Lesson 8-3 Sin, Suffering and Redemption

advertisement

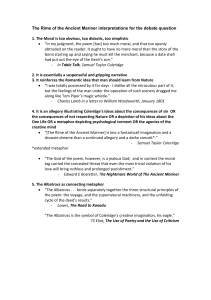

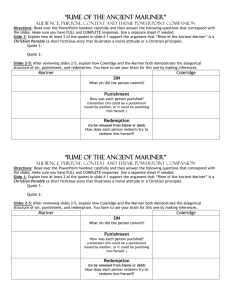

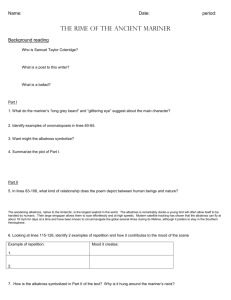

CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge Samuel Taylor Coleridge Peter Vandyke (1795) National Portrait Gallery, London Samuel Taylor Coleridge Patrick Proctor (1976) Redfern Gallery, London Overview: When William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge published Lyrical Ballads in 1798, they conceived of their tasks quite differently. As Coleridge later recorded in his Biographia Literaria, Wordsworth would contribute poems depicting “ordinary life,” while he (Coleridge) would depict “supernatural” incidents. Coleridge’s interest in the supernatural is exemplified in “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” which was the opening poem in Lyrical Ballads. It is a narrative poem in which a Mariner (sailing with a crew of 200 men) kills a bird: an innocent Albatross, which befriends the seamen as they are locked in ice at the South Pole. The Mariner’s act has no clear provocation: he has no identifiable motive. Still, his act is a sin: he is needlessly aggressive; he disrupts the naturally-created order; and he disregards God’s exhortation to love all creatures in the world. The implications of the Mariner’s act are severe, and punishment comes swiftly, primarily from the spirit world. Many of the subsequent events are beyond believability, but Coleridge asks us to engage in a “willing suspension of disbelief” (as he writes in Biographia Literaria). The question for readers (and the Ancient Mariner’s listeners) is not whether or not the magical elements are real but what they mean. Coleridge asserts the reality of the spirit world and the importance of being receptive to it. This, more than a scientific, mechanic mind, constitutes the fullness of human existence. As the poem unfolds, we find how deeply it is rooted in Christianity: Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 1 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) the primary biblical sources for Coleridge’s ideas, and the archetypal Christian pattern that the poem enacts, of sin, suffering, and redemption. As readers, our task is to determine what Coleridge does, creatively, with that Christian foundation for the poem. Objectives: To study a longer poem, which addresses the archetypal Christian journey of sin, suffering, penance, and redemption To consider to what extent the Mariner’s voyage and his life after it fit that pattern To identify the poem as a ballad and to evaluate its suitability for the subject Readings: “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” (1798 – 1817) http://www.wordsworth.org.uk/poetry/index.asp?pageid=154 8.3.1. Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772 – 1834) As the two portraits (above) suggest, Samuel Taylor Coleridge—STC, as he called himself— was a divided man. On the one hand, his life was filled with joy, particularly in his early years. He was a gifted intellectual, with wide-ranging interests in literature, theology and philosophy, which he studied at Cambridge University and in Germany. He was a marvelous talker, able to enchant the audiences for his lectures and poetry readings. As an enthusiastic (and the first serious) mountaineer in the Lake District, he also pursued vigorous outdoor activities with delight, deriving creative inspiration from the inclement weather and great heights that he scaled. As well, his life was enriched immeasurably by his friendship with William Wordsworth, which began in 1795, the date of the portrait at the top. On the other hand, Coleridge led a deeply troubled life. His marriage was an unhappy one, and he fell deeply in love with another woman (Wordsworth’s sister-in-law), a relationship that could not be consummated. He suffered from countless physical ailments, which were treated with opium (a standard painkiller at the time), which led to a crippling addition to the drug. As well, his mind, while capacious, was inconsistently creative, which meant that portions of his intellectual and, especially, his literary life were devastatingly unproductive. In 1803, he left England to travel aimlessly in the Mediterranean, leaving behind a marriage in ruins and a fractured friendship with the Wordsworths, not settling again until 1816 (in London). “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” which he composed in its first version in 1798, the anus mirabilis in his poetic friendship with Wordsworth, was revised continuously until 1817, the version we are reading. Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 2 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Some would say that Coleridge became increasingly like the Mariner—lonely, unhappy, homeless, and plagued by guilt and shame. The two portraits above nicely reflect this dividedness: Proctor’s is clearly a deliberate echo of Vandyke’s, with a difference. Vandyke’s portrait, amply lit, shows a young man of blossoming potential and prosperity, while Proctor’s painting, considerably darkened, foresees the troubling elements that will come to plague Coleridge as his life unfolds: the eyes are narrower, the mouth is closed, the hair is unkempt, the skin is dark, and the face is lined with sharper shadows. As you read “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” notice that same duality: the young Mariner departs with his crew, confident and in command of the swiftly-moving journey to exotic, unexplored destinations; quickly, however, the departing ease and merriment turn to trouble, when a sinful act is committed and extraordinary punishment follows. Coleridge knew well the turn in human circumstances from joy to sadness (and light to dark, as the two portraits suggest). In fact, he suggests that one’s life is superficial and incomplete without profound suffering, which awakens one to the dark forces that operate in the universe and deepens human experience. This illustration of the Ancient Mariner, by Sven Berlin (1997), illustrates both aspects: one eye sparkles and radiates with light, signifying his magical gift as a storyteller, even in his “ancient” age, while the tearful eye expresses the immense sadness and suffering that underlies the tale that he continually recounts. Sven Berlin, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Somerset: Odyssey, 1997. Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 3 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) 8.3.2. Coleridge’s Sources The poem is long and extraordinary in its scope. Coleridge’s capacious, intellectual mind is at work in his composition. His sources are numerous. Cain and Abel: Genesis 4 (1-16) The poem developed out of Coleridge’s deep thinking about evil: both its origins (what causes evil acts) and the human condition of living in sin. He turned to the Old Testament story of Cain and Abel. Read that account and keep it in mind as you follow the narrative in the poem. Notice, especially, in relation to the poem, how Cain’s murder of his innocent brother is entirely unjustified (like the Mariner’s shooting of the friendly Albatross), and how his punishment is specifically to wander away from home, his fields now bloodied by his act (as the Ancient Mariner must wander across the earth, alone and in penance). Also, both Cain and the Mariner are “marked” on their bodies, in some way, so that all will know who they are. Imaginatively, Coleridge sought to probe the condition of suffering in a state of sin, which he does by creating the fictional Mariner, modeled in many ways on Cain. The poem goes beyond the biblical account of Cain in taking us inside the mind, body, and heart of the suffering Mariner, whose torment almost exceeds our comprehension. Published Travel Accounts The Mariner and his crew set out on an extraordinary journey: they travel swiftly through the Atlantic Ocean from (presumably) England to cross the equator and arrive at the South Pole (Part 1), after which they travel north again, in the Pacific waters, when the ship falls into stillness at the equator again. The rest of the journey is more vaguely sketched out, in geographical terms, but we can presume that it likely crossed the Indian Ocean, dipped south of Africa, and then returned home via the Atlantic Ocean again. Coleridge did not travel this distance himself, but he read numerous travel accounts of great expeditions, which gave him images that he incorporated into the poem, including the appearance and crackling sounds of the ice, the phosphorescent effects of stagnant waters, and the features of the Albatross. That geographical factuality is blended with the mythic scope of the Cain story. Slave Narratives Coleridge was among many poets, during the Romantic period, who supported the Abolitionist campaign: a movement to urge the British Parliament to end its involvement in the Atlantic Slave Trade. Britain’s role in the “triangular trade,” whereby West Africans were captured, transported to the West Indies, and forced to work as slaves on sugar, tea, and cotton plantations, was at its peak in the late eighteenth century. A wide ranging Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 4 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) movement to abolish this atrocious treatment of fellow human beings—in an era when democratic rights, the impulse behind the French Revolution, were being trumped, included, very importantly, literary figures who were invited to write works that could sway public opinion. Coleridge delivered anti-slavery lectures in Bristol, one of the chief ports in the trade, in support of the campaign. The rising scrutiny of all aspects of the Slave Trade, during this era, including careful observation of the inadequacies of the passenger ships and record keeping of the slaves’ ordeals at sea, may underpin the poem, particularly the oceanic journey, deaths of the crew, and final disintegration of the ship itself. 8.3.3. Poetic Form Ballad: The poem is a ballad: it is narrative (tells a story); proceeds through dialogue (in this case, a story is told); follows a series of momentous, dramatic incidents; incorporates supernatural elements; and is highly musical. The stanza form is set: a quatrain with an a b c b rhyme scheme, and a metre that alternates from 4 beats (iambic tetrametre) to three beats (iambic trimetre). Read the following stanza out loud to hear both the rhyme and the metre. Notice that this musicality suits the narrative momentum of the poem: while the musical sounds tumble forward, so to speak, with a tripping pattern of sounds, which flow lightly and quickly, the events in the story happen swiftly and decisively. Sin, Coleridge suggests (as Dante’s Inferno does, too), slips into the soul remarkably easily, and the punishment and suffering that follow are immediate. 8.3.4 Ballad Stanza He holds him with his glittering eye— The wedding-guest stood still, And listens like a three years child: The Mariner hath his will. a b c b 4 iambs 3 iambs 4 iambs 3 iambs Frame Narrative: Equally important is the frame narrative, which situates a story within a story, like a painting within a frame. The outer story (the frame) is the present tense: the old Mariner is living out his penance, arduously and eternally. In that present life, he must retell his tale continuously, reliving his painful experience and seeking to reform his listeners who, by hearing of the terrible possibilities of sin, will mend their own ways. The Ancient Mariner suffers bodily pain if he fails to retell his tale over and over. The inner story (the picture inside the frame) is the journey itself, roughly 50 years earlier. He recalls every incident l in such detail that readers, at times, forget that it is just a story, and not the real event. In fact, Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 5 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) the inner story dominates, while the frame is given less space in the poem. The reader must ask two questions about a frame narrative: Why is the inner story, the event from the past, looming so large in the character’s mind in the present? Why has it not disappeared from his memory? Why is it, in some ways, bigger than the “frame” (the present), as a painting draws a viewer’s attention far more than the frame does? At what point in the narrative does the frame interrupt the telling of the inner story and why? The listener in the poem is a Wedding Guest, who has been detained from the celebration by the Ancient Mariner to hear the tale. Throughout the poem, he intervenes, at certain crucial moments. Why does he intrude? Does he experience disbelief when the story delves into extreme and extraordinary human experiences? Is the Wedding Guest, like us, struggling to believe what is beyond our comprehension? When the Ancient Mariner reassures him of the truth of the tale, are we asked, too, to “suspend our disbelief” (in Coleridge’s words). In other words, we must enter the world of sin and suffering with openness to the truth of the circumstances; a frame narrative gives the Ancient Mariner’s listeners, and all of us as readers, a proximity to the events through the frame. Mario Prassinos, La Ballade du Vieux Marin. Paris: GLM, 1946. Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 6 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) 8.3.5. Supernaturalism Think of the many supernatural elements in the poem: The Polar Spirit, deep under the water, who follows the ship, in vengeance, as it turns north The spectre ship, which approaches the Mariner’s boat without a wind The two figures in the ship: Death and Life-in-Death, who throw the dice to determine the separate fates of the Mariner and of the crew The souls of the dead crew members, which visibly leave their bodies The two Spirit voices, who discuss the Mariner’s lifelong penance The violent disintegration of the ship, as it mysteriously capsizes underwater near the final harbour The Ancient Mariner himself, who survives the journey and endures his old age in a ghostly form, traveling at night from land to land like a spirit Coleridge asks that we accept all of these elements as real. The question we must ask is not whether they exist but what they mean. Again, we must “suspend our disbelief.” Witnessing the real effects of supernatural elements on the characters in the poem—we see their changing circumstances—is evidence of their reality and their power. The poem, in other words, is not about distortion in the Mariner’s mind, as he undergoes guilt, extreme deprivation, and unthinkable suffering; his mind is not, under these extremes, just hallucinating in a fanciful, illusory way. Rather, Coleridge presents the more terrifying view that what the Ancient Mariner relates is true. As you read the poem, think about whether or not good spirits are present, as well. Does God have a presence in the poem? What about angels? Does a good spiritual force enable the Mariner’s partial redemption? Is the beauty of God’s creation still found, on this journey, in spite of the overwhelming misery? Reading: “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” (1798 – 1817) http://www.wordsworth.org.uk/poetry/index.asp?pageid=154 Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 7 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) 8.3.6. Literary Analysis and Study Questions Part the First Frame: The frame is quite pronounced as the poem opens. Whom has the Mariner stopped as his next listener? Why is it significant that he is a Wedding Guest? What merriment is near at hand and surely more inviting, for him, than the haunting appearance of the old Mariner? How does the Ancient Mariner hold the attention of the young man: is the story somewhat magical, causing the Wedding Guest to be spellbound by it? Why is the contrast between the two men important? Narrative (the Ancient Mariner’s tale): What happens? How does the journey begin and unfold? Notice the immense compression: geographically (from England to the South Pole); Gustave Doré, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. atmospherically (from equatorial London: Doré Gallery, 1876. heat to polar ice); socially (from human community present at the wedding, in the frame, to a remote region where no humans exist, in the actual journey); temporally (the present tense of the frame to the distant past of the voyage); and morally (from goodness to sin). Look carefully at how the Albatross is described. Why is it white? Is it significant that it befriends the crew, hovering near the ship each day? In turn, how do the crew befriend it? Is the bird a symbol? If so, of what? Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 8 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Patrick Proctor, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. London: Editions Alecto, 1978. Part 1 ends with the central act: the crux of the whole poem. The Mariner shoots the (good) bird. Read the final stanza carefully, and notice the interruption from the Wedding Guest, at this point, in response to the ghastly look on the Ancient Mariner’s face as he recalls the event. o What causes the act? Why is it stated so simply and without explanation or reflection? Did anything provoke the Mariner? Does the Ancient Mariner, himself, know why he kills the bird, even after all of these years of telling his tale? Is Coleridge suggesting that the origin of sin is inexplicable, as a deeply mysterious force? (Do we fully understand Cain’s murder of his brother Abel? Does Cain understand?) Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 9 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) o What is the crime? While the origin of this sin is left unexplained, the crime itself is quite clear. What has the young Mariner done wrong? Is he asserting dominance over the natural world, in a destructive way? Is he rejecting and breaking a relationship with nature? Does this indicate selfishness: that human beings cannot co-exist with other living things? God asks that all beings in Creation be respected. Is it a rejection of the hospitality that the bird offered, in a hostile region, and an end to the hospitality that the crew were offering to the bird? Christians are asked to welcome pilgrims (strangers), with kindness and generosity. Is it an anti-social act, done in aggression, without consultation with the crew? Does it break social community and love? Look carefully at Gustave Doré’s illustration (below) . Why is the Mariner himself absent from the image? In the second illustration, by Mervyn Peake (1943), the Mariner is absent, again, although we do see a group of diminished crew members. Why have the artists omitted the Mariner? Notice, too, how the bird is portrayed in both images: it is a living being, gracefully in flight, dominating the sky. Does that beautiful image deepen our sense of the Mariner’s outrageous act? Why does Peake present the arrow piercing the body of the bird, leaving it limp and emitting a cry of pain? Is the bird being crucified (like Christ)? Is the whole cosmic order, suggested by the celestial circles around and beneath it, now disordered? Why are Peake’s icebergs so sharp and geometric, in contrast to the undulating, pulsating body of the organic bird? Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 10 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Gustave Doré, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. London: Doré Gallery, 1876. Mervyn Peake, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. London: Chatto and Windus, 1943. Part the Second Frame: Does it interrupt the narrative? If not, why not? Narrative: While the origin of the crime is not clear, as we discussed above, the implications of its seriousness are swift and severe. Coleridge suggests that the spiritual world seeks vengeance: a polar spirit follows the ship “and plagued us so” (132). o How do the crewmembers suffer? Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 11 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Why is the ship stagnant and still (in contrast to the initial unhindered swiftness of movement going south)? How does that stillness affect time (“day after day, day after day”)? What unbearable heat do they endure? Notice the very expressive colour words: “copper” and “bloody”. These colours are unnatural and extreme; they suggest that natural phenomena are thrown out of order by the Mariner’s act. Consider these possible biblical allusions. Deuteronomy 28: 15, 23 (Warnings Against Disobedience) But if you will not obey the Lord your God by diligently observing his commandments and decrees, . . . then all of these curses shall come upon you and overtake you. The sky over your head shall be bronze, and the earth under you iron. Joel 2: 30-31 (God’s Spirit Poured Out) I will show portents in the heavens and on the earth. . . .The Sun shall be turned to darkness, and the moon to blood, before the great and terrible day of the Lord comes. Patrick Proctor What extreme thirst do the crew members experience? Why is that ironic? Water, water, everywhere, And all the boards did shrink; Water, water everywhere, Nor any drop to drink. Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 12 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Without water, the throat dries up and speech is impossible. Is lack of meaningful communication another aspect of their suffering? Does it cause isolation and a broken community (in the same way that the Mariner’s arrow breaks the human relationship with nature)? Coleridge conceived of unity in the universe, which he called the One Life: like a breeze that touches and infiltrates everything, the One Life, for Coleridge, is a divine force that unites and harmonizes all aspects of Creation, infusing everything with spirituality. Conversation and social bonds are part of that vast, interconnected oneness: “one intellectual breeze” that “sweeps” over everything (as he writes in “The Eolian Harp,” an instrument enacts, through its music, the “Rhythm in all”). The mariners also suffer from a loss of beauty in their surroundings (at least, as they perceive them). The beauty of the Albatross and the crackling, glistening cliffs of ice are gone; instead, they are surrounded by “slimy things” and a “slimy sea.” Even the colours of the “death fires” that dance on the water—an accurate, phosphorescent effect—occur because the water is hot and stagnant. Coleridge conceived of human fulfillment and goodness as arising from a “heart / Awake to Love and Beauty!” (as he states in “This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison). Its absence leads to dejection. Mervyn Peake o Part the Second concludes with the Albatross, as Part the First did. The Mariner is not allowed to forget his act. Now, the bird is hung around his neck, replacing his cross. What is the significance of that act? What is the Christian allusion here? Here, again, we have to “suspend our disbelief”: the bird is far too large and weighty to be hung around his neck. Still, we are asked to imagine its Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 13 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) grotesque proximity to the Mariner: he broke the bond with nature; now, the bond is restored (the bird is “hung” right on him) but in a perverse way, as he must now carry a dead bird on his body. The punishment replicates the sin, much like Dante’s use of contrapasso in Inferno. Part the Third Narrative o First, the misery and deprivation continue and deepen in severity. Notice, throughout the poem, how Coleridge uses repetition of words effectively. In the first stanza, “weary” is repeated four times. This gives the poem musicality, but it also emphasizes the mariners’ condition: physically and psychologically they are exhausted. Even their eyes are “glazed” now, which further deprives them of the potential to communicate. Their “unslack’d” throats are completely dry: “through utter drought all dumb we stood!” Drought suggests, too, a spiritual dryness. Think about the word “agape” (163). Literally, it means their mouths are gaping, or open. Agape, pronounced differently, is also a Christian word. What does it mean? What is its significance in this context? In desperation, a gesture of savagery occurs: the Mariner sucks his own blood in order to speak. o Then, the prospect of rescue arises. Ironically, however, it arrives as a punitive force, in the form of two spectral figures, who travel in a ship that has no sails and moves supernaturally without a breeze. Doré’s composition, with its triangular formation of hopeful figures, is fittingly ironic, for their hope is misplaced. Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 14 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Gustave Dore Gustave Doré Herbert Cole, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. London: Gay & Bird, 1900. o How is the spectre ship described? Why does the setting sun “peer” through its “ribs” creating the image of a “dungeon-grate”? Do the “ribs” belong to the ship or to the two skeletal figures on board, or both? Why does it approach at sunset? Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 15 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Mario Prassinos o The two figures, Life-in-Death and Death, are casting dice to determine the fate of the Mariner and his crew: she wins the Mariner, and he wins the crew, who die instantly, while the Mariner lives on (in a death-like state), with 200 dead men at his feet. The casting of dice seems callous in its randomness, and contrary to our conception of an ordered world. We would hope that the outcome of human lives is determined by a divine force that is greater and more meaningful than a chance event: a game. Perhaps, Coleridge is, again, reinforcing the loss of order and meaning in the world, as if the Mariner’s act reverberated throughout the universe, disturbing all aspects of cosmic harmony and goodness. Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 16 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Gustave Doré Patrick Proctor This is also a supernatural event. We have trouble comprehending its believability, wondering if it might be a fanciful illusion in the Mariner’s distorted mind—the psychological effects of his deprivation. However, Coleridge wants us to accept the reality of the event. It has observable effects: the crew dies and the Mariner lives, in a deathly way. The effects of sin are concrete and palpable. Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 17 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Mervyn Peake Part the Fourth This section is the structural centre of the poem (the fourth of its seven parts). The narrative should pivot, at this point, which it does. Frame: In stanza one, the Wedding Guest interrupts. Why now? Does he, like us, wonder how the Mariner survived? Is he a ghost? How does the Ancient Mariner respond? Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 18 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Narrative: First, again, the suffering deepens. The surroundings are unendurably ugly: a “rotting sea” with “a thousand thousand slimy things.” The “drought” is indeed a spiritual one. The Mariner is unable to pray, which severs his relationship with God and with saints. He closes his eyes, in complete solitariness. His solitude is extreme (note, again, the repetition of words): Alone, alone, all, all alone Alone on a wide, wide sea! And never a saint took pity on My soul in agony. Patrick Proctor Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 Gustave Doré 19 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Then, change occurs. Indeed, the Mariner must look beyond his self “pity,” which he does. The motive for this is unclear (like the mysterious nature of his crime), but the sequence of alterations in his behaviour is clear. Perhaps, a good Spirit is supernaturally slipping into his soul, alongside the dark Spirits that have instigated the many aspects of his suffering. He sees the beauty of the Moon and stars in the sky, intuiting, too, that they have a rightful place in the universe, a home, so to speak, which he yearns for too. A rightful order—not just dark, chaotic forces—does exist. He then perceives the white moonlight as “Like April hoar-frost spread” on the water, a simile that indicates the return of his imagination: seeing things other than they really are. Seeing and imagining that beauty leads to a new perception of the “slimy things,” which are now, to him, beautifully coloured and vivaciously active sea snakes. They are lively—the only living things near him—and “happy.” Very significantly, he feels love for them and blesses them; his spiritual “drought” has become a gushing “spring,” as he abides by God’s exhortation to respect all living creatures, even the smallest, most insignificant ones. Finally, he is able to pray. The Albatross, in this moment, falls off. We can see the archetypal Christian pattern taking shape: sin brings suffering and penance, which is forgiven by God, who mercifully forgives and brings redemption to sinners. The Albatross’s fall into the water signifies a certain release from the sin. The Mariner’s conditions improve considerably; however, he is never fully redeemed, and the rest of the journey is mixed with both joy and continued horror. Parts the Fifth and Sixth Narrative: Trace, carefully, the unevenness of the Mariner’s subsequent journey: it is neither wholly punitive (as it was) or wholly redemptive (as he hopes it will be). Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 20 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Part the Fifth He is, in numerous ways, abundantly restored through sleep rain fresh, moving air angelic spirits sweet sounds (from birds) and imagination (recollections of home) Alexander Calder, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. New York: Reynell and Hitchcock, 1946. He is also horrified by the groaning and stirring of the dead men, who rise up and begin to steer the ship, as a silent, “ghastly” crew Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 21 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Part the Sixth As the ship nears the harbour, the Mariner is further restored: “Oh! dream of joy!” he shouts, as he sees the familiar coastal landmarks. We can feel his extraordinary relief. The harbour bay, too, approached in moonlight, is quite beautiful, in a somber way. Fittingly, it lacks the bright light and cheerfulness of the departure, for the Mariner is now a profoundly changed man; instead, it is quietly and serenely beautiful, with its soften colours and light. As well, the “seraph-band” (the highest order of angels) lighting the ship, serve as a signal to the three passengers of a nearby boat. One of them is a holy Hermit, whom the Mariner hopes will “shrieve my soul.” However, the deprivation is ongoing, as Part the Seventh makes clear: The Hermit does not absolve him of his sin; instead, he becomes his first listener, as the journey is recounted (and relived) even as the Mariner is just arriving “home.” Horrifically, the Mariner’s ship, disintegrates, as turbulent waters rumble up beneath it. The Mariner is saved by the Pilot’s boat, but his emaciated, ghostly appearance is terrifying, which signals the strangeness and aloneness that he will endure eternally. Part the Seventh Narrative: The Mariner explains his ongoing penance: the bodily “agony” that overcomes him until he begins his tale anew. He passes at night, from land to land, seeking the listener “that must hear me”—a person, that is, who will be reformed, morally, by hearing the story. Frame: The frame returns prominently, now. The Wedding Guest is one of a long line of listeners, who have followed the Hermit. What specific advice does the Ancient Mariner give? Why does he disappear quickly? What is the Wedding Guest’s response? Does he go to the wedding? If not, why not? Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 22 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) Narrative and Frame: We see, now, how the two components are intertwined. The end of the tale is always its beginning. This listener is just one of many; the Mariner’s relief, at the story’s end, is just temporary. The poem, then, is circular: once finished, it immediately begins again. The Ancient Mariner is, indeed, imprisoned by his past. Mervyn Peake Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 23 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) 8.3.13 Activity for Blackboard Discussion: Three Questions o Is it right that the Ancient Mariner receives partial redemption for his suffering but is never fully redeemed? Is his ongoing penance justified? o Coleridge was very Christian, well-read in theology and the Bible. However, he was not, in post-Reformation England, a Catholic man. Is it useful for us to read this poem? Does it illuminate anything about Catholicism? o Look at the painting below by Patrick Proctor. He alters the end of the poem by creating an image of eternal journeying on water, rather than the “land” that Coleridge specifies. Is that appropriate? Does the image still suggest a certain imprisonment, with the deck posts standing in for the mesh of trees that might entangle the Ancient Mariner on land, in the darkness (as Doré portrays). Are both the posts and the trees suggesting, too, that the old man is imprisoned by his past and his tale? Is that same idea expressed by André Lhote, in the design of his book cover for his illustrated edition of the poem? A net like fibre is wrapped around the entire book itself. It looks somewhat like fishing net. Why has the artist done that? Does it illuminate a central aspect of the poem? Patrick Proctor Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 Gustave Doré 24 CATH 330.66 – Catholicism and the Arts Module Eight – The Romantic Period (1700-1832) André Lhote Lesson 8.3 – Sin, Suffering and Redemption: S. T. Coleridge ©Continuing & Distance Education, St. Francis Xavier University - 2012 25