connected in

the first place. Thus, one of the aims of this essay is to determine how much Madonna

contradicts Gender Trouble in relation to the extent to which she embodies it. Perhaps this will

enable us to decide whether we can hold up Madonna as a political icon, a queer

ambassador as it were, or whether she should be resigned to a passing (flawed) example of

the variable construction of identity).

Butler opens Gender Trouble with a description of the established gender ontology in which

the duality of sex (i.e. male-female) forms the basis of gender identity (masculine-feminine).

This ontology carries with it the 'invocation of a nonhistorical "before"' (1999:5), hence the

idea that the duality of sex, and the gendered characteristics that are said to mirror sex, are

contrived is not entertained. Butler continues that the unity of sex and gender in the binary

system is maintained by its oppositional nature. Society sets up 'the experience of a gendered

psychic disposition or cultural identity [as] an achievement'. Hence 'one is one's gender to the

extent that one is not the other gender' (ibid:29-30). Following this, the unity of sex and

gender (the male's masculinity and the female's femininity) are seen to necessitate

heterosexual desire - male and female desire 'therefore differentiates itself through an

oppositional relation to that other gender it desires' (ibid:30). A causal relationship is

established, therefore, between sex, gender and desire. As a result, anything that falls outside

these gender configurations is seen as pathological, hence the marginalization of the

'assertive female,' the 'effeminate man,' the 'lipstick lesbian,' and the 'macho gay' (Sawicki

1994:301). As assertiveness, [ef]feminacy, lipstick and machismo are all allocated as various

heterosexual constructs which are therefore seen to be appropriated in homosexual/queer

contexts, the assertive female et al are seen merely as 'chimerical representations of

originally heterosexual identities' (Butler 1999:41). Thus the original gender ontology is reified

and rationalized.

Butler proposes that if the gender sequences of man and woman are fictive constructs - that

is, 'socially instituted and maintained norms of intelligibility' - 'gender as a substance, the

viability of man and woman as nouns, is called into question by the dissonant play of

attributes that fail to conform to sequential or causal models of intelligibility' (ibid:23, 32). The

idea that gender is not a noun leads Butler to one of her most notable arguments - that

gender is performative. 'Gender is always a doing, though not a doing by a subject who might

be said to preexist the deed… There is no gender identity behind the expressions of gender;

that identity is performatively constituted by the very "expressions" that are said to be its

results' (ibid:33). (Butler here draws on Nietzsche's claim that 'there is no "being" behind

doing, effecting, becoming; "the doer" is merely a fiction added to the deed - the deed is

everything').

With these arguments, Butler opens up two central sites for the 'intervention, exposure, and

displacement of [binary masculine/feminine] reifications' (ibid:42). First, the idea of using

heterosexual constructs in non-heterosexual frames, Butler notes, 'brings into relief the utterly

constructed status of the so-called heterosexual original' (ibid:41). Thus the repeated

performance of 'queer' identities may eventually be 'normalised' and seen as 'culturally

intelligible'. Second, Butler points to the potential of gender parody as exemplified by the

practices of drag, cross-dressing and butch/femme identities. The performance of drag

emphasises the discontinuity between anatomy (of the performer) and gender (that is being

performed); it also exposes the illusion of gender identity as a fixed inner substance (ibid:175,

187). 'In imitating gender, drag implicitly reveals the imitative structure of gender itself - as

well as its contingency' (ibid:175). Further, this notion of gender parody does not assume it

imitates an original, rather the parody is of the very notion of the natural and the original: 'gay

is to straight not as copy is to original, but, rather, as copy is to copy' (ibid:175, 41). Thus

there is 'subversive laughter' 'in the realization that all along the original was derived'

(ibid:186, 176). The displacement in drag suggests a 'fluidity of identities' that is open to

resignification and recontextualisation (ibid:176). Related to this is the postmodern notion of

pastiche; Jameson asserts that it is 'without [parody's] satirical impulse, without laughter,

without that still latent feeling that there exists something normal compared to which what is

being imitated is rather comic' (1983:114). Butler is adamant that this does not undermine the

subversive potential of gender parody, but is another site from which notions of core/fixed

gender identities can be exposed as fictitious.

It is from these sites of variable and fluid identity construction, parody

and pastiche that Madonna can be seen to embody Butler's call to cause

gender trouble, at which we will now look in detail. A central element of

Madonna's sexual politics is female empowerment and the freedom to

express female sexuality. She communicates this by taking on a 'butch'

role in the sense that she reappropriates the mechanisms used to control

women (Skeggs 1993:67). Most notable is her anti-antiporn position; she

uses the currency of pornography to challenge the idea of women as

passive sex objects. For example in the Open Your Heart video, the woman is seen to

perform pornographic acts for the men who pay to peep through a small screen. Skeggs

notes how 'as their money runs out and the screen slowly closes they are shown contorting to

try and see through the last minute slit. They look pathetic, silly and desperate' (ibid:68).

Similarly, in The Blonde Ambition Tour, Madonna performed sexual acts on her male dancers,

taking the 'top' position which, in the traditional sense, is a male reserve. (ibid:68).

Madonna also rejects the self-monitoring of female sexuality by disrupting the 'male gaze'

whereby 'Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being

looked at' (Mulvey 1975; Berger 1972:47). Instead Madonna subjects men to the scrutiny of

her gaze, confronting the camera eye directly; 'looking at men is treated as something to be

blatant and positive about' instead of the usual case where 'women often avert their eyes in

modesty and submission to the gaze of the male audience' (Skeggs 1993:69; van Zoonen

1994:101). (Whereas traditionally dancing has been used to display the female body to men,

Madonna uses it to signify fun and self-indulgence. Hence the lyrics of Into the Groove: 'Only

when I'm dancin' do I feel this free'. 'Free' implies freedom from the male gaze; further dance

signifies power, energy and vitality, rather than passivity (Bradby 1994:85; Skeggs 1993:67)).

Hence Madonna claims "I can be a sex symbol, but I don't have to be a victim" (Robertson

1996:127).

Madonna is also seen to appropriate 'masculine' power through her notoriety for having

complete control over her career and image in a way that other female artists do not (Skeggs

1993:64; Robertson 1996:127). She also has a great deal of financial power - estimated at

around $200 million (Williams 1999:127) - thus she is perceived to be a shrewd

businesswoman.

The overt display of sexuality and the desire for control in women are typically labelled as

'whorish' and 'manipulative' by patriarchal narratives; Madonna throws such views back at

men by also emphasising what is 'female' in her. As Camille Paglia notes: 'Madonna is the

true feminist… Madonna has taught young women to be fully female and sexual while still

exercising control over their lives' (1990:39). Skeggs notes how she takes feminist issues of

domestic violence and emotional attachment seriously, 'express[ing] vulnerabilities and

celebrat[ing] strengths' (1993:65). Further, Madonna is not afraid to discuss her domestic side

and her role as a mother - it is not seen as an undermining of her capability for control. (In

Vanity Fair, she has recounted her domestic pleasure in picking lint from lint screens and

mating Sean [Penn]'s socks. More recently, she has become famous for her role as a mother

- and a good one at that. When asked: "What's been the most surprising thing about

motherhood?", she replied, "How much I could love something" (Hirschberg 1991:196-8;

William 1999:46)).

Madonna's appropriation of both 'male' and 'female' constructs supports Butler's idea of a

variable construction of identity. She takes this to the extreme by dressing in drag; in the

Express Yourself video, she wears a suit and monocle. At one point she teasingly opens and

closes the jacket to reveal a black lace bra, thus exposing gender as a 'put-on'

(Schwichtenberg 1993:135). Here, Madonna can be seen to mock male power and identity by

reducing gender and sex to the level of fashion and style (ibid:134).

More subversively, however, Madonna's parodic drag performances are

not limited to the appropriation of male style. Parker Tyler observes that:

'[Greta] Garbo "got in drag" whenever she took some heavy glamour

part, whenever she melted in or out of a man's arms, whenever she

simply let that heavenly-flexed neck… bear the weight of her thrown

back head… How resplendent seems the art of acting! It is all

impersonation, whether the sex underneath is true or not' (cited in Butler

1999:163). Madonna exposes femininity as a masquerade in her retrocinephiliac parodies of femme fatales such as Marilyn Monroe and Veronica Lake. In the

video for Material Girl, she imitates Monroe's "Diamonds are a Girl's Best Friend" number

from Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. The video reproduces the elements of blondness, sexuality

and gold-digging, but 'parodies the gold-digger's self-commodification as a form of 1980s

crass materialism: "The boy with the cold hard cash is always Mr. Right/ Cause we are living

in a material world, and I am a material girl"' (Robertson 1996:126). Madonna portrays a

'more savvy' Monroe in contrast to the traditional nostalgic treatment of her as a 'witless sex

object' (ibid:126). By manipulating the femme fatale image, Madonna demonstrates its

constructedness and performativity; further, simply by imitiating Monroe as one of a

succession of images in her career, Madonna mocks femininity as a 'meta-masquerade'.

Madonna's notorious image changes demonstrate what Butler referred to as the 'fluidity of

identity'. As part of these periodic style changes, Madonna dramatizes the discontinuity of

sex, gender and desire, particularly in Justify My Love, Truth or Dare and Sex. The Justify

video depicts Madonna in a sexual encounter with Tony Ward (a former gay porn model).

Later, other figures enter the scene, many are androgynous; one of them engages in an open

kiss with Madonna - it is difficult to tell whether it is male or female. Next we see two men

facing each other, and so Justify continues, 'alternately steamy and campy' (Henderson

1993:111). The polymorphism and ambiguity of these images blurs the boundaries

between sex, gender and desire, demonstrating that they are neither causal nor constant,

even within individuals.

A form of postmodern pastiche is recognizable in Justify My Love in that

Madonna borrows from gay subcultures - the record sleeve combines

gay male S&M imagery, Monroe features and a James Dean stance

(Skeggs 1993:71). In Vogue, she adopts the gay practice of vogueing,

which is prominent among African American and Latino gays, claiming "it

doesn't matter if you're black or white, if you're a boy or a girl", and that

anyone can "strike a pose, there's nothing to it". Combined with crossdressing images and retro-cinephilia, a camp-drag montage is created (Robertson 1996:1312). In this way, Madonna dissolves boundaries between gay subculture and mainstream

culture - thus you do not have to be gay to vogue, nor do you have to be straight to be a

femme fatale.

Indeed, it is Madonna's mainstream position in popular culture that facilitates her potential to

cause gender trouble (in a 1994 interview, Butler agreed that symbolic subversive politics is

tied to political practice through the role of the mass media (Osborne & Segal 1994)). Gay

journalist Don Baird writes that: 'Never has a pop star forced so many of the most basic and

necessary elements of gayness right into the face of this increasingly uptight nation with

power and finesse. Her message is clear - Get Over It - and she's the most popular woman in

the world who's talking up our good everything' (1991:33). Similarly, Carol Queen claims that

'The importance of Sex lies in its appearance in chain bookstores, its superstar creatrix, its

presence on the front page' (1993:151). Madonna seems to be a willing 'queer' supporter: she

has publicly aligned herself with gay politics being one of the first celebrities to perform in

AIDS benefits; biographies refer constantly to her close friendship with her gay dance teacher

Christopher Flynn; and she has jokingly refused to clarify he nature of her 'friendship' with

Sandra Bernhard (Robertson 1996:130-1).

It appears that Madonna's work mirrors Butler's vision of gender trouble very closely; the

examples outlined above provide a mere few of those that are available. Although the

evidence presents Madonna as a 'true feminist' and queer icon, a closer, more critical

analysis of her work reveals not only a number of factors undermining its subversive potential,

but also evidence that Madonna appropriates from sexual subcultures for her own ends rather

than for the ends of those from which she borrows. Moreover, there is reason to believe much

of her work is not subversive at all.

A central obstacle to the subversive potential of Madonna's work is that its audience may not

read it in the way they are intended to. Brown & Schulze found much variation in the way

students interpreted the videos to Papa Don't Preach and Open Your Heart; for example, the

pornography in Open (see above) led Madonna to be perceived by some as 'a classic object

of male desire' rather than demonstrating 'an escape from a patriarchal construction of

woman as "something to be looked at"' (1990:100, 97). Robertson notes how 'jewellery

thieves in… Resevoir Dogs argue if Like A Virgin is about "big dick" or female desire'

(1996:118). This signals either an unwillingness or inability of society to embrace the idea of

female sexuality; this is not restricted to men either - even Madonna's young female fans

describe her as 'tarty' (Bradby 1994:79). It seems patriarchal discourses embedded in society

reduce Madonna's sexual expression to prostitution - that is, a threat to society. Another

danger is that her parodic presentations of femme fatales are not read ironically; if this is the

case, all that is left is the makeup, high-heels and long hair, reinforcing the idea that women's

only purpose in life is to serve men. Thus despite her good intentions, Kaplan says we need

to decide 'if Madonna subverts the patriarchal feminine by unmasking it or whether she

ultimately reinscribes [it] by allowing her body to be recuperated for voyerism' (1993:156).

Clearly, overlooking the intended meaning of Madonna's work is an

obstacle; more fundamentally problematical, however, is the

contention that Justify My Love et al are not subversive at all. An

article in the New Yorker (February 1993) claims that: 'Camp is dead…gender tripping can't

be subversive anymore' because Madonna 'has opened all the closets, turning deviance into

a theme park' (in Robertson 1996:118). The 'heterosexualisation' of camp by popular culture

has led to a 'watering down' of its 'critical and political edge' (ibid:122). To make camp

culturally intelligible it has had to be mainstreamed - but Butler's notion that there is no

original implies that there should be no 'mainstream', every sex-gender-desire configuration

needs to be regarded on equal terms. This is not really something we can blame Madonna

for, but we do need to be aware of the restriction it places on her ability to subvert. Madonna's

heterosexualisation of camp suggests that her work may not be as 'queer' as it seems. For

example, one image in Sex 'seems to be designed to mark [Madonna] off from… the

[lesbians] in that scene… it's more like lesbians having sex together with Madonna along for

the ride' (Crimp & Warner 1993:109). Hence, 'she can be as queer as she wants to be, but

only because we know she's not' (ibid:95).

This 'superficial' queerness relates to accusations that Madonna uses her sexuality, changing

image and 'controversial' sex politics as mere fuel for publicity. Hooks claims that she 'publicly

name[s her]… appropriation of black culture as yet another sign of [her] radical chic'

(1992:157). Similarly with queer appropriation, 'the gay men in [Sex] seem to be there more

as suppliers of sexual glamour than actual sexual partners… It's more about their exotic

appeal… than it is about gay sex' (Crimp & Warner 1993:97). Similarly, rather than a variable

construction of identity, Madonna's changing image is seen as consumer-interest driven.

Millman describes her as 'the video generation's Barbie' (1993:53). 'Like Barbie, Madonna

sells because, like Mattel, she constantly updates the model - Boy Toy Madonna, Material Girl

Madonna, Thin Madonna, Madonna in Drag, S&M Madonna, and so on' (Robertson

1996:123).

Of course, only Madonna (and her marketers?) know[s] the real reason for her various styles.

Either way, however, because of her privileged social position, Madonna's appropriations are

unable to do justice to the subcultures from which she borrows. Hooks asserts it is 'a sign of

white privilege to be able to "see"… black culture… [it] enables one to ignore white

supremacist domination and the hurt it inflicts…when [Madonna attempts] to imitate… the

"essence" of soul and blackness, [her] cultural productions…have an air of sham' (1992:158).

Again, in gay subculture 'in ignoring real difference ("it doesn't matter"), Madonna's Vogue

denies real antagonisms and real struggles', thus 'no matter how well intentioned, can never

be more than a form of subcultural tourism at the level of style' (Robertson 1996:133, 135).

Hence, for those who are not superstars, Madonna's appropriations are unattainable escapist

fantasies. In response to Madonna saying "A lot of people are afraid to say what they want

and so they don't get what they want", Martin Amis sarcastically points out that 'the book

[Sex], remember, is… fantasy, a realm in which it is presumably okay to get what you, even if

it's your sister, or your dog' (1993:260)!

Although Madonna's work aligns itself with Butler's feminist/queer political strategy, to say

Madonna embodies Gender Trouble is clearly Utopian. This does not mean we should

overlook her attempts completely, for the messages that much of society appear to be

oblivious to can still be used to illustrate subversion. Nevertheless, so far, the association

between Madonna and Gender Trouble is more of an academic observation than a queer

revolution.