Recruitment and propaganda.doc

Recruitment, propaganda and censorship

Recruitment

Britain:

Britain began the war with a very small army, and it was soon realised that a mass recruitment drive was necessary. From August 1914, rallies were held, speeches made, and newspaper articles published imploring men to join up. Men were recruited in factories, theatres, universities and churches – even at football matches. The main factor motivating enlistment at this time was patriotic fervour, and by the end of 1914 a further 500,000 men been recruited.

In November 1914, the British government introduced the Derby scheme, under which the

'Pals' battalions were created. Units would be recruited from one town, factory or club, enabling friends to fight together in the war. Many of these units were wiped out during the

Battle of the Somme in 1916.

When it became clear that the Derby scheme was not going to produce enough recruits to replace those being killed and wounded in France and Belgium, the government introduced the Military Service Act in January 1916. This gave it the power to conscript all unmarried men between the ages of 18 and 41, and direct them to either military or labour service. In

May of that year, the Act was extended to cover married men as well. Under the Act, conscientious objectors were excluded from front line fighting, but were expected to serve in non-combat roles. Those who objected to any participation in the war whatever, were imprisoned and subjected to harsh treatment; about 70 died. Apart from the conscientious objectors, there was little opposition to the introduction of conscription.

Germany:

Germany already had conscription in 1914. Every male between 17 and 45 was required to do military service, and these reserves were quickly mobilised when war broke out.

The National Service Law was introduced in December 1916, to give the Ministry for War control over all males between the ages of 17 and 60. Conscription was stepped up, enabling the government to bring nine million men into the army.

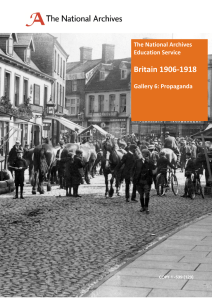

Propaganda and censorship

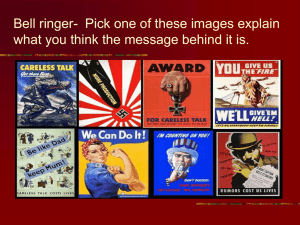

All the nations that participated in the war used propaganda to whip up support for the conflict and to imbue their people with a hatred of the enemy. The most successful propaganda was based on some fact rather than pure fiction.

Positive propaganda appealed to people’s patriotism and sense of duty, in order to persuade them to support the war effort.

Negative propaganda appealed to people’s baser instincts – presenting the enemy as monsters, or shaming people into joining up.

Britain:

Britain had a propaganda advantage over Germany for all of the war, due to the German decision to commit a series of 'atrocities' such as the 'rape of Belgium' and the use of unrestricted submarine warfare (particular the sinking of the Lusitania ).

Germans were depicted as subhuman monsters, killing innocent women and children. The

Kaiser was depicted as the symbol of evil in the world.

Initially, British propaganda (mainly posters and cartoons) was mostly produced by patriotic newspaper publishers. However, as the war progressed, a War Propaganda Bureau was established to coordinate propaganda campaigns.

In April 1915, the Directorate of Special Intelligence was established to coordinate censorship of materials deemed to harm the war effort.

Letters from the trenches were censored, but many soldiers managed to by-pass the censorship process. Similarly, soldiers were forbidden from keeping diaries, but many got around this directive.

Germany:

While similar in style to its British counterpart, German propaganda was less well organised and far less effective. The enemy was presented as trying to deny Germany her position of greatness, but the Germans were unable to galvanise public opinion through depictions of

Allied atrocities. There was no central department coordinating the German propaganda effort.

German censorship was very effective, however. It was very difficult for Germans to get a true picture of what was happening at the front.