The Road to Brown v. Board of Education

advertisement

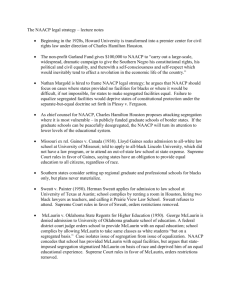

Handout 2.1 The Road to Brown v. Board of Education In 1954 the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that segregated schools were “inherently unequal” and a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution. But while Brown v. Board of Education is a well-known case in American history, people do not always realize that this ruling was part of a campaign that began 25 years before Brown made it to the Supreme Court. In addition, Brown v. Board of Education was heard in conjunction with four other cases in which parents sought equal educational opportunities for their children. All lawyers, parents, and community members who joined this fight against racial injustice did so at their own personal risk and many lost jobs, friends, and even had their homes burned and safety threatened. Legal Campaign Two institutions were vital in the effort to use the courts to challenge legal segregation in the United States. One was Howard University School of Law, the prestigious Black University in Washington, DC. The other was the NAACP, an organization that had been fighting racial injustice since 1909. The NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) was founded in 1909, making it the oldest civil rights organization in the nation. In the 1920s and 1930s the NAACP led awareness campaigns to end lynching and other racial violence, the denial of voting rights, and the segregation of public facilities. One of the NAACP’s major goals since its inception has been a fully integrated society with equal rights for all people. Headquartered in New York City, the NAACP established branch offices in cities throughout the country (with over 300 of them established by 1920). The NAACP employed (and still employs) lawyers, lobbyists, writers, and community organizers to help reach its goals of equality for all people. Charles Hamilton Houston became the vice-dean of Howard University’s Law School in 1929. His goal was to produce excellent lawyers who would use their skill to become Civil Rights advocates. Houston believed that by attacking the laws and legal processes that discriminated against African American citizens, lawyers could fight racism and cause positive social change. One of Houston’s star students was Thurgood Marshall, who would later become the most famous civil rights lawyer in the country and eventually go on to become the first African American justice on the Supreme Court. While Houston was training Marshall, the NAACP was investigating possible legal strategies to end racial segregation. In 1930, the NAACP commissioned attorney Nathan Margold to come up with a plan for challenging segregation laws. His suggestion? Challenge the inherent inequality of segregated primary and secondary schools. In 1934 Charles Houston left Howard to become the head of the NAACP legal team. He invited his former student Thurgood Marshall to join the team as well. At this time, Houston thought that the strategy for ending segregation in schools laid out in the Margold Report was too much to attempt all at once. Instead, the lawyers at the NAACP would try to set legal precedent for desegregation by seeking equal graduate and professional schools for African American students. By 1938, Houston had stepped down as head of the NAACP’s legal department and left Marshall in charge. Houston would continue to practice law and assist the NAACP with cases at times. Between 1938 and 1950 the NAACP won four cases involving equal access to graduate schools. In each case, the NAACP lawyers would seek out a qualified African American student to apply to a graduate program (mostly law schools) at an all White university and then take the school to court when they did not admit them. In Missouri ex. rel. Gaines v. Canada (1938), Lloyd Gaines applied to the University of Missouri Law School. Since there was no law school in the state of Missouri that admitted African American students, the University offered him a scholarship to an out-of-state law school. This case reached the Supreme Court where Charles Houston convinced the justices that the state had to establish an equal facility for African American students or admit Gaines to a state school. In Sipuel v. Oklahoma State Regents (1949), Ada Sipuel applied to the University of Oklahoma Law School and was denied admission. With the NAACP’s help, Sipuel sued the school. The University chose to admit her rather than endure a lengthy court battle. In Sweatt v. Painter (1950) and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents (1950), the Supreme Court ruled that part of the educational experience of graduate school was having the opportunity to interact with other students. Thus, separating students by race did not create equal educational opportunities for the students. With these legal precedents in place, the NAACP felt it had a chance at successfully ending segregation in all schools in the United States. Summarized from the Smithsonian’s Separate is Not Equal website: http://americanhistory.si.edu/brown/index.html Handout 2.2 Case Study Files Clarendon County, South Carolina Summary: In Briggs v. Elliot, 20 African American parents in Clarendon County in rural South Carolina demanded that their children be allowed to attend white schools rather than the starkly inferior schools they were attending. Many of these parents lost their jobs as a result of their stand against segregation. Others were threatened harshly enough that they moved away from the area fearing for their lives. The local NAACP lawyer knew that the national office was looking for school cases challenging segregation and invited Thurgood Marshall to participate in the case when it reached the state level. Marshall and the other lawyers argued that attending segregated schools harmed African American children psychologically and violated the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees equal protection under the law. Of the three-judge panel of the South Carolina federal court, two ruled against the parents, stating that separate but equal facilities were legal and one judge wrote a dissenting opinion stating that South Carolina’s segregated school system was a system of inequality and did not provide African American children equal protection under the law. The NAACP lawyers appealed the case to the Supreme Court. Other Resources: Other accounts of the story: http://www.civilrights.org/education/brown/briggs.html http://www.nps.gov/archive/brvb/pages/briggs.htm http://www.bdpfoundation.org/history.html Photographs relating to the case are on the next page. Handout 2.2a Handout 2.2b Handout 2.3 Case Study Files Claymont and Hockessin, Delaware Summary: In Bulah v. Gebhart and Belton v. Gebhart, mothers Sarah Bulah and Ethel Belton along with seven other parents in the community, complained that the schools their children were allowed to attend were far away from where the homes and neighborhoods where African American children lived. In this case, the Delaware Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s ruling that stated that the African American children were receiving an inferior education in their segregated schools and should be admitted to White schools. They did not, however, strike down the separate but equal doctrine, citing the Supreme Court of the United States as the only institution with the authority to reverse its own ruling. The lawyers representing the schools appealed to the Supreme Court. Other Resources: Other accounts of the story: http://www.civilrights.org/education/brown/belton.html http://brownvboard.org/media/delaware.php http://www.nps.gov/archive/brvb/pages/belton.htm Handout 2.4 Case Study Files Prince Edward County, Virginia Summary: In Davis v. School Board of Prince Edward County, sixteen-year-old high school student Barbara Johns organized a student strike during which students demanded a new school building for African American students that was equal to the one for White students. When NAACP lawyers got involved in the Farmville, Virginia case, they convinced the students to demand integration. The federal court in Richmond, Virginia, upheld Prince Edward County’s right to maintain segregated schools. The NAACP lawyers appealed to the Supreme Court. Online Resources: A more detailed version of the story: http://www.civilrights.org/education/brown/davis.html A more detailed explanation with photographs of the school facilities in Prince Edward County: http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/davis-case/ The decision from the district court: http://brownvboard.org/research/opinions/davis.htm Information about Barbara Johns: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/stories_people_johns.html http://americanhistory.si.edu/brown/history/4-five/detail/barbara-johns.html http://www.biography.com/articles/Barbara-Johns-206527 Handout 2.5 Case Study Files Topeka, Kansas Summary: In Topeka, Kansas in the 1950s, schools were segregated by race. Each day, Linda Brown and her sister, Terry Lynn, had to walk through a dangerous railroad switchyard to get to the bus stop for the ride to their all- black elementary school. There was a school closer to the Brown's house, but it was only for white students. Topeka was not the only town to experience segregation. Segregation in schools and other public places was common throughout the South and elsewhere. This segregation based on race was legal because of a landmark Supreme Court case called Plessy v. Ferguson, which was decided in 1896. In that case, the Court said that as long as segregated facilities were equal in quality segregation did not violate the Constitution. However, the Brown's disagreed. Linda Brown and her family believed that the segregated school system did violate the Constitution. In particular, they believed that the system violated the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteeing that people will be treated equally under the law. No State shall . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. —Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution © 2000 Street Law, Inc. and the Supreme Court Historical Society 7 Visit www.landmarkcases.org Other resources: Summaries of what happened: http://www.nps.gov/brvb/historyculture/kansas.htm http://americanhistory.si.edu/brown/history/4-five/topeka-kansas-1.html Information about Topeka’s race relations in 1954: http://www.tolerance.org/magazine/number-25-spring-2004/brown-v-board-united-states-circa-1954 Handout 2.6 Case Study Files Washington DC Summary: In Bolling v. Sharpe, twelve-year-old- Spottswood Bolling and four other students from Washington, DC, sought admission to the new, well-equipped white schools. The segregated schools for African American students were overcrowded and badly equipped. The US District Court dismissed the case saying that separate but equal was still the law of the land. The Supreme Court asked to review the case in conjunction with Brown v. Board of Education and the other school segregation cases that were already under review. Other Resources: Other accounts of the story: http://www.nps.gov/archive/brvb/pages/bolling.htm http://americanhistory.si.edu/brown/history/4-five/washington-dc-1.html Note Taking Chart Handout 2.7 Case Location Brown v. Board of Education Topeka, Kansas Bolling v. Sharpe Washington, DC Bulah v. Gebhart and Belton v. Gebhart Delaware Davis v. School Board of Prince Prince Edward County Edward County, Virginia Briggs v. Elliott Clarendon County, South Carolina Complaint Issues Ruling Handout 2.8 Key Excerpts from the Majority Opinion, Brown I The decision was unanimous. Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the opinion of the Court. . . . Here . . . there are findings below that the Negro and white schools involved have been equalized, or are being equalized, with respect to buildings, curricula, qualifications, and salaries of teachers, and other "tangible" factors. Our decision, therefore, cannot turn on merely a comparison of these tangible factors in the Negro and white schools involved in each of these cases. We must look instead to the effect of segregation itself on public education. . . . Today, education is perhaps the most important function of state and local governments. Compulsory school attendance laws and the great expenditures for education both demonstrate our recognition of the importance of education to our democratic society. . . . Today it is a principal instrument in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him for later professional training, and in helping him to adjust normally to his environment. In these days, it is doubtful that any child may reasonably be expected to succeed in life if he is denied the opportunity of an education. Such an opportunity, where the state has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made available to all on equal terms. . . . To separate them [children in grade and high schools] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely to ever be undone. . . . Whatever may have been the extent of psychological knowledge at the time of Plessy v. Ferguson, this finding is amply supported by modern authority. . . . We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and other similarly situated . . . are . . . deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. After the decision in Brown was reached, the Court decided a companion case Bolling v. Sharpe regarding the same issue of segregation in the District of Columbia. The Court notes first that although the Fourteenth Amendment is only applicable to states, the Fifth Amendment is applicable to the District of Columbia. The Court then held that while the Fifth Amendment does not contain an equal protection clause it does contain a due process clause, the concepts both stemming from the American ideal of fairness, and discrimination can be so unjustifiable it can be deemed violative of due process. © 2000 Street Law, Inc. and the Supreme Court Historical Society Visit www.landmarkcases.org Handout 2.9 Key Excerpts from the Majority Opinion, Brown II The decision was unanimous. Chief Justice Earl Warren delivered the opinion of the Court. These cases [Brown and others] were decided on May 17, 1954. The opinions of that date, declaring the fundamental principle that racial discrimination in public education is unconstitutional, are incorporated herein by reference. All provisions of federal state, or local law requiring or permitting such discrimination must yield to this principle. There remains for consideration the manner in which relief is to be accorded. . .. Full implementation of these constitutional principles may require solution of varied local school problems. School authorities have the primary responsibility for elucidating, assessing, and solving these problems; courts will have to consider whether the action of school authorities constitutes good faith implementation of the governing constitutional principles. . . . While giving weight to . . . public and private considerations, the courts will require that the defendants make a prompt and reasonable start toward full compliance with our May 17, 1954, ruling. Once such a start has been made, the courts may find that additional time is necessary to carry out the ruling in an effective manner. The burden rests upon the defendants to establish that such time is necessary in the public interest and is consistent with good faith compliance at the earliest practicable date. To that end, the courts may consider problems related to administration, arising from the physical condition of the school plant, the school transportation system, personnel, revision of school districts and attendance areas into compact units to achieve a system of determining admission to the public schools on a nonracial basis, and revision of local laws and regulations which may be necessary in solving the foregoing problems. . . . [T]he cases are remanded to the District Courts to take such proceedings and enter such orders and decrees consistent with this opinion as are necessary and proper to admit to public schools on a racially nondiscriminatory basis with all deliberate speed the parties to these cases. © 2000 Street Law, Inc. and the Supreme Court Historical Society Visit www.landmarkcases.org