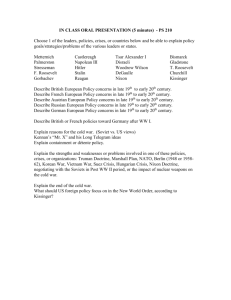

DelPeroPresentation.doc

advertisement