Black, a Base Blot on the Canvas of Elizabethan England: Racism in

advertisement

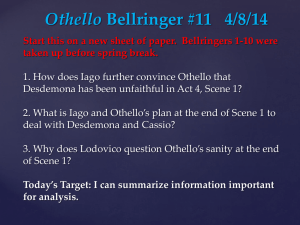

Black, a Base Blot on the Canvas of Elizabethan England: Racism in Shakespeare's Othello? Instructor: Professor Wang Name: 魏逸昀 49782031, 蔡淙名 49782047, 侯柔瑋 40782033, 李辰薇 49782037, 戴禮淳 49782013, 趙敏 49782010 Date: 2010/1/11 Racial discrimination has existed for centuries. It is always a controversial issue to discuss with. Obviously, it appears frequently in Othello. Then, what if we discuss the play with racism? Does racism equal racial discrimination? Moreover, if we take racism as our main perspective, we wonder that who should be responsible for the tragedy. Should Othello be responsible because of his inferiority complex about his own race, Moor? Or should Iago take the responsibility because he plans everything? No matter who it is, certainly, racism plays an important role in the text. But before we look into the text and the racism in it, we must deal with the term “racism” at first. After all, what is racism and does it really exist in Othello? According to the definition of Merriam-Webster's Dictionary, racism is “a belief that race is the primary determinant of human traits and capacities and that racial differences produce an inherent superiority or inferiority of a particular racial group, and that it is also the prejudice based on such a belief.” It seems applicable to this play. However, it is inappropriate to claim that Shakespeare does bear this concept in mind, for it is a modern concept and did not emerge before the 20th century. Also, rather than applying the definition from modern times, we prefer turning to the text, digging into it, and unearthing something that reminds us racial discrimination. Because we believe that, disguised in so-called modern concept mentioned above, there should be something else, though still similar to that concept actually, existing in Shakespeare’s Othello. Therefore, we’d like to introduce Kay Adenstedt’s (2009) viewpoint and adopt his formulation as our main perspective when we discuss Shakespeare’s Othello. As Hall has pointed out quite clearly, a modern reader is very tempted to associate any offending statement against a coloured person with conceptions of racism. However, it is crucial to question oneself for a moment whether or not this notion is applicable at all to Shakespeare′s play. The task 1 above suggests that Shakespeare represented racialism in Othello. … … Nevertheless, if one takes a general definition of racism and takes it part, it is possible to imagine that a notion of "unfair treatment [prejudice, violence, discrimination] of people who belong to a different race; the belief that some people are better than others" could have been shared by Elizabethans on a personal level as well. So, we assume it the “conceptual racism”, the kind which is composed of prejudice, violence, unfair treatment and discrimination to the people belonging to different races, and the kind which is a notion exists in Shakespeare’s mind and in the characters’ he made as well. Nevertheless, where this notion comes from? And in what way it affects Shakespeare when he invents Othello, a Moor? In reading Othello, we can see a vivid cultural stereotype set upon the “Moor.” Shakespeare’s usage of the protagonist as a foreigner who has different racial identity with other people in the same age is really a bold act and makes readers think that Shakespeare agrees the same cultural stereotype of the Moor with them. However, in Othello, Shakespeare repeatedly shows the positive images of his protagonist who is a brave general and an honest husband and who loves his wife sincerely and deeply. Hence, some scholars attested that Shakespeare actually tried to break this stereotype and approved of the value of the Moor. What on earth the term “Moor” stands for to the real society Shakespeare lived in, even to Shakespeare himself? The term “Moor” is problematic because of its changeable significance. Early, there was no negative meaning in the term “Moor,” but just signified “Berber,” a particular Muslim people in North Africa. In Conquerors and Chronicles of Early Medieval Spain, as a Christian who had lived in al-Andalus under Muslim rule, Wolf talks about the invasion of Muslims without any racial hostility (Wolf 1990: 131). Later on, in documents which are authored in the Christian kingdoms of Iberia, the term “Moor” is transformed into a general term for Muslims who are occupying and 2 living in Iberian territory lands. Based on the Encyclopedia Britannica, Moor is loosely applied to any native of Morocco, but in a more serious sense, it only applied to people of Berber, Arab and Spanish descent from North Africa. Modern scholars surprisingly found that there is no ethnological value in the term “Moor” actually. So far, it is obviously that we cannot see any existence of stereotype in the term “Moor.” However, in English drama of the 16th and 17th centuries, Moor was symbolized something rather than human and even something evil. The negative images such as Barbarian, devil, or infidel are often used to describe the Moor. Following is an informative paragraph in The Moor in English Renaissance Drama: Relations between England and Morocco were extremely complex, and the opinions generated by those relations were as varied. What we find is not one image of the Moroccan, but many images, from the dangerously inscrutable alien to the exotically attractive ally. The positive and negative characterizations that emerge from the first fifty years of trade and diplomacy can with ease be related to the specific historical perspectives of trade, war, and diplomacy. But traditional images of the Moor as black devil, Islamic infidel, or oriental despot were certainly drawn on to articulate what traders and diplomats experienced. Optimistic prospects, disappointments and frustrations, and strong prejudices against Catholic Spain were by turn equally strong. Dramatic contexts, too, reflect a give-and-take of opinion, a frequent counterbalancing of prejudices, and interplay of abstract stereotypes and the more complex shadings of experience. (D’Amico, 1991: 39) We can see there are frequent contacts in trade and diplomacy between England and Morocco in this time. The more contacts they have. The more varied opinions of the Moors are generated. D’Amico refers to that the portraits of the Moor are unilaterally controlled by traders and diplomats because of their experience and imagination. However, these portraits are sometimes prejudices and stereotypes, not only due to their different religion and race, but also their preconception of the Moors. 3 Since we realize the realistic racial identity of Moor in Shakespearean times, it will be easier for us to take a closer look at the text and the fictional racial identity made in Othello. We believed that the above-mentioned conceptual notion of racism, which we focus on racial identity in previous paragraphs, has much to do with the murderer of this tragedy. Now we will turn to the text and discuss some plots which are in connection with this kind of notion, by showing characters’ reacts to the Othello’s racial identity, Moor. Furthermore, we will examine that is the term “Moor” presenting the racial discrimination directly and only? That is, is this term always consistent in Othello? In this play, the character who hatches the whole plan is Iago. Because of not being chosen as the lieutenant of Othello, Iago feel envious of Cassio, who gets this position, and felt hatred toward Othello. Hence, he tries to be revenged on Othello. Iago stresses the different racial identity between Othello and others not only to make others prejudice against Othello but also makes Othello himself feel inferior and jealous. For example, Iago said to Brabantio, “…you'll have your daughter covered with a Barbary horse; you'll have your nephews neigh to you; you'll have coursers for cousins and gennets for germans.” (Act I, Scene I, 119-122) Another role who discriminate Othello is Roderigo. He is the partner of Iago’s evil plan. He would help Iago because he wants to marry Desdemona and fails. Therefore, he shows his discrimination when Iago attacks Othello, “What a full fortune does the thicklips owe If he can carry't thus! “ (Act I, Scene I, 67-68) As to the father of Desdemona, Brabantio, he loves Othello because of his braveness 4 and brilliant military exploits, but hates Othello because of his color of skin and difference of race. In this play, Brabantio does not show his discrimination on Othello until knowing that Othello marries his daughter. He says to Othello, “So opposite to marriage that she shunned The wealthy curled darlings of our nation, Would ever have, to incur a general mock, Run from her guardage to the sooty bosom…” (Act I, Scene II, 83) It goes without saying that the discrimination in this play derives from Othello’s racial identity, Moor. However, we find that the term Moor is an interesting word actually. We are wondering that does the term Moor stay consistency in this play. In Othello, we believe “Moor” is the most important term, and most of characters call Othello by using this term. Moreover, some of them use it with no prejudice, but some of them do. For example, Roderigo says, “As partly I find it is, that your fair daughter, At this odd-even and dull watch o' the night, Transported, with no worse nor better guard But with a knave of common hire, a gondolier, To the gross clasps of a lascivious Moor…” (Act I, Scene I, 131-135) What he says is in order to arouse Brabantio’s hatred toward Othello. So here, we can see the term, Moor, with obvious discrimination. In addition, Iago and Brabantio use this term with prejudice most of time whenever they mention Othello. On the other hand, there are some other roles who also mention the term, Moor, but not to look down upon Othello. The most obvious one is Othello’s wife, Desdemona. She loves her husband even though he kills her; hence we know that she would say “Moor” without prejudice. For example, Desdemona says to her father, “…but here's my husband, And so much duty as my mother show'd To you, preferring you before her father, 5 So much I challenge that I may profess Due to the Moor my lord.” (Act I, Scene III, 202-206) As to other roles, for instance, Duke of Venice, Montano, Lodovico, other Senators etc. are also do not show the racial discrimination on Othello while calling him the Moor. They know Othello is a brave general with solid virtue, so they would not use Moor to discriminate him. Therefore, the meaning of the term, Moor, is not identical. In the play, one group of character use “Moor” just to call Othello with no prejudice while some other roles use this “Moor” not only to mention Othello but also show their discrimination. Iago is the most typical character of the latter group. He manipulates Othello’s racial identity, Moor, to carry out his vicious plot, which results in Othello’s inner changes and foreshadows the tragedy. Now, we will see how the mental changes happen and leads to the outset of the tragedy. Turkey was going to attack Venice, and Senators held a meeting and decided to assign Othello to fight against Turkish. Duke thought that Othello could handle the fighting very well. Although Iago hated him, he said that no one could do better than Othello. Because of these facts, Othello is calm and confident when facing those gossip and defamation about his skin color as we discussed above. When Desdemona’s father accused Othello of stealing her daughter who was ‘abused, corrupted by spells and medicines bought of mountebanks’ (Act1, Scene III), Othello’s utterance showed his confident and fearless (Act 1, Scene III). He said that his parts, his title and his perfect soul could manifest him rightly (Act1, Scene II). Then, Iago told to Othello that Cassio and Desdemona had an affair. At first, Othello did not believe. He trusted in Cassio and Desdemona. Othello said that he believed Cassio was an honest man. He also said that although he had weakness, Desdemona would never betray to him. Othello would not doubt her unless he 6 witnessed, and unwilling to believe until there was a proof (Act3, Scene III). Iago kept trying to arouse Othello’s suspicion. He said that when Desdemona married Othello, she deceived her father; similarly, she could also deceive Othello. (Act3, Scene III ) Othello began to shatter his own faith in Desdemona. Othello said that how nature erring from itself (Act3, Scene III). He started to query himself about his skin color and his age, “… To prey at fortune. Haply, for I am black, | And have not those soft parts of conversation | That chamberers have, or, for I am declin’d | Into the vale of years—yet that’s not much— …” (ActⅢ SceneⅢ). He also thought that he was abused by Desdemona and must loathe her. However, he still did believe Desdemona was chaste. But things changed after Othello found the handkerchief which he gave Desdemona as a present missing. His mind was out of control and lost his rationality because now he believed in what he saw. Handkerchief was a symbol of Othello’s love and Desdemona’s faith and chastity. Besides, Othello professed that handkerchief had a magic power that when she kept it, it could acquire and subdue his heart. If she lost it or gave to someone else, their relationship would be the perdition and nothing else could match. Another event that totally evoked Othello’s anger was that he would be sent back to Venice, and that Cassio would take place of his position. Resulted from this anger, he hit Desdemona, which surprised Lodovico, who once praised him as ‘a noble Moor whom our full senate call all in all sufficient, the nature whom passion could not shake and the solid virtue that shot of accident, nor dart of chance, could neither graze nor pierce’ (Act4, Scene I). The handkerchief’s missing and Iago’s instigation made Othello furious to the degree that even Iago had never expected, and that even his beloved Desdemona could be the victim of his anger. Now, Othello was a man who lost all his rationality, though Emilia and Desdemona herself said that she was innocent. He was still impervious to discouragement and killed Desdemona. At 7 the end of Othello, all deceits were clear. Othello confessed that he would out of control and lost rationality after being agitated. Then, he stabbed himself (Act5, Scene II). After understanding Othello’s mental changes and so many supporting evidences in more previous paragraphs, now we are confident enough to go into the core argument we made at beginning. In the play, Othello’s jealousy, which was aroused by Iago, leads to the murder of Desdemona. Then who is the one should be responsible to the tragedy, Othello or Iago? Iago takes revenge because of his anger against Othello and his envy towards Cassio. Iago’s envy, which makes him want to destroy Cassio comes from the fact that what he wanted was given to someone he considered not better than him. As for Othello, his jealousy has much to do with his racial difference from Desdemona. The following is the citation from the book Shakespeare, Race, and Colonialism by Ania Loomba. Othello is partly set in Italy, a setting that in Shakespeare’s plays both reflects, and offers a contrast to, the audience’s England. Italians placed against the Moors, they are part of Christian Europe. Othello, ‘the Moor of Venice’ is a Moor who cannot fully become a part of Venice. His jealousy is rooted in this fact and in his difference from Desdemona, a difference that Iago plays upon in order to persuade Othello that his wife cannot really love him for very long. In Giraldi Cinthio’s Gli Hecatommithi, from which Shakespeare took the story of the unhappy marriage of a Moor and a Venetian lady, Disdemona tells her husband, ‘you Moors are so hot by nature that any little thing moves you to anger and revenge’. Shakespeare has his Desdemona counter this stereotype; when Emilia asks her, ‘Is he not jealous?’ she replies ‘Who, he? I think the sun where he was born | Drew all such humours from him’ (3.4.28-30). But the play goes on to show us that, despite his seeming different from other Moors, Othello ultimately embodies the stereotype of Moorish 8 lust and violence—a jealous, murderous husband of a Christian lady. In this paragraph, Loomba mentions the fundamental of Othello’s jealousy—his Moorish identity in Venice, as well as the disparity between him and Desdemona. Othello’s skin color makes him an outsider of the Venice society, which he lives in. Although in his marriage this was not a problem at the beginning, the discord of racial identity between he and his wife was brought to Othello’s attention by Iago. Being influenced by Iago, Othello starts losing his confidence in himself. Moreover, Iago emphasizes the infidelity of women to reinforce his scheme. He tells Othello that women are not reliable and that Desdemona, who once lied to her father, would be extremely likely to cheat on him. As Loomba said in the book, “… that this match is unusual, ‘unnatural’, and therefore especially fragile…” Othello and Desdemona’s relationship is not blessed by people around them. Most people carry an attitude of racial discrimination toward this marriage. The self-abased feeling about his racial identity and the mistrust on women cause Othello’s jealousy and thus arouses the murder of Desdemona. Iago’s envy makes him a revengeful man, while Othello’s jealousy changes him an irrational husband from a passionate lover. He killed not only his beloved and innocent wife, but also himself. In the above citation, Loomba also mentions a stereotype of Moorish lust and violence. Such characteristics of Othello were not showed initially in the drama; however, they gradually came to the surface along with Othello’s rising jealousy. This sexual jealousy and violent tendency of Moor eventually performed on the murder of Desdemona. Again, the following citation is from the same book by Loomba. …While Othello is the defender of the Christian state against the Muslim threat, he also embodies this threat. At the end of the play, he describes his suicide as an act where his Christian half kills the Muslim half, much as long ago in Aleppo, he had killed ‘a malignant and turbaned Turk’, a 9 ‘circumcised dog’ who had beaten ‘a Venetian and traduced the state’ (5.2.361-3). Despite being a Christian soldier, Othello cannot shed either his blackness or his ‘Turkish’ attributes, and it is his sexual and emotional self, expressed through his relationship with Desdemona, which interrupts and finally disrupts his newly acquired Christian and Venetian identity. In the eyes of many Venetians, he remains illegitimate as Desdemona’s suitor; as her husband, he seems fated to play out the script of jealousy and wife-murder. In this paragraph Loomba talks about Othello’s struggle between his Moorish and Venetian identity. Though living in Venice as the role of Venice protector against Turkish threat, Othello himself was ultimately took over by his Moorish half, his nature. Despite of Iago’s plot and slanderous words, Othello possesses a nature of lust and violence. Such nature drives him to take boisterous response to Iago’s slander. As long as the irrational jealousy and violence defeat his reason, the tragic murder occurs. By taking reference materials and discussing together, we had the common consensus that Othello is the one who should take the responsibility of the tragedy. Because it is Othello, who had possession of the nature of violence, lust and envy. Also, it is Othello who took Iago’s slanders of Desdemona as truth without any verification and evidence. As the result, Othello is the person whom we consider to be responsible for the tragedy murder. 10 Reference Ania Loomba, 2002, Shakespeare, Race, and Colonialism, New York: Oxford University Press Emily C. Bartels, 2008, Speaking of the Moor: From Alcazar to Othello, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Hugh Chisholm, 1911, The Encyclopedia Britannica, New York: The Encyclopædia Britannica Co Jack D’Amico, 1991, The Moor in English Renaissance Drama, Florida: University of South Florida Press. Kenneth Baxter Wolf, 1990, Conquerors and Chronicles of Early Medieval Spain, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. Ross Brann, The Moors?, Published doctoral dissertation, University of Cornell, Department of Near Eastern Studies, New York 蔡茂堂, 2007, 愛與嫉妒 ,Retrieved January 9, 2009, from website: http://blog.xuite.net/daphne/blog/9632396 11