The 1950s

advertisement

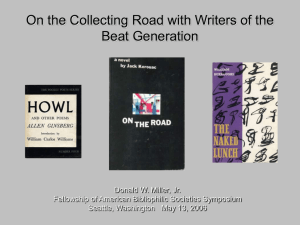

The 1950s As much as Fahrenheit 451 is about a time in the not-too-distant future, Ray Bradbury’s novel is anchored in the 1950s. Mildred Montag sits like a zombie in front of a telescreen. The sound of jet fighters crosses the sky in preparation for war. A neighborhood sits full of cookie-cutter houses and the complacent souls who live in them. All of these would have been familiar scenes to a writer at work in 1953. The era following World War II in the United States was known for its productivity, its affluence, and its social conformity. The economy was strong. The technology of television, air travel, and the transistor brought the future to the front stoop. The neighborhood Montag lives in probably looks a lot like Levittown, the famous low-cost housing developments of the age that ushered in the rise of suburbia. Although the 1950s are remembered as a decade of peace and prosperity, they were anything but. The Korean War, which ended in the year that Fahrenheit 451 was published, saw tens of thousands of American deaths. The larger Cold War that lingered was a source of constant anxiety. In the new atomic age, everyone was learning that the world could be destroyed with the push of a button, a fate Bradbury more than hints at in his novel. Not only were governments endowed with nuclear weapons, they exercised the power to persecute suspected enemies closer to home. The congressional House Committee on UnAmerican Activities began investigating suspected espionage in 1946, and within a few years Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin was charging, without evidence, that dozens of government officials were Communist Party members. Meanwhile, memories of Nazi book burnings and Soviet censorship were still fresh in people’s minds. As a result, censorship was alive and well in the media. Communists were assailed in the press. Comic books were condemned as subversive by parents and educators. Images of the “organization man” and the “lonely crowd” reflected changes in the American spirit. For all their prosperity and rising expectations, the 1950s were a decade of atomic tests and regional wars; racial segregation; government censorship and persecution; subtly enforced social orthodoxy; and building angst. The social and psychological problems of the era are watchfully scrutinized in Fahrenheit 451, a book that examines an intolerant society that seems oddly un-American in its penchant for censorship and governmental control. (The big read: http://www.neabigread.org/) The Beats and the 1950s The 1950's represented, what W. H. Auden called, an "Age of Anxiety," between the victory of World War II and the specter of nuclear annihilation. The 1950s was also a time when many of the nation's younger generation began to challenge Conformity. The Beat Culture began at this time and continued with other countercultures and finally to the hippies of the 1960s. According to John Clellon Holmes, Jack Kerouac's On the Road, the most important book of the Beat Generation, "described the experiences and attitudes of a restless group of young Americans, whose primary interests seemed to be fast cars, wild parties, modern jazz...and other miscellaneous kicks: Somewhere along the line I knew there'd be girls, visions, everything; somewhere along the line the pearl would be handed to me (Jack Kerouac, On the Road, Part 1, Ch. 1). What differentiated the characters in On The Road from the slum bred petty criminals was Kerouac's insistence that actually they were on a quest, and that the specific object of their quest was spiritual. Kerouac wanted visions: The only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn, like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes "Awww!" ~ Jack Kerouac The Beats weren’t looking for spirituality in church or school; following Emerson’s advice, the Beats looked for spirituality in Nature and themselves. Perhaps the quest of the Beats might be placed into a context of the vision of Ralph Waldo Emerson, when he gave an address to the Harvard Phi Beta Kappa society in which he claimed that character is higher than intellect, and experience counts more than book learning. Emerson told that august crowd to get out of school and experience life for themselves. Thoreau got it. And so did the Beats. On the road, Kerouac and friends looked for a new American Identity, separate from those dead ideas inherited from Europe. Out in the vast landscape of the American continent, an individual, committed to self-reliance, novelty, and change, could make contact with the ultimate inspiration: So in America when the sun goes down and I sit on the old broken-down river pier watching the long, long skies over New Jersey and sense all that raw land that rolls in one unbelievable huge bulge over to the West Coast, and all that road going, and all the people dreaming in the immensity of it... and tonight the stars'll be out (Jack Kerouac, On the Road, Part 5) Historian Imre Saluszinsky has explored the connection between Emerson's call for a new American Identity and the Beat Generation and today's culture. For example, Emerson taught that spirituality can best be found in Nature: In fact the Beat idea of the American continent as the ultimate source of all inspiration comes from Emerson, who singlehandedly convinced the young American poets and thinkers of the 19th century that they could forget Europe and history, and forge an original relation to nature. And the radical individualism of the Existentialists, with its sense of all worldly power as corrupt and corrupting: that is also there in Emerson, who writes, "Society everywhere is in conspiracy against the manhood of everyone of its members." Contemporary cultural icon, Bob Dylan, has been perfectly open about his early influences: "I came out of the wilderness, and just naturally fell in with the Beat scene . . . it was Jack Kerouac, Ginsberg, Corso and Ferlinghetti . . . I got in at the tail end of that and it was magic." Saluszinsky suggests that today's counter-culture goes back to "Emerson's chief lesson --that memory and history are death to the creative spirit, which must be committed to novelty and change --- is evident everywhere in Dylan who saw immediately that one way of changing the times is simply to assert that they already are a-changin'...This spirit of Emerson and Hawthorne --- who looked West from New England and there, in the opposite direction to Europe, found a symbol of action and renewal ...Self-reliance is not in every respect a comforting or easy truth to live by: it teaches that we must compete and struggle endlessly, if we are to escape the limiting influence of others." As Dylan suggests: Leave your stepping stones behind, something calls for you, Forget the dead you've left, they will not follow you . . . Strike another match, go start anew And it's all over now, Baby Blue. (http://www.umsl.edu/~ryanga/amer.studies/amst.thebeats.html, compiled from Auden and W. H. Auden and John Clellon Holmes stuff comes from the textbook: The American Tradition in Literature, 11th Edition, Perkins and Perkins, McGraw Hill.and The Americans, authors Danzer, Klor de Alva, Krieger, Wilson, Woloch, Online edition, 2003 (All page references here refer to the print edition 2003). )