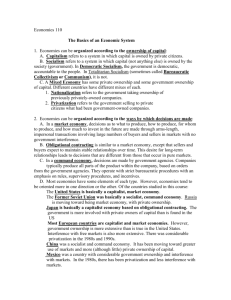

Chapter 4 The Social Market Economy

advertisement