Private Finance Initiative and Public Private Partnerships

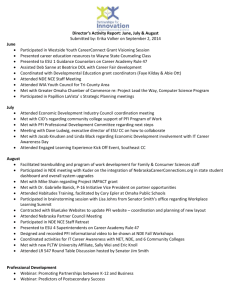

advertisement