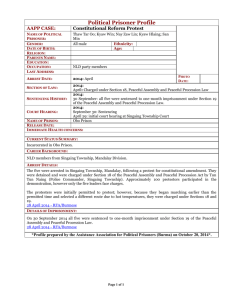

Freedom of Expression and Peaceful Assembly in Georgia

advertisement