CHAPTER 12

The Presidency

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, students should be able to do the following:

1.

Define the key terms at the end of the chapter

2.

List the powers and duties of the president as set forth in the Constitution

3.

Describe the sources of power outside the Constitution that presidents have used to expand the

authority of the office, including congressional delegation of powers

4.

Outline the components and duties of the offices that make up the Executive Office of the

President

5.

Identify the three advisory systems that support the president and give an example of each

6.

Explain why modern presidents are more likely to rely on the White House staff than on the

cabinet for advice on policymaking

7.

Define and discuss the various aspects of a president’s ability to persuade

8.

Explain why presidential popularity usually declines while a president is in office

9.

Explain why there is often divided government, and tell how it affects the president’s ability to

carry out his perceived mandate

10. Explain what is meant by describing the president as “chief lobbyist”

11. Compare and contrast specific features of the U.S. president against those of the prime minister of

Great Britain

12. Discuss the changes that are now occurring in the president’s role as a world leader

13. Identify four objectives of the president in international relations and foreign policy

14. Describe the special skills presidents need for crisis management

CHAPTER SYNOPSIS

War, and a president’s ability to engage the United States in it, still causes arguments about many of the

same things that the authors of the Constitution debated. The powers of the presidency still concern us.

What powers belong to the president? Although some are quite clear from the Constitution, claims of

inherent powers have led to many controversies during our history. How past presidents have expanded

the powers of the office is key to understanding the nature of the modern presidency.

In exercising leadership, the president has the resources of the executive branch to draw on. None of

these is more important than his personal staff. More broadly, he draws upon the Executive Office of

the President and his cabinet. The task of presidential leadership is to translate a political vision into a

concrete agenda and then to persuade the public and Congress to support legislation that furthers that

agenda.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 12: The Presidency

133

The president is perceived as a popularly elected leader, and his political skills are critical for putting

together a winning electoral coalition. The need to win favor with the public does not end with the

election. A president’s popularity affects his standing with Congress and his overall ability to lead.

Candidates who successfully put together an electoral coalition and win the presidency inevitably claim

to have received a mandate from the public. In recent years their ability to carry out the perceived

mandate has been made more difficult by divided control of government.

The president is a world leader, too, and his skills at crisis management and diplomacy will affect the

success of his administration. The way a president handles both crisis and non-crisis decision making in

the White House is often influenced by his “presidential character.”

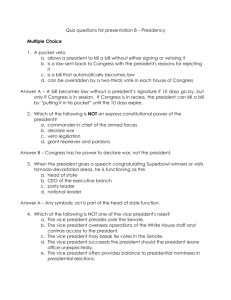

PARALLEL LECTURE 12.1

I.

II.

The Constitutional basis of presidential power

A. Initial conceptions of the presidency

1. Delegates to the Constitutional Convention were wary of unchecked power.

a) The Articles of Confederation had failed in part because of lack of a strong

national executive.

b) Task: provide national leadership without the opportunity for tyranny.

2. Delegates initially approved a single executive chosen by Congress for a seven-year

term, ineligible for re-election.

3. Final structure reflected “checks and balances” philosophy

B. The powers of the president

1. Requirements for the presidency

a) U.S.-born citizen

b) At least thirty-five years old

c) Have lived in the United States for at least fourteen years

2. Duties and powers of the president

a) Act as administrative head of the nation

b) Act as commander in chief of the military

c) Convene Congress

d) Veto legislation

e) Appoint various officials

f)

Make treaties

g) Grant pardons

The expansion of presidential power

A. Formal powers

1. Constitution involves president in policymaking process through veto power, reporting

to Congress on state of the Union, and role as commander in chief

2. Presidents have become more aggressive in their use of these powers.

a) Much greater use of veto power over time

b) Expected that presidents will enter office with clear policy goals and work with

Congress to pass legislation

c) Presidents use commander in chief power to enter into foreign conflicts without

formal declaration of war.

B. Inherent powers

1. Inherent Powers: authority claimed by the president that is not clearly specified in the

Constitution; typically these powers are inferred from the Constitution.

a) Forces Congress and the courts to either acquiesce or restrict action

b) Success in claiming a new power leaves legacy of permanent expansion of

presidential authority.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

134

Chapter 12: The Presidency

2.

Executive orders: presidential directives that create or modify laws and public

policies, without the direct approval of Congress.

a) Power to issue an executive order not explicitly granted in Constitution

b) Presidents issue orders by arguing they may take actions in the best interest of the

nation so long as they are not directly prohibited.

c) Executive orders are issued for a wide variety of purposes.

d) Important policymaking tool for presidents

e) Allow the president to act quickly and decisively

f)

May be overturned by congressional bill or court challenge

3. Executive agreement: similar to executive order, but used in foreign policy.

C. Congressional delegation of power

1. Delegation of powers: the process by which Congress gives the executive branch the

additional authority needed to address new problems.

a) Example: Congress delegated power to FDR to deal with the problems of the

Great Depression.

b) Used when Congress concludes government needs flexibility in its approach to a

problem

2. Congress can enact legislation to reassert Congressional authority.

III. The executive branch establishment

A. The Executive Office of the President

1. The president depends heavily on key aides.

a) Many in the inner circle are longtime associates.

b) White House Office: the president’s personal staff.

c) Chief of Staff: may be first among equals or the unquestioned leader of the staff.

d) National Security Adviser: provides daily briefings on foreign and military

affairs.

e) Council of Economic Advisers: reports on the state of the economy and advises

how to promote economic growth.

f)

Senior domestic policy advisers: advise on health, education, and social services.

2. Below the top aides are the large staffs that serve them and the president.

a) Executive Office of the President: the president’s executive aides and their

staffs; the extended White House executive establishment.

b) Includes the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and other specialized

staff

c) Employs almost sixteen hundred people; annual budget $374 million

3. Major types of presidential advisory systems

a) Competitive management style (example: FDR)

(1) Advisers have overlapping authority and differing points of view.

(2) Allows president to hear all sides of an argument and still be the final

decision maker

b) Hierarchical staff model (example: Eisenhower)

(1) Clear lines of authority; mirrors military command

(2) President does not participate in details of policy discussion

c) Collegial staffing arrangement (example: Bill Clinton)

(1) Loose staff structure that gives many staffers access to the president

(2) Immerses president in the details of policymaking

d) Presidents tend to choose system that best suit their personality

e) Most presidents use a combination of styles.

f)

Presidents must ensure staff members feel comfortable telling him things he

doesn’t want to hear.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 12: The Presidency

(1)

135

Groupthink: when staffers reach consensus without considering all sides of

an issue.

(2) Not easy to tell the president he is misguided

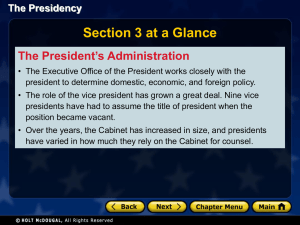

B. The vice president

1. Most important duty of vice president is to take over the presidency in case of

presidential death, disability, impeachment, or resignation

2. Has traditionally carried out political chores: campaigning, fundraising, etc.

a) Often vice presidential selection have more to do with politics

b) Vice presidents are often chosen because they appeal to different geographic

region or party coalition than the president

3. Trend toward presidents relying more heavily on vice presidents in policymaking

C. The cabinet

1. Cabinet: a group of presidential advisers; the heads of the executives departments, and

other key officials.

2. Has expanded greatly, reflecting increased government responsibility and intervention

3. The cabinet is not used as a collective decision-making body.

a) Cabinet is rather large

b) Most cabinet members have limited areas of expertise and cannot contribute to

the discussion in other areas.

c) President chooses cabinet members for a range of reasons, not necessarily

because they are close to him

d) The White House staff offers most of the advisory support the president needs.

e) Cabinet secretaries may be pulled in different directions by the president and by

their clientele groups.

IV. Presidential leadership

A. Leadership is a function of president’s own character and skill and the current political

environment

B. Presidential character

1. Difficult to judge character, but it does matter

a) LBJ: feared his masculinity being questioned, so did not exit Vietnam

b) Nixon: fear of “enemies” nurtured climate that created Watergate break-in and

cover-up

c) Clinton: actions with Monica Lewinsky led to impeachment, but not conviction

2. Voters claim to care about traits like competence, integrity, and empathy.

C. The president’s power to persuade

1. Neustadt, Presidential Power: “Presidential power is the power to persuade”

a) Presidents must depend on others’ cooperation to get things done.

b) Critical presidential abilities

(1) Bargaining

(2) Dealing with adversaries

(3) Choosing priorities

2. President’s political skills can affect outcomes in Congress

a) Presidential influence takes place “at the margins.”

b) Can be enough to affect the outcome of closely fought legislation

3. President’s influence is related to professional reputation and prestige

a) If Congress defeats or weakens a priority bill, president’s reputation is hurt

b) Controversial bills are a big risk.

D. The President and the public

1. A popular president is more persuasive than an unpopular president.

a) Public support is a resource in the bargaining process

b) Members of Congress have more incentive to cooperate with a popular president.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

136

Chapter 12: The Presidency

2.

V.

Efforts to mobilize public support

a) Televised addresses, remarks to reporters, and public appearances allow the

president to speak to the people.

b) “Going public”: situations where the president forces compliance from fellow

Washingtonians by going over their heads to appeal to constituents.

3. Presidents pay close attention to their standing in public opinion polls.

a) “Honeymoon period”: the first year a president is in office, when approval ratings

are their highest.

b) Presidents with low approval ratings at re-election time tend not to win reelection.

4. Fluctuations in presidential popularity

a) Public approval is affected by economic conditions.

b) President is affected by major events that occur during his presidency.

c) Presidents typically lose popularity when involved in a war with heavy casualties.

5. Leading by courting public opinion has considerable risks.

a) Presidents are left vulnerable if support does not materialize.

b) Also need to be able to form bipartisan coalitions and broad interest group

coalitions

6. Concern with public opinion can be defended as furthering majoritarian democracy.

E. The political context

1. Partisans in Congress

a) One of the best predictors of presidential success is the number of fellow

partisans in Congress.

b) Divided government: the situation in which one party controls the White House

and the other controls at least one house of Congress.

(1) Scholars generally don’t think divided government produces gridlock: a

situation in which government is incapable of acting on important issues.

(2) Strong tradition of bipartisan policymaking in Congress

2. Elections

a) By running for office, candidates align themselves with particular segments of

the population.

b) Candidates try to win votes from different groups through their stands on various

issues.

c) The winning candidate wants to claim a mandate: an endorsement by voters;

presidents sometimes argue they have been given a mandate to carry out policy

proposals.

3. Political party systems

a) Presidential leadership related to the president’s relationship to the dominant

political party and its policy agenda

b) Skowronek: leadership depends on president’s place in cycle of rising and falling

governing coalitions.

c) Presidents who come to power right after critical elections have the most

favorable environment.

The president as national leader

A. From political values…

1. Presidents differ greatly in their views of the role of government

a) LBJ: focus on equality and inequality

b) Ronald Reagan: focus on freedom

2. Not all presidents move so strongly toward one ideological position or another.

B. … to policy agenda

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 12: The Presidency

1.

137

Roots of particular policy proposals can be traced to more general political ideology of

the president

2. Newly elected president must make hard choices about what to push for

3. President’s role in legislative leadership is a twentieth century phenomenon

C. Chief lobbyist

1. Over time, presidents have become increasingly active in all stages of legislative

process

2. President’s efforts are reinforced by work of legislative liaison staff

a) Legislative liaison staff: those people who compose the communications link

between the White House and Congress, advising the president or cabinet

secretaries on the status of pending legislation.

b) Advise on problems that emerge and what a bill’s chances of passage are with or

without certain provisions

c) Tries to build consensus by working cooperatively with legislators

3. White House also works directly with interest groups to build support

a) Interest groups quickly reach constituents who are most concerned about a bill.

b) Lobbies tend to be granted access to the president only when the White House

needs them to activate public opinion.

4. When agreement cannot be reached, president may veto a bill and send it back to

Congress

D. Party leader

1. President has informal duty to lead his party

2. President and members of his party in Congress can take very different positions on

issues

3. President is “fundraiser in chief” for his party

a) Strong incentive to raise money for congressional candidates

b) Legislators are grateful for president’s assistance

VI. The president as world leader

A. Foreign relations

1. For forty years, the president’s priority as world leader was to contain communism.

2. American presidents have entered a new era in international relations.

3. Four fundamental objectives

a) National security: the direct protection of the United States and its citizens from

external threats.

b) Fostering a peaceful international environment

(1) Working with the U.N. and NATO

(2) Mediating conflict and facilitating bargaining

(3) Participating in multinational military peacekeeping forces

c) Protection of U.S. economic interests

(1) Must balance many conflicting interests

(2) Case of normalizing trade relations with China highlights conflicts

d) Humanitarian concerns and the protection of democracy throughout the world

(1) United States may impose trade sanctions to discourage human rights

violations

(2) May sent troops to support transition to democracy

B. Crisis management

1. The president may face a grave situation in which conflict is imminent or a small

conflict threatens to explode into a larger war.

a) How a president handles such crises is critical to the success of his presidency.

b) Citizens may vote for candidates who project careful judgment.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

138

Chapter 12: The Presidency

2.

3.

4.

Kennedy’s behavior during Cuban missile crisis has become a model of effective crisis

management.

Guidelines for crisis management

a) Draw on a range of advisers and opinions

b) Do not act in unnecessary hast

c) Have a well-designed formal review process with thorough analysis and open

debate

d) Rigorously examine the reasoning underlying all options to assure that

assumptions are valid

Guidelines do not guarantee against mistakes; crises are unique events.

INTERACTIVE MEDIA LECTURE 12.1 “THE DRAMA OF THE

PRESIDENCY”

The American President

There are numerous movies that either feature or rely on the character of the American president. This

lecture can easily be adapted to many of these—indeed, it may even be helpful to highlight this feature

in the media by showing clips from several films and/or television shows. The primary task of this

lecture is asking students to consider what is gained and what is lost when we focus on the presidency

as a “personal” institution.

The American President (1995) is the story of widower/father/President Andrew Shepherd (Michael

Douglas), an unabashedly liberal Democrat, who is just gearing up for re-election when he meets an

attractive and sharp environmental lobbyist named Sydney Wade (Annette Bening). The two fall in love

and the president must soon deal with the political repercussions (Sydney is trying to get legislation

through Congress), as well as the cynical machinations of Republican opponent Senator Bob Rumson

(Richard Dreyfuss), who attempts to paint Sydney as a radical and use “family values” rhetoric to smear

Shepherd. With the attacks affecting his standings in the all-important polls, and his love’s legislation

causing him headaches in the Capitol, Shepherd must decide whether he can risk continuing his

relationship.

The scenes referenced here highlight the tensions that adhere to being both the president and a man who

has lost his wife and has begun dating again.

DVD: begin at Chapter 14, “Got a Girlfriend”, run to 59:30 (when Sydney shows up at the White

House to break up with the president)

Tape: begin at 48:30, run to 59:30 (when Sydney shows up at the White House to break up with the

president)

(NOTE: There are several other scenes in this movie that could be used to similar effect; please screen

the movie in its entirety to determine if it would be effective for you to use additional footage.)

I.

II.

“What you did tonight was very presidential”: presidential power in the movies

A. Review of the formal and inherent powers of the presidency

B. What presidential powers and responsibilities were highlighted in this clip?

Presidential leadership

A. What qualities of character do Americans look for in a president?

1. How does this play into the electoral process?

2. What “special circumstances” might impact the typical construction of presidential

character?

B. What do we know about the president’s powers of persuasion?

C. What do we know about how the president would tend to manage a crisis?

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 12: The Presidency

139

D. How are these aspects of the presidency portrayed in this clip?

III. The president as a dramatic character

A. Do we have any reason to believe the day-to-day presidency is as dramatic as the movies (or

television) portray?

B. How do Americans benefit from dramatic portraits of the presidency, such as this one?

1. Learn more about the structure of the executive office?

2. Learn more about the challenges presidents face?

3. Learn more about the humanity of the president—even if we happen to disagree with

his policies?

4. What are some other benefits of dramatic portraits of the presidency?

C. How are Americans disadvantaged by dramatic portraits of the presidency, such as this one?

1. Develop a tendency to over-personalize the presidency—forgetting about the large

number of people that make the executive branch work?

2. Lose respect for the complexity of real issues because drama requires issues to be

settled quickly to maintain pacing?

3. Minimize the differences between real politics and fiction, since the medium in which

most of our political takes place is also our entertainment medium?

4. Develop expectations of the presidency that are unrealistic?

FOCUS LECTURE 12.1

The President and His Staff

How well a president does in office depends in part on how well he uses the resources of his office. One

of his most important resources is the staff at his disposal.

I.

Cabinet government

A. When we think of the presidency, it is easy to conclude that chief executives have an

excellent advisory system in their cabinets. Although presidents depend heavily on some

members of their cabinets, they do not depend on the cabinet as an advisory body.

1. Some of a president’s cabinet appointees are people he does not know well.

2. Cabinet members can easily become ambassadors from their constituencies. The

secretary of agriculture, for example, may come to feel that his or her job consists as

much of representing farmers before the president as it does of representing the

president to farmers.

3. As a body, the cabinet is quite large. Including top presidential aides and individuals

with cabinet rank (such as the ambassador to the United Nations), this group numbers

more than twenty people. Presidents may not find this size conducive to decision

making.

B. For these reasons, talk of “cabinet government” in the United States is just that—talk.

Cabinet meetings have been disparaged as “vapid nonevents in which there has been a

deliberate nonexchange of information as part of a process of mutual nonconsultation.”

Griffin Bell, Jimmy Carter’s attorney general, described cabinet meetings as “adult showand-tell.”

C. Still, individual cabinet members do become key advisers to the president. Some examples

are Robert Kennedy, attorney general in the Kennedy administration; John Mitchell, attorney

general in the Nixon administration; and Henry Kissinger, who after serving as Nixon’s

national security adviser was secretary of state to both Nixon and Ford.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

140

Chapter 12: The Presidency

II.

Presidential decision making

A. Presidents need advisers because they must continually make policy decisions on

complicated and controversial issues. They do not have time to study thoroughly each issue

that comes before them.

B. Often the information on an issue will be boiled down to a memorandum for the president’s

reading. He may formally make his decision by checking a box at the end of the memo.

C. On major issues—arms control negotiations, for example—he holds talks with his major

military and foreign policy advisers to go over the pros and cons of different policy options.

D. A president is dependent on his staff to summarize and analyze the available information in

an objective manner. The president must trust his key aides and cabinet officials to present

him with all the available alternatives.

III. Staff infections

A. Presenting the president with all the alternatives and the pros and cons for each may sound

like a relatively simple procedure. Yet problems abound with the presidential advisory

system.

1. One problem that may emerge is that the staff can shut the president off from people he

should be listening to. Access to Richard Nixon was very tightly controlled by his top

aides, and some officials who had opinions that seemed out of line with the dominant

view of the administration had a difficult time getting in to see Nixon. A president

should hear a range of views, however.

2. Another potential problem is that top staffers know the president’s views so well that

they may anticipate what he wants to hear and may be predisposed to recommend

those solutions to him. Certain options may be eliminated because staffers assume the

president will never go for them. Yet sometimes those excluded options will be the

ones that should have been followed (and may eventually be followed).

3. Aides may also do a president a disservice when they work out a compromise solution

to a problem and present it to the president as their consensus. The chief executive

might be better served if he heard the arguments for all the alternatives. The

compromise solution is not necessarily the best one.

B. It is important to remember that a president makes the basic decisions about how his staff is

to be structured. Some presidents don’t like to hear the views of those who disagree with

them. This may result in decisions flawed by lack of thorough discussion. Other presidents,

such as Clinton, want to hear so many views that the decision-making process may be

terribly delayed.

C. Again, we recognize the central problem: the president does not have the time to analyze

thoroughly every single issue that comes before him. Limited time means that some

decisions must be made on the basis of limited information.

IV. The advisory system structure

A. Inner White House staffs are structured in two basic ways:

1. The strong-chief-of-staff model—some presidents, like Eisenhower, Nixon, and

Reagan in his second term, have given one adviser at the top of the staff hierarchy

considerable authority. That person largely controls access to the president.

2. The spokes-of-the-wheel model—the president is the hub and the advisers are the

spokes spreading out from the hub. Each “spoke” has direct access to the president.

This type of system was used by John Kennedy, Jimmy Carter, and, in modified form,

by Bill Clinton.

a) At first glance, the spokes-of-the-wheel model may seem best, because it works

against some of the problems described earlier. However, it, too, has problems.

As former presidential aide Stephen Hess points out in Organizing the

Presidency (the revised ed., Washington, DC: The Brookings Institute, 1988), the

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 12: The Presidency

B.

C.

D.

141

more aides there are in the White House, the greater the number of problems that

will come into the White House.

b) In Hess’s mind, White House staffers act as “bridges” from the bureaucracy. The

more bridges that are open, the more “traffic” will come in over them. The

president (and his top staffers) may be caught up in making so many decisions for

the executive branch that they don’t have enough time to think about the big

picture. Larger questions of leadership may be put aside as the imperatives of

day-to-day decision making take over.

Presidents sometimes go outside their immediate staff or the larger executive branch

establishment to ask the advice of outsiders. A president will also on occasion set up an

outside task force to study a problem and recommend policy changes. (Sometimes

commissions are appointed to try to defuse criticism, not because expertise is inadequate or

objective analysts are unavailable within the executive branch.)

1. Franklin Delano Roosevelt tried to protect himself against the kind of staff pathologies

described earlier by giving the same assignment to different staff members. Arthur

Schlesinger, Jr., wrote, “His favorite technique was to keep grants of authority

incomplete, jurisdictions uncertain, charters overlapping. The result was a competitive

theory of administration.”

2. It is not easy to set up a staff system to operate efficiently in this manner. Overlapping

jurisdictions can lead to infighting, as happened between the Ed Meese staff and the

James Baker staff during the first Reagan term. Efficient administration usually implies

clear lines of authority; likewise, duplication and overlap tend to indicate wastefulness.

No organizational chart, no matter how thoughtfully drawn, will save the president from

being ill-advised at times. In the last analysis, the president himself will decide how he will

use his advisers and whose judgment he trusts the most.

If there is a good rule to follow, though, it is that the president should expose himself to

conflicting viewpoints. He should hear those opinions from their strong advocates.

FOCUS LECTURE 12.2

The Presidency and Psychohistory

This lecture explores the use of psychoanalytic theory in explaining presidential character and behavior.

I.

II.

Examining presidential personality and character

A. When we examine the leadership qualities of presidents, it is useful to go beyond the

evaluation of their abilities.

1. It is, however, a difficult and murky task to examine their personality traits.

2. The premise for studying the personalities of presidents is simple: presidents are

human beings; they have inner conflicts just as the rest of us do.

B. Individual personality traits can shape a president’s behavior; that is, his political decisions

will be affected by his inner feelings. A president’s psychological needs may be manifested

in very strong ways in his public duties.

C. Indeed, a president’s psychological needs may sometimes push him toward wrong decisions

as he carries out his duties in office.

Woodrow Wilson

A. The example of Woodrow Wilson’s behavior in office is fascinating to those who view the

presidency through the prism of personality.

1. Wilson believed that God put him on this earth to do certain things.

2. When you’re doing God’s work, it’s difficult to compromise. Does one compromise

with the will of God?

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

142

Chapter 12: The Presidency

3.

James David Barber notes that when Wilson was asked if he was ever wrong, he

replied, “Not in matters where I have qualified myself to speak.”

B. We can see Wilson’s adherence to “God’s will” and his unyielding, uncompromising

manner in his fight for the League of Nations. He obstinately refused to make the

compromises that would have at least given the League a better chance, whereas it was

otherwise clearly doomed. But Wilson fought on, stopped only by a stroke.

C. Wilson’s single-minded approach was not limited to his fight for the League of Nations. As

Alexander George and Juliette George recount in Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House (NY:

Dover Publications, 1964), Wilson behaved in a similar way when he was president of

Princeton University. In a fight over where to locate the graduate school, he was stubborn

and uncompromising.

D. Wilson’s behavior in connection with the League of Nations and the Princeton graduate

school are manifestations of his psychological responses to other events in his life. What

were the root causes?

1. We have no precise answers. We don’t have the notes or interpretation of an attending

therapist. We must rely on psychohistory—psychological interpretation of historical

records.

2. Historians and political scientists point to Wilson’s relationship with his father, Joseph

Wilson, who was very demanding of his young son. Joseph Wilson was a harsh,

unloving man who thought that criticizing his son’s behavior was the key to making

him a person of character. Woodrow Wilson’s daughter, Margaret, told her father’s

biographer that Joseph Wilson’s idea was that “if a lad was made of fine tempered

steel, the more he was beaten the better he was.”

3. Biographers Alexander George and Juliette George write, “Wilson’s own recollections

of his youth furnish ample indication of his early fears that he was stupid, ugly,

worthless and unlovable. It is perhaps to this core feeling of inadequacy and of a

fundamental worthlessness which must ever be disproved.” They argue that his need

for “affection, power, and achievement” as well as his “compulsive” quest for

perfection may be traced to the difficult relationship with his father.

III. Lyndon Johnson

A. It is common for adults to still be striving for accomplishments as a way of proving their

worth to their parents. Yet we don’t have the kind of data about presidents to prove that they

are the way they are because of some event that happened in childhood.

B. We do know from psychology, however, that adult behavior can often be correlated with

childhood experiences. Experiences as a young adult can also be important. Lyndon Johnson

offers another example of a strained relationship with a father. Again, we can consider

whether this biographical fact offers a cogent explanation of Johnson’s behavior as

president.

C. Robert Caro’s masterful biography of the young Lyndon Johnson, The Path to Power (NY:

Vintage Books, 1983), paints a picture of a troubled relationship between Lyndon and his

father, Sam. Our account is drawn from the Caro book.

1. As a young man, Johnson was trying to find himself. He did not have a good

relationship with his father, and he felt that he had disappointed his mother. At age

seventeen, he left Texas for Nevada to work as an apprentice for a lawyer. He left

shortly thereafter and came back to Texas.

2. Caro says that a critical juncture in Johnson’s life came after he had returned to Texas.

He was leading a rough-and-tumble life and had chosen not to go to college. His

parents were disappointed and were not happy with how he was leading his life.

3. At a dance he attended with some cousins, he was attracted to a pretty blonde girl and

decided that he was going to take her away from her boyfriend, Eddie. He danced with

the young lady, but soon Eddie asked Lyndon to step outside. Lyndon’s cousin Ava

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 12: The Presidency

143

told Caro that Eddie beat Lyndon mercilessly. Lyndon kept getting knocked down until

“blood was pouring out of Lyndon’s nose and mouth, running down his face and onto

the crepe-de-chine shirt.”

4. Ava concludes, “Lyndon never got in a lick. It was pitiful. Every time he got up, that

old boy knocked him down. Lyndon’s whole face was bloody, and he looked pretty

bad. And finally, lying on the ground, he said, ‘That’s enough.’”

D. Caro ruminates on this. Is it possible that Lyndon’s “That’s enough” was a response to his

parents as well as to Eddie? Was it a “surrender” to his parents’ wishes? There is no way of

knowing for sure, but the next morning Lyndon told his parents that he would go to college.

E. It’s quite a jump to go from a dance hall fight to his behavior as president. Was our

disastrous stay in Vietnam a reflection, in part, of Johnson’s need to prove his manhood?

1. Another Johnson biographer, Doris Kearns Goodwin, argues that Lyndon Johnson

“was not forced to see himself as a coward, running away from Vietnam.”

2. Is this persuasive, or is it no more than mere speculation?

IV. Bill Clinton

A. Bill Clinton was the subject of psychohistorical analysis during his first year in office.

B. The Journal of Psychohistory (Winter 1994) had a special issue on “Clinton’s America.”

C. The general theme was that much of Clinton’s presidential style and policy priority list were

products of his early life experiences.

1. Clinton lost his father before his birth and spent his formative years with grandparents

while his mother struggled to get an education.

2. When he was reunited with his mother, he wanted to please her and protect her from

his alcoholic stepfather.

3. Clinton’s image as a waffling liberal is related to the desire of a child in a

dysfunctional family to keep everyone happy. He therefore finds it is difficult to say no

to anyone.

D. Clinton’s approach to policy issues such as health care, foreign policy, taxation, and public

investment show signs of his struggle to stay focused and committed.

E. Clinton justifies his many compromises as realistic Washington politics. But critics suggest

that a different personality type might handle the same pressures differently and compromise

less.

F. Clinton also has a generational battle to contend with: he is a product of the baby boom,

feminism, and 1960s antiwar attitudes. Having an egalitarian partnership in his marriage

makes him look weak to older men as well as to more traditional men and women.

G. Is it valuable to learn and evaluate the personal history of a president? Or is it irrelevant to

the political issues?

V. The range of work

A. The work in this area varies in quality and approach. The origins of this broad area of

scholarship are best traced to the outstanding work done by Erik Erikson.

1. Erikson, a psychoanalyst and Harvard professor, was the author of the

psychobiography Gandhi’s Truth.

2. If psychobiographies could be written about figures like these, why not about

American presidents?

B. It has become a popular genre. Richard Nixon is a favorite target. In Search of Nixon and

Nixon vs. Nixon are two such books.

C. Some of these books, like George and George’s Woodrow Wilson and Colonel House, are

rather careful, cautious studies. Others are notable for their daring (and much more

speculative) interpretations.

D. Garry Wills’ The Kennedy Imprisonment is an example of the latter. Wills dwells on the

masculinity of the Kennedy men and writes, “The Kennedy boys were expected by their

father to undertake a competitive discipline of lust.”

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

144

Chapter 12: The Presidency

1.

Wills notes that John F. Kennedy questioned the masculinity of advisers who were

opposed to the Bay of Pigs operation.

2. Isn’t it far-fetched to draw a connection between Joseph Kennedy’s attitude and his

son’s foreign policy decisions? Yet John F. Kennedy’s feelings about his masculinity

were a dominant personality trait.

VI. Barber’s typology

A. Another approach can be found in James David Barber’s book The Presidential Character

(Fourth Ed., NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1992). Barber looks at all twentieth-century presidents and

tries to categorize presidential personality types into four basic types.

B. Barber’s typology has two dimensions.

1. Active-passive: How much energy does a president put into his job?

2. Positive-negative: To what degree does a president enjoy the tasks of the office?

C. Barber draws out the implications of each type and gives examples.

1. Active-positive: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, John F. Kennedy, and Jimmy Carter. The

active-positive has “high self-esteem.” He displays a congruence between his “activity

and the enjoyment of it.” Active-positives are flexible and have an “orientation toward

productiveness.” (Possibly George Bush, Sr.)

2. Passive-positive: William Howard Taft, Warren G. Harding. The passive-positive is

“compliant.” He is “other directed” and is a personality “whose life is a search for

affection as a reward for being agreeable and cooperative rather than personally

assertive.” Barber says that passive-positives have “low self-esteem,” but at the same

time exude a “superficial optimism.” (Possibly Ronald Reagan.)

3. Active-negative: Woodrow Wilson, Herbert Hoover, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard

M. Nixon. The active-negative is “compulsive.” He works intensely at his job but

experiences relatively few rewards from it. He has a problem “managing his aggressive

feelings.”

4. Passive-negative: Calvin Coolidge, Dwight D. Eisenhower. Passive-negatives are

“withdrawn” and are oriented toward “dutiful service.” They withdraw to avoid

conflict.

D. How might Bill Clinton and George W. Bush fit into Barber’s typology?

PROJECTS, ACTIVITIES, AND SMALL-GROUP ACTIVITIES

1.

The presidency and Congress are coequal branches of government. But how equal are they in

terms of our expectations? One way to examine this is to look at press coverage of the two

branches. For a two-week period, students can measure the column inches in their local paper, or

the time on their local news, devoted to the president, to Congress, or to both jointly. How many

of the news pieces begin on the front page or in the first five minutes of the newscast?

2.

In another project that relies simply on a newspaper (in either its print or electronic version),

students can keep track of the various “hats” that the president wears during a two-week period.

Give students a list of presidential roles at the beginning of the project and have them refer to this

list when coding the articles. Alternatively, you can have students devise the list of roles as part of

their assignment.

3.

Direct your students to the White House’s Briefing Room on the World Wide Web at

www.whitehouse.gov/news/. Here students may view all of the White House’s press releases

either for the day or the entire week. Ask students to jot down a list, by topic, of press releases.

Also assign students to read the newspapers and watch the television news for the corresponding

day(s) or week. Ask students to use their knowledge from Chapters 6 and 12 to discuss the

differences between topics covered by the three venues (White House website, TV news, and

newspapers).

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Chapter 12: The Presidency

145

4.

To give students some sense of the changes in electoral coalitions over time, consider assigning

each (or having each choose) a particular presidential election to investigate. They will need to go

to the library and record the states for each of the candidates for that election. This can be done

graphically through coloring a map of the states. They should also report on the broad groups of

voters that made up each candidate’s electoral coalition.

5.

Let students use their own background knowledge to evaluate the current president. Give them

about a week’s notice so they can scan newspapers and magazines for articles about the president.

They should bring their articles to class. Then ask them to form small groups to share their

material in response to the following discussion questions: What similar themes are found in the

various articles? What biases appear in the media regarding the president? What events or

presidential actions seem to create the most media coverage? Do students feel the media cover the

most important issues? If not, why not? Do students feel the president is being treated well or

poorly by the media? What are student views of the president’s policies, including foreign policy,

domestic policy, and relations with Congress? Give the groups about twenty minutes as you

circulate to assist them. Then reconvene the class and ask for group reports on their discussions.

INTERNET RESOURCES

The President and the White House www.whitehouse.gov/

View presidential press releases, listen to radio addresses, take a virtual tour of the White House,

and browse the White House archives.

American Presidents www.americanpresidents.org/

Comprehensive history of the presidency and its inhabitants, presented by C-Span

Presidents of the United States (POTUS) via the Internet Public Library www.ipl.org/div/potus

In this resource you will find background information, election results, cabinet members, notable

events, and some points of interest on each of the presidents.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.