Marias Massacre

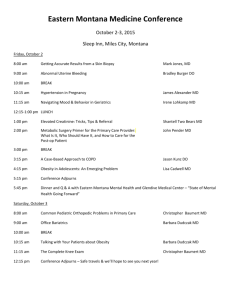

advertisement

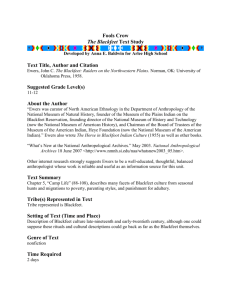

Fools Crow Marias Massacre Developed by Anna E. Baldwin for Arlee High School Text Title, Author and Citation To be used with Fools Crow by James Welch. Suggested Grade Level(s) 11-12 Tribe(s) Represented in Study Tribe represented is Blackfeet. Time Required 2 days Supplies and Materials Copies of the websites listed under Resources and References. Genre of Text nonfiction Implementation Level, Essential Understandings and MT Content Standards Banks - O’meter Essential Understandings – Big Ideas 1-Diversity between tribal x groups is great. 5-History represents subjective experience & perspective. 4 Social Action 3 Transformative 2 Additive x 3-Oral histories are valid & predate European contact. 7-Tribes reserved a portion of their land-base through treaties. 1 Contributions x 4-Ideologies, traditions, beliefs, & spirituality persist 8-Three forms of sovereignty exist – federal, state, & tribal. 2-Diversity between individuals is great. x Essential Understandings Reading 1.2, 2.2, 4.2 Social Studies 1.2, 2.6, 4.7 6-Federal Indian policies shifted through 7 major periods. Instructional Outcomes – Learning Targets Content Area Standards Montana Content Standards Science Other(s) Literature 1.1, 1.5, 1.6, 3.2, 4.1, 4.2 Essential Understanding 1: There is great diversity among the 12 tribal Nations of Montana in their languages, cultures, histories and governments. Each Nation has a distinct and unique cultural heritage that contributes to modern Montana. Essential Understanding 3: The ideologies of Native traditional beliefs and spirituality persist into modern day life as tribal cultures, traditions and languages are still practiced by many American Indian people and are incorporated into how tribes govern and manage their affairs. Additionally, each tribe has its own oral history beginning with their origins that are as valid as written histories. These histories pre-date the “discovery” of North America. Essential Understanding 6: There were many federal policies put into place throughout American history that have impacted Indian people and shape who they are today. Much of Indian history can be related through several major federal policy periods: Colonization Period, Treaty Period, Allotment Period, Boarding School Period, Tribal Reorganization, Termination, Self-determination. Social Studies Students will 1.2 apply criteria to evaluate information (e.g., origin, authority, accuracy, bias, and distortion of information and ideas). 2.6 analyze and evaluate conditions, actions and motivations that contribute to conflict and cooperation within and among groups and nations (e.g., current events from newspapers, magazines, television). 4.7 analyze and illustrate the major issues concerning history, culture, tribal sovereignty, and current status of the American Indian tribes and bands in Montana and the United States (e.g., gambling, artifacts, repatriation, natural resources, language, jurisdiction). Skill Sets Reading Students will 1.2 integrate new important print/nonprint information with their existing knowledge to draw conclusions and make application. 2.2 identify, analyze, and evaluate literary elements (e.g., plot, character, theme, setting, point of view, conflict). 4.2 read to evaluate appropriate resource material for a specific task. Literature Students will 1.1 propose and pursue questions and answers to the complex elements of literary works (e.g., historical and cultural influence, style, figures of speech). 1.5 compare and contrast individual and group responses/reactions with author’s purpose/intent. 1.6 demonstrate oral, written, and/or artistic responses to ideas and feelings generated in literary works. 3.2 develop and apply criteria to evaluate the reliability, authenticity, and literary merit of information conveyed in a literary work. 4.1 select, read, listen to, and view a variety of traditional and contemporary works from diverse cultures (e.g., American Indian works), genders, genres, historical periods, and styles. 4.2 demonstrate how factors of history and culture, gender and genre, influence and give meaning to literature. Learning Experiences – Inquiry Unit Essential Questions for this lesson: Can assess the validity of Welch’s account of this massacre? Does assessing historical accuracy add to, detract from, or not affect the power of the account? Placement of lesson: Just after the massacre account, Chapter 35. Before Immersion: Word Splash. Have students share some words that are evoked by the reading or words they saw in the text of Chapter 35. Make a display of the words. You could add a grammar piece by first asking for nouns, then verbs, then adjectives about or from the chapter. Ask students to discuss what part(s) they found most disturbing. Would it be more, less or just as disturbing if this were a true event, portrayed in a historically accurate way? During Option A: to be used with more advanced students or those who might be turning this into a short historical study. 1. Provide students with copies of Chapter 3, “The Massacre on the Marias,” from Walter’s Montana Campfire Tales. This is a detailed account of the events leading up to and including the massacre by a notable Montana historian. 2. Have them read to the top of page 34, which will be a review of information they already know from previous studies in this class. Then have them study the map on page 35. Overlay this map with one that shows contemporary Montana, complete with towns and reservations. Students might have a better sense of location that way. 3. Read on out loud to the middle of page 37. The text says, “Blackfeet chiefs lost control of their young warriors.” Stop and ask students to respond in a double-entry journal to that line. What does it remind them of? How can they connect it to the novel? A double-entry journal will have text quotes in the left column and responses in the right column. 4. Have students complete the chapter, writing in their double-entry journals as they read. This will probably take overnight. 5. The next day, or when they’re done, have students pair up and take turns sharing their quotes and responses. They can pay attention to whether they’ve written any of the same quotes and had the same responses. 6. Then share as a whole group. This can be the lead-in to the After reading section, below. You should attempt to address the historical detail and how Welch took an event that could be related in an unbiased fashion and turned it into part of his novel (the writer’s craft). You can also talk about whether students find reading the historical account helpful or not, and whether it would be useful to read it before reading that part in the novel so they could be better prepared for it. Option B: to be used with less advanced students or in a class that needs to move along quickly. 1. Provide students with copies of Internet articles about the Marias Massacre. Two sites are listed below; much of what you will find on the Internet is copied from site to site. There is also a collection of sites written by the same author or two, but they are first-person accounts re-invented or filtered through these two authors, so you might be cautious about using those. 2. Have students highlight any names or place names that they recognize from the text as they read. 3. Facilitate a group discussion about what they saw. Based on their careful reading, students should also discuss how accurate these descriptions are compared to the novel. Are there any major differences? Do students sense that Welch got the information from these same sources (albeit not on the Internet) or does his information simply arise from the same places as the sources’ information does? After Students should be given the opportunity to discuss their feelings, as this is one of the more horrific events of the book, as well as the climax of its plot. You could begin by charting the plot of the story, leading to this. Students might decide the climax is something else, so be open to discussion. If this is the climax, it is certainly negative; so, what is this story’s expected outcome? Is it a story of hope? Could something hopeful happen at the end of the story to lift it up? Does it have anything to offer, moral-wise? Extension Activities 1. Students could easily turn to a historical research project on the Marias Massacre, USIndian relations 1850-1900, and/or a timeline of events in Blackfeet history. An excerpt on Fools Crow from Dorothea Susag’s book, Roots and Branches, is provided at the website listed below. I have also included the citation for her book, even though it is out of print, in case you can locate it. Investigating federal policies would meet Essential Understanding 6 above. 2. An evaluative essay is also an appropriate extension here: does this horrible event near the end of the book ruin or exalt the novel, in students’ opinions? 3. Students can write a newspaper article from the perspective of either the Blackfeet or the soldiers. They should focus on facts rather than feelings or the human-interest side; depending on their perspective, they might end up with very different stories. You could choose to have half the class write from one perspective and the other half write from the other perspective; then they could see how different “unbiased” articles can turn out. Resources and References “Marias Massacre.” 3 June 2007. Wikipedia. 19 June 2007 <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marias_Massacre>. “The Marias Massacre.” Sept. 2005. Legends of America. 19 June 2007 <http://www.legendsofamerica.com/NA-MariasMassacre.html>. “Resources on Fools Crow.” Montana Center for the Book. 19 June 2007 <http://www.montanabook.org/susag.htm>. Susag, Dorothea. Roots and Branches: A Resource of Native American Literature-Themes, Lessons, and Bibliographies, Urbana, IL: NCTE, 1998. Walter, Dave. Montana Campfire Tales. Guilford, CT: TwoDot Press, 1997.