Faust.doc

advertisement

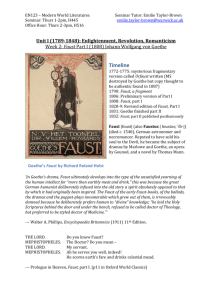

FAUST ROMANTICISM Intensity Innovation Irreverence Insubordination Individualism Imagination P. 133 MYTHIC STATURE As with the story of Don Juan, there have again been many musical versions, including operas by Berlioz, Boito, Gounod, and Pousseur and other works by Liszt, Wagner, Schumann, and Rachmaninoff. There have also been many important literary versions, ranging from Christopher Marlowe’s Elizabethan play, two hundred years before Goethe’s Faust, to more recent works by, to take only the greatest masters, the Russians Alexander Pushkin and Ivan Turgenev, the Portuguese Fernando Pessoa, the Frenchmen Paul Valéry and Michel Butor, the German Thomas Mann, and the American Gertrude Stein. The Don Juan and Faust stories are among the modern Western world’s few great myths, along with those of, say, Don Quixote, Robinson Crusoe, and Great Expectations. On the one hand, the themes these stories treat are central to the modern Western experience. On the other, the stories are open enough, flexible enough, to accommodate the concerns of very different kinds of writers and audiences in different times and places, and most of them have been treated again and again by subsequent playwrights and novelists. To take just a few prominent recent examples, there have been important retellings of Don Quixote, Robinson Crusoe, and Great Expectations by major French, South African, Argentine, Australian, and American writers. These myths “basic plots, their enduring images, all exhibit a single-minded pursuit by the protagonist of one of the characteristic aspirations of Western man. Each of their heroes embodies an arete and a hubris, an exceptional prowess and a vitiating excess, in spheres of action that are particularly important in our culture. Don Quixote, the impetuous generosity and the limiting blindness of chivalric idealism; Don Juan, pursuing and at the same time tormented by the idea of boundless experience of women; Faustus, the great knower, whose curiosity, always unsatisfied, brings damnation.” CONTRARIES Another principle of Romanticism, not as central or widespread as the five I’s, is best expressed in a famous passage from William Blake, the English Romantic poet-painter, who wrote: “Without contraries is no progression. Attraction and repulsion, reason and energy, love and hate, are necessary to human existence.” We saw something like this in the deliberate tensions of Don Giovanni. In Faust, we see it more explicitly, in passages such as these: P. 171, ll. 1765-67 P. 186, ll. 2921-23 Contraries are like opposites, but they are characterized by the possibility of a transcending third term. In this, they are like the dialectics of Blake’s contemporary, the German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, whose method involved starting with a thesis and its antithesis, and then finding the resulting synthesis. We can see all this in the “Prelude on the Stage,” which presents a number of the play’s underlying themes in terms of contraries. The Director and the Poet take antithetical positions, while the Clown finds syntheses. [USE CHART] The “Prelude on the Stage” also seems surprisingly modern. Most playwrights ask us to suspend our disbelief and accept, as long as the curtains are open, that what happens on stage is reality. The “Prelude,” on the other hand, deliberately reminds us that what follows is a play. It does so, moreover, by placing on the stage two actors playing the fictional roles of the Poet and the Director. Thus, the “Prelude” is already distanced from reality at one level, and the ensuing play is distanced at two levels. Indeed, since the middleaged scholar Faust uses a disguise—that of a youthful aristocrat—provided by the witch’s potion to play his role as Gretchen’s lover, there is a sense in which the Gretchen story is yet another play within the play, at a third distance from reality. There have always been occasional exceptions, but one doesn’t see a lot of this sort of literary play until twentieth-century Modernism. PROLOGUE IN HEAVEN ”Neither the ‘Dedication’ nor the ‘Prelude on the Stage’ contains anything that is related to the action of the play: the first states the poet’s attitude toward the material he is about to present, the second indicates the special nature of the spectacle to be produced. But the bearing of the ‘Prologue in Heaven’ upon the subsequent plot cannot be overemphasized—it is the key to everything that is to come. Challenged by Mephistopheles, the Lord insists that the sense of discrimination between good and evil, even though it may not easily be realized in a life of positive action, represents the true character of the human being. As long as this perception of values is active, it should entitle man to eventual salvation. This is the meaning of the term ‘striving’ which the Lord recognizes as the essence of man’s character and which, not in the sense of aggressive and amoral ruthlessness, but of a persistent power of moral judgment, Goethe offers as the central concept of Faust’s career.” This scene has a very clear literary precedent with which many of you are familiar. What is it? Job Goethe certainly expected his readers to make this connection. What are its implications for our understanding of Faust’s story? In earlier versions of Faust’s story, the use of black magic and/or the question of damnation had often been the central concern. Here it becomes “the nature or condition of man himself.” (H) This, as much as anything else, makes Goethe’s version the most universal, as well as the most relevant for the essentially secular modern world. FELIX CULPA Define As in “felicitous” and “Feliz Navidad” As in “culprit” The contemporaries of the real, 16thcentury Faust saw his story “as an object lesson and a warning. To the age of Goethe, on the other hand, it was natural to look upon Faust as a prototype of man’s ideal aspirations. Faust appealed to Goethe as a symbol of man’s emancipation from authority. Regardless of whether Faust’s path would eventually lead him to perdition or to salvation, his courage in daring to trespass upon the realm of the forbidden makes him a heroic figure. A century earlier the English poet John Milton still founded his epic Paradise Lost on the theme of ‘man’s first disobedience.’ This involved the axiomatic acknowledgment of divine arbitrary authority: we must unquestioningly follow God’s law. The eighteenth century, on the other hand, was set to challenge all arbitrary authority. Goethe’s friend, the playwright Friedrich Schiller, while conceding that the Biblical Fall precipitated a catastrophe, takes pains to point out that the Fall was also an absolutely necessary first step in the higher development of mankind. With the Fall, the mind of man embarks on the realization of its limitless potentialities. Without it, he would forever have remained a child of Nature, innocent but ignorant, unable to develop the faculties of distinguishing between good and evil.”—Weigand PLOT “When we first meet Faust he is a man of incomparable learning who has mastered every field of knowledge without, however, having found anywhere the reassurance of insight into ultimate meanings. As he speculates upon the symbols of cosmic significance, he must admit his human limitations; he can only hope, through the Earth Spirit, to reach an understanding at least of all earthly experience. But that, too, is shown to be impossible. His despair is profound.”— Victor Lange The bargain is struck, and Faust easily resists the repellent temptations of the drinking students and the witch’s kitchen, but he succumbs to that of Gretchen, with dire consequences. “In the satanic frenzy of the Walpurgisnight, Faust seems for a brief moment close to a total suspension of moral perception. But the most powerful means of seduction cannot destroy Faust’s memory of Gretchen; as he comes to rescue her, he is overwhelmed by the spectacle of a moral decision in Gretchen that is clearer and, in spite of her madness, more resolute than he himself can achieve. She refuses to be freed by Mephistophelian devices and submits to the judgment of God. Faust, most deeply stirred and here, perhaps, farthest from the kind of amorality that Mephistopheles hopes to achieve, is forcibly reminded of his attachment to his servant; as a voice from above promises Gretchen forgiveness, Mephistopheles disappears with Faust.”—Lange “Gretchen’s initial response to Faust’s intention to save her is wanting him to embrace her. But this would represent the loss of the bet for Faust because it means returning to the past, asking for time to stand still, rather than wanting more. Pure Gretchen is thus the strongest temptation Mephistopheles can offer to win Faust’s soul. And paradoxically, to win his bet with Mephistopheles and to be saved in the terms of the Lord in the ‘Prologue in Heaven,’ Faust must leave Gretchen to her fate, not rescue her like a bold hero. Only when he refuses to kiss her does she nobly decide to stay within the limitations of her social world and to take the consequences of her action.”—Damrosch CYCLICALITY A central theme of Faust, although not an obvious one, is time, and a particular kind of time. There are essentially two ways of viewing time, and thus viewing life and history: moving in cycles or moving toward a close. Goethe foregrounds the cyclical view almost immediately in Faust, by making it the subject of the hymn of the three angels on pp. 140-141. ll. 243-46: the sun ll. 251-54: earth ll. 255-58: tides ll. 259-60: weather Form echoes substance: the regular rhythms embody the cyclical subject. “In fewer than a hundred lines after Wagner leaves, Faust works himself into a suicidal despair. This is partly because Faust is merely human and incapable of confronting the Earth Spirit as an equal, but more because as human he is subject to time and the conditions of mortal life.”—H This monologue exemplifies “what has come to be called Romantic despair.”—H We see it, for example, in English-language works such as Wordsworth’s great poem “Resolution and Independence,” in which the poet takes a walk and observes the joyfulness of the natural world: I heard the sky-lark warbling in the sky; And I bethought me of the playful hare: Even such a happy Child of earth am I; Even as these blissful creatures do I fare; Far from the world I walk, and from all care; But there may come another day to me— Solitude, pain of heart, distress, and poverty. What pulls Faust out of it? Easter music, evoking the festival of resurrection, rebirth Faust is not a Christian believer, but he is stirred by the concept of rebirth and cyclicality in both the life of Christ and the return of Spring. “Easter is a new Christian form of an ancient Spring celebration.” The setting and the structure of the scene also demonstrate the effects of renewal as an emergence, an opening outward. The citizens of the town proceed out of the narrow city gate and into the countryside as if they were being released from the imprisonment of winter and society. Initially, the perspective of the scene is fixed at a convenient vantage point near the gate; later on, after Faust’s opening speech, the setting moves with Faust and Wagner almost cinematically as they make their way, first, to the village with its rustic festival, then to the top of a hill, where they watch the sun go down, and finally back to the city gate, returning at evening to protection and enclosure. The scene thus assumes a cyclical structure, moving with Faust as he makes his journey from morning to evening out from the city to the limits of human habitation and then back again.”—H “Faust responds to the Easter music as to a heavenly visitation. Though he denies faith, he nonetheless acknowledges the validity of the Easter ritual as a miracle of rebirth for the faithful. In contrast to the appearance of the Earth Spirit, who was conjured by Faust through a magical sign, the Easter Chorus comes over him unexpectedly and by surprise, a gift of grace at the moment when he is about to drink the poison. The balance and contrast of these two spiritual visitations is central to Faust’s exsperience both in this opening scene and in the drama as a whole. The Easter resurrection clearly prefigures Faust’s ultimate salvation.”—H Wager (p. __): Faust bets on cyclicality, as opposed to stop-time. What does the cyclicality theme imply about this particular story? Salvation GRETCHEN STORY The Gretchen story is entirely new in Goethe’s version. “In two important ways it introduced a perspective which was entirely removed from the traditional Faust and which addressed central concerns of later eighteenthcentury thought. First, the theme of seduction, a preoccupation of the age, as we saw in Don Giovanni, was united with the essential dynamic power of will in Faust, his striving for infinite knowledge and experience. Second, a dimension of social realism was introduced to Faust which carried profound legal and moral implications for Goethe’s own time. The theme of infanticide, often involving the seduction of innocent girls who subsequently fell victim to the intolerance of eighteenth-century middle-class society, usually leading to their execution while the seducer escaped without penalty, attracted many writers. Gretchen, not Faust, is the central figure of this part of the play. This part is her tragedy.”—H One of the major modes of latetwentieth-century literary analysis was Marxist criticism. Marxist critics argue that literature reflects the social, economic, and political forces in the society that creates it. One Marxist critic (Lukacs) wrote that the Gretchen story was “a glaring example of class oppression of the bourgeoisie by the nobility.” We could, of course, say the same of the Zerlina story in Don Giovanni. “The tragedy of the bourgeois maiden seduced is only one of the many abuses perpetrated by degenerate feudalism. From the standpoint of poetic creation, however, this theme has advantages such that it became, not by chance, the principal dramatic theme of the German Enlightenment. It concentrates, in a typical individual case which is easy to relive imaginatively, the most repugnant features of the oppression, features apt to rouse spontaneously to indignation the whole bourgeoisie.”—Lukacs? Gretchen’s full name is “Margarete.” Her naming may have been a response to the execution for infanticide of a Susanna Margarethe Brandt in the city where Goethe was living and in the year before he began writing Faust.—H VALENTINE STORY Great myths often share common resonant elements. In relation to the other modern myth we have seen, Valentine assumes the role of the Commendatore, and the serenade is reminiscent of that “which Don Giovanni, disguised as Leporello, sings beneath the balcony of Donna Elvira in Act II, accompanying himself on a guitar, as he attempts to seduce Donna Elvira’s servant girl. It is interesting to note that the role of Don Juan in both its aspects is assumed more by Mephistopheles than by Faust, first when he sings the song beneath Gretchen’s window, then when he manipulates the sword which kills Valentine.”—H There was, of course, no devil to take much of the rap for Don Giovanni. Faust, while obviously heavily flawed, is certainly the nobler figure. P. 137, ll. 89-90: The editors of your anthology use this same word, “spectacle,” on p. 133 to describe the actual production of Faust. ll. 99-103: Ironic, considering the performance history “Gretchen am Spinnrade” (p. 195) “Erlkönig (p. 251) MCD 2515 ERLKING “Caught between his father, a rationalist eager to dispel the mysteries of nature, and the seductive Erlking, the child recognizes the dangers acutely but is powerless to ward them off. The father and the Erlking, indeed, can be taken to personify the tensions tearing apart the child’s heart. Typical of Goethe are the concluding nearly monosyllabic understatements—the child’s last phrase ‘has done me harm’ [hat mir ein Leids getan] and the equally spare conclusion ‘the child was dead’ [das Kind war tot]: these may be felt to protect against the power of the emotion and, at the same time, to keep it in reserve, like a coiled spring. In Franz Schubert’s famous setting of the ballad, the child’s last phrase is virtually screamed, pounding out the terror the poetry magnificently understates. Conversely, Schubert sets the end of the poem as a spare, lowpitched, unaccompanied recitative, the bare bones left after nature has seized the child back unto itself.”—Damrosch “In the ‘Erl King,’ it is neither the melodic expression nor the succession of notes in the voice-part which gives organic unity to the whole, but rather the harmonic expression, the tone, imparted to the work by the accompaniment. This is the foundation here, on which the tone-picture is laid, and indeed quite in accordance with the text, where night and tempest and the father on horseback with his child compose the background. With profoundly moving truth the melodic expression characterizes the inner meaning of the action, the changing emotions of the father, the child and the erl king, while its outward aspects, such as the galloping horse and the intermittent howling of the gale, are outlined by the most appropriate figures of accompaniment. Such a treatment was the only possible one in this case, since the uniform romance-like tone of the poem demanded a similarly uniform tone in the musical representation. In order to weave this tone into the whole, without sacrificing anything of the necessarily different characteristics in the words of the acting exponents, the separate melodies, the disparate parts of the significant vocal expression, had to be unified by the accompaniment. The latter thus did not serve as a foil to the voice-part, but also as musical painting outlining the atmosphere.”—early review GRETCHEN AM SPINNRADE Gretchen’s “state of mind, in which the feelings and sensations of love, of pain and of rapture take turns, are so affectingly depicted by schubert’s music that a more heart-stirring impression than that left by his musical picture is scarcely imaginable. Apart from that, the composition is also remarkable for its pianoforte part, which so successfully sketches the motion of the spinningwheel and develops its theme in such a masterly way.”—early review