Rereading Sidney`s Certain Sonnets

advertisement

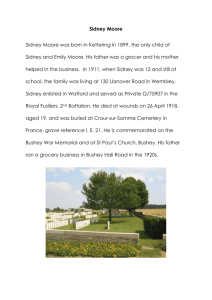

Rereading Sidney's Certain Sonnets Sidney wrote most of Certain Sonnets before 1581, during the same period he was writing the Old Arcadia and The Defence of Poesie, and immediately before he wrote Astrophil and Stella. Critics generally see the early collection of quaterzains, songs, and translations as miscellaneous juvenilia, the product of an apprentice who later composes a great sonnet sequence. Not enough attention has been given, however, to just how much of a miscellany the collection is. The few who have bothered to discuss Certain Sonnets give it only marginal status in Sidney's canon. This marginalization must be reconsidered, because Sidney's poetic career reveals constant experimentation with literary genres. He composed a playlike entertainment resembling a masque, pastoral eclogues, two versions of prose epics with verse insertions, a treatise on poetic theory, a sequence of quaterzains and songs, and a partial translation of the Psalms of David. Analysis of Certain Sonnets suggests that he also experimented with the poetic miscellany. Works that could have influenced Sidney include the 1574 edition of Tottel's Songes and Sonettes, and Turberville's Epitaphes, Epigrams, Songs and Sonets (1567) which are among the books recorded in the catalog of the Sidney family library of Penshurst Place. This links seems especially appropriate given the strong intertextual relation between these miscellanies and Astrophil and Stella.1 The attraction of the miscellany would have been obvious to a young poet, especially its ability to accommodate any number of lyric forms employing a variety of different tropes or themes. As a theorist who argues that the poet should "freely [range] only within the zodiac of his own wit,"2 Sidney would have found the miscellany the appropriate place to record his translations of Horace, Catullus, Seneca, and Montemayor, his imitations of Italian song, his experiments in quantitative verse and the sonnet. Tottel's work defined a readership willing to accommodate in the next quarter century the publication of over a dozen miscellanies.3 Mid-Tudor poets recognized that books achieved for poems "an attention or examination that they could never gain for themselves individually." 4 2 Two types of miscellanies were composed: collections of poems by various authors compiled by editors not involved in the compositions except in the capacity of publishers; and collections of "gentlemen's miscellanies," containing the personal compositions of individual poets interested in providing a public forum for their work. Sidney's collection owes allegiance to this latter type of the genre.5 A scan of Certain Sonnets shows an extraordinary variety of verse forms: 14 quaterzains, 8 songs, 5 translations, and 5 verses that scan quantitatively. Sidney includes an excusatio, an innamoramento, a complaint, poems of comparison and absence, a lullaby, a mini-sequence of four quaterzains on the nature of pain, a poem upon an impresa, a fable, a monologue, a pastoral lyric, a palinode, a poem in the patriotic genre, a song of praise and one of melancholy, a poem of rejection, a lament, and finally the commiato. The collection reads like an anthology of lyric genres whose virtuosity calls attention to itself and contrasts with all other miscellanies of the mid-Tudor period. The most complete manuscripts of Certain Sonnets, the Clifford and the Bodleian, were transcribed by professional scribes hired to write down exactly what was put before them. 6 The Clifford manuscript, transcribed in 1581, contains poems 3 to 32 following the third redaction of the Old Arcadia; and the Bodleian manuscript, transcribed in late 1581 or early 1582, contains 12, 15-21, 31, 22-28, 3-4, 6-14, after the fourth redaction of the Old Arcadia.7 The radical difference in the arrangement of poems in the manuscripts suggests that Sidney was experimenting with the structure of the miscellany. When Ponsonby published the folio edition of Sidney's poems in 1598, poems 1 and 2 of the Bodleian manuscript were attached to the order of poems in the Clifford manuscript to provide a text of 32 poems, 1--4 and 6--32. It is possible that he was advised by Mary Sidney to make this change because she recognized, as did her brother earlier, that poems 1 and 2 provided a suitable preface to a following group of lyrics on the plight of a lover. It is also possible that poem 5 was eliminated from the arrangement of the 1598 folio because of its blatant references to lust, a topic which by this time had been erased from the Sidney canon.8 One can consider -- as readers have done for some three decades -- 3 William Ringler's reconstruction of the text of Certain Sonnets, which reinstates poem 5 to the 1598 folio, as "the most complete and accurate" arrangement of poems in an early stage of the collection.9 This collection is a significant part of Sidney's compositions from 1577-1582. The arrangement of poems in Certain Sonnets appears to be based on the principle of variatio, or variety. In the classical elegaic collections with which Sidney would have been familiar poems of similar themes, or with different points of view, or about a particular experience were arranged in various locations in the text or separated by different books in the text. This disjunctive arrangement proved a source of pleasure for the reader.10 The various groups of lyrics in the body of Certain Sonnets are framed with a conventional Petrarchan innamoramento or moment of falling in love in poem 2 which is answered by the commiato, or farewell to love in 32. But the narrative which this frame implies is challenged by the loose body of poems in the middle where the lover reveals the paradoxical nature of his love. The arrangement could also be explained by Sidney's confidence that language represents the reality which it inscribes. In the Defence he theorizes that poetry is mimesis, the art of imitation, "representing, counterfeiting, or figuring forth" images of virtue and vice. 11 All but one poem in Certain Sonnets represents some variation of the lover's frenzy caused by his paradoxical desire: he is as enthralled by the virtue of his mistress as he is impelled to seek sexual fulfillment with her. In the final sections he describes his paradoxical dilemma with the rhetorical devices of apophasis and aporia which emphasize the unending conflict between the spiritual and secular worlds. What is paradoxical for Sidney is desire itself, which cannot be separated from the language in which it is expressed. What needs to be done more rigorously, and what the following argument initiates, is an examination of how Sidney's paradoxes occur at those points in the text where language undermines itself by questioning its own assertions. In the end, we have a text which contributes to its own deconstruction by inscribing the message of the incompatability between the secular and the sacred worlds.12 II 4 The consistent thematic obsession of the lover's plight in the 32 poems of Certain Sonnets is reinforced by the presence of narrative voices in individual poems. Though each lyric in the collection is self-contained and separate, each is also prompted by its immediate context. Quaterzains, songs, translations, complaints, and an impressive array of other genres each define a particular amorous concern to the reader, but, as part of an aggregate of poems, they engage in the dynamics of textual play. Juxtaposition of the poems ensure that these multiple lyric voices record the lover's paradoxical desire for sexual consummation and spiritual fulfillment. In this way Sidney constructs a textual space in which the anxiety of compulsive desire engages in a rhetorical battle with its implacable negation. Sidney's interest in narrative voices is revealed in his technical experiments in the psalms, which may have been translated during this early period. In his reworking of the first forty three psalms, he employed a different stanza form for each psalm whose uniqueness helped to construct text of separate human voices "singing God's praises."13 As well, in the eclogues of the Old Arcadia each poem is written in the first person employing voices of different people and establishing "fictive personalities ... from which Sidney could distance himself."14 Tracking the narrative voices in Certain Sonnets is possible in an analysis of the thematic links among poems. These voices attempt to disrupt and undermine the plight of the Petrarchan lover which evolves from reckless infatuation to religious conversion. The lover is introduced in the excusatio of poem 1 and the innamoramento of poem 2, but Sidney's modification of these lyric genres reflect the ambivalence of the lover's mind. In 1, the excusatio is hardly about love at all, but a verbal contract specifying the terms of an affair as an negotiated agreement: "I yeeld, o Love, unto thy loathed yoke." If his beloved ignores him, however, the lover reserves the right to withdraw his affection honorably. The aggressive voice in poem 1 is then followed by the passive and diffident voice in the innamoramento: "Longing to have, having no wit to wish," he remains, at the end of quaterzain 2, "starving" for "Cupid's dish." The conflict between desire and virtue increases in the following groups of poems. After the innamoramento, the first 5 half of the collection is comprised of four sub-groups: four songs, 3 to 7, divided by the quantitative verse of 5, four quaterzains, 8 to 11, three translations, 12 to 14, followed by three sonnets, 15 to 16. In the second half of the collection, quaterzains are outnumbered by more than two to one, as the voice of reason gives way to the more erotic and mournful songs which articulate the spontaneous resolve of the lover's irrepressible desire. If poems 3 to 7 include poem 5, as in the Clifford manuscript, they characterize the lover's sensual imagination as it confronts the prospect of virtuous love. In song 3, the lady is a typical Petrarchan mistress, both "chaste and cruell," and unable to "pitie" him, though "her eyes give to my flames their fuell." Her chastity triggers a violent response in song 4 where the impulsive pitch of the lover's erratic mind is expressed in a mournful complaint on the rape of Philomela. The song ends in the outrageous claim that the lover's predicament is even more unjust: "Since wanting is more woe then too much having" (20). Philomela has no real "cause of anguish," he concludes, for at least she has experienced love, so that her "earth now springs," where the poet only feels the absence of love in his "dayly craving" (17-18). Poem 5, the crux of this group, recalls the painful events that lead to the separation of the lovers and evokes the fantasy of sexual union still imagined possible by the poet-lover. In stanza two the lover laments the absence of love: "Where bee now those Joyes that I lately tasted?" The discovery of his "vayne worde" has assured his ruin, and now that he owes "due allegiance" to his beloved (15), he rebels against the death that that implies a violence reminiscent of song 4. He will resort to force to enjoy her again if necessary: "Duty must bee broken, / Yf Duety kill mee" (20). What follows in the penultimate stanza is a description of the lover's fantasies of sexual fulfillment: "Then come, O come, then do I come, receyve [mee],/...But between those armes, never else do leave mee." Poem 5 is also the crux of the entire miscellany. The joy once experienced between these two lovers, the language misused by them that leads to their separation, and the desire to reclaim what is now lost are variations on the theme of lost love which obsess the lyric voices in the groups of poems to follow. 6 After such psychological exertion, the lullaby of song 6 is a fitting complement. Rest does not follow, however, when the poet allegorizes his beloved into "nurse Beautie" and his "Desire" into the "babe." When she gives him her pap, the babe cries in refrain: "thy love doth keepe me waking." Poem 7 claims a spiritual dimension for the beloved: "Heaven," he says, "In thy face I plainly see." He recognizes that the power of virtue in her could transform him, that the "just accord" in which she excels could ensure that he "grace obtaineth," even if it were only while "thy face I plainly see." And this is his problem in these poems; he is as spiritually attracted to her as he is erotically attracted to her. In the second group of poems, he meditates the mortal nature of his beloved when his vision of her as "heaven" gives way to her suffering the pains of "hell." "Pain" is a monster from hell that "harbers in her face" and hopes to enjoy the beloved "with her beames wrapping his cruell staines," assuming the position as lover fantasized by the poet in song 5. In the sestet of quaterzain 9, "paine" overhears the poet's praise and "flies to her" full of "inward fire" and "bolden desire." In 10 the treatment of his lady becomes more sadistic as the couplet recalls the myth of Philomela in song 4 and enlists the support of "pain" to silence his lady's tongue so that she cannot refuse him: "So stay her toung, that she no more say no." In quaterzain 11 the lover comes full circle by recalling to what extent she has been the source of his pain. Though she "hath yet such health" in that "perfect place" which can save his life, still he is outraged because while he pities her, she only disdains him. The moral deprivation of the lyric voice at the end of the second group of poems is followed by three translations from Horace, Catullus and Seneca. Christopher Martin suggests that these poems are "touchstones" because they clarify Sidney's condemnation of physical desire by espousing "an ethos of neo-Roman practicality" in which the "ideal of moderation" is distinguished from the excesses of courtly passion.15 But a rereading of these translations reveals a shifting pattern of response to love which has become familiar by now in this collection. Though moderate by comparison to the preceding poems, the themes of the translations are overtly concerned with the sexual politics of human relations. Poem 12 modifies Horace's 7 celebration of the moderate life with images of the ambivalence of the human existence and the problems of love. The allegorical topos of the ship sailing the high seas defines the natural uncertainties of human existence. One should "draw in" the "swelling sailes" and show restraint, we are told, when the storm proves too threatening. Caution gives way to pessimism, however, when in 13 even the prospect of good faith in a marriage between the lover and his lady is not assured. Though she swears her constancy to him, he observes that "woman's words to a love that is eager" are as those written in "wind or water streame." In poem 14 he drops the fictional mask altogether in his direct address to her: "Faire seeke not to be feared, most lovely beloved by thy servants,/For true it is, that they feare many whom many feare." What begins in this group as the lover's attempt to discipline and restrain his desire, ends in frustration and the threat of violence. The first half of Certain Sonnets concludes with a group of three quaterzains, 15, 16a, and 16, which provides three possible responses to the lover's dilemma. In 15, a poem upon an Impresa, the lover contrasts himself to the "seeled" dove to emphasize his frustration. Just as the dove's blindness prevents her from succeeding in a bid for freedom, naivety has rendered the lover totally unprepared for the vicissitudes of love. He has been "cast off" as a lover with neither the strength to live nor courage to die. Now with "wings of fancies," he composes high flown "conceits" whose rewards are small. In 16a, a quaterzain by Edward Dyer, the painful experience of a satyr who kisses the fire brought by Prometheus from heaven is compared to the lover's pain after the heavenly "impression" of his beloved" strikes him. In 16 Sidney responds by expanding the conceit but altering the circumstances in an allegory that reflects the lover's own personal plight. The satyr is frightened by the sound of a horn "which he him selfe did blow," but in the couplet, he musters his spirits by praising Dyer's satyr who "burnt his lips to kisse faire shining fire." In 16, then, at the mid-point of this miscellany of 33 poems, the lover reaffirms his aggressive role towards his beloved. His aggression is directed mostly toward himself, however, for in 17 to 22 he ruthlessly analyzes his sense of alienation and suffering caused by desire. In 17 he claims that his 8 beloved's desire for him is limited and restrained by her deference to the conventions of love. In quaterzain 18, "fancies change" enslaves him with a sense of his own alienation: his mind infects each thing it sees. He desires not to think about his lady in poem 19, so that his "thoughts might have good end," but "reason's strife" are "by senses overthrowne." The "Farewell" of quaterzain 20 and its companion poem, 21, contain the lover's attempt to provide a formal departure from his beloved. In 20, he departs because "the starres with their strange course do binde/ [him] ... to leave," but discovers that absence is as painful as her presence. In 21, he returns to find that his beloved's presence is no better than her absence. The final poems in this group provide what poems 20 and 21 could not, a clear forsaking of his beloved. Against the lady's virtue the lover has tried to force his affections, but to no avail. Now, plagued for his "rash attempt," he describes the death of his physical desire, which, he says, is drowned in her "seas of vertue." Rising to the surface of this sea and then flying upward, his desire, phoenix-like, is transformed into "a purest love" which may move him to a "nobler life." He decides to fashion himself after her virtue: "Now thus this wonder to my selfe I frame." Poems 23 to 30 record the lover's struggle and ultimate rejection of the resolution of 22. While A.C. Hamilton argues that "the farewell to earthly love becomes steadily more explicit" in this final section, I suggest that the lyrics become part of an antiphony of voices defining an experience that can be neither abandoned nor fulfilled.16 The rhetorical technique employed in the final section of the miscellany is one of apophasis in which the poet ironically denies what he says or does by emphasizing especially what he says or does. 17 The first example of this technique is found in his placement of song 23 after the farewell of 22. In this song Sidney provides a catalogue of graces emphasizing the neo-Platonic image of his beloved, but mockingly denies that these qualities are what he sees in her: "But eyes these beauties see not, / Nor sence that grace descryes." She is still to him a woman of the earth, "nature's sweetest light," upon whom he invites us to gaze. That he is not resolved toward the virtuous life is admitted again in song 24 where he considers the enormous effort necessary to turn to virtue. He is adamant in his pursuit of her, so much so that he is willing to seem to change if he thinks 9 success could follow. In the end, however, appearance will belie reality: he will not "change in change, though change change my state." In the narrative verse of poem 25 the lover denies again that he will forsake the life of the senses for her virtue, though he may seem to do so. "Thus do I dye to live thus, / Changed to a change, I change not." Though he admits that the "violence of heav'nly / Beautie" once persuaded him to yield his senses, he has found that this has left him "devoid of all life." In song 26, he claims that her treatment of him has provided insight into the nature of human suffering: "our lives be not immortall, / But to mortall / Fetters tyed." He will not then forsake the sensual life, but attempt to die "in her beams/ Glory trying." Song 27 recalls his affair from the time her "heart enchained" his because of its "sweetness." Now "reason hath thy words removed," and "no more thy beames availe thee." This denial is undermined, however, when he emphasizes that "her chastnesse" has caused his wretchedness, and concludes, "the less I love, I live the less." The placing of two translations from Montemayor's Diana (1559) as the penultimate group in Certain Sonnets suggests that a resolution towards either the fulfillment of desire of the life of virtue is unlikely. Indeed, in Diana, the story of the relationship between Syrenus and Diana remains incomplete, irreconcilable because of misunderstandings between the lovers. Montemayor promises to finish the narrative in the second book, but never succeeds in doing so.18 In poem 28 Sidney also dwells on the unfinished state of the affair. Here the shepherd Sireno laments the changes that have occurred in his beloved since the past: "Who hath such beautie seene / In one that changeth so." He concludes by recalling the translation of Catullus in poem 13, that women's words are "written in sand." In 29 the lover claims that the difference between unfulfilled love and its opposite is the difference between illusion and reality. Sireno holds a mirror to his mistress' face, suggesting that what she sees in the glass is "a shade," but when he gazes into her eyes he is aware of her immediate presence, or what he calls her "true shape." Similarly, he concludes, now that she has "Love's yoke despised," she "sees it but disguised," where he, as "one captiv'd" to love, receives the "lively forme." Now, despite his 10 role as a rejected lover, he has not forsaken love: indeed if anything his constancy in love has brought him closer to understanding its true value. In poem 30 he blames his lady for not enjoying the fullness that love offers them: "Love is not dead, but sleepeth / In her unmatched mind." He concludes by rejecting the "wit" who tries to "temper" love by calling it a "franzie." Critics generally agree that the Petrarchan commiato provides a strong sense of closure to the loose miscellany of poems preceding it. Following Ringler, Hamilton concludes, for example, that the "crucial fact" about the collection is that "love may be rejected." In sonnet 31 the lover "is determined to subdue desire, and in CS 32 he forsakes earthly love." Not until Astrophil and Stella, Hamilton continues, does Sidney "treat a love that may be neither satisfied nor rejected."19 Indeed, at first glance, quaterzain 32 appears fully resolved. The lover forswears secular love and seeks the eternal love of God. Leave me o Love, which reachest but to dust, And thou my mind aspire to higher things: Grow rich in that which never taketh rust: What ever fades, but fading pleasure brings. He bids farewell to love in a manner that "breathes resolution and spiritual integrity." 20 But preceding 32 is quaterzain 31, a poem not about subduing desire but the impossibility of subduing desire. Here the lover sees that regardless of how much he might have enjoyed his lady, desire's "end is never wrought." For vertue hath this better lesson taught, Within my selfe to seeke my onelie hire: Desiring nought but how to kill desire. The violent, paradoxical metaphor in the final statement ironically destroys its initial proposition. If the lover desires to kill desire, he also desires to kill the desire to kill desire, thus admitting his final unwillingness to resolve the conflict between desire and virtue. The rhetorical device used here is an aporia which suggests that the lover has not succeeded in triumphing over his "web of will," but is deadlocked or doubly bound in his commitment to himself and to his lady.21 11 The sudden shift from the "mock resolution" in poem 31 to the unconditional surrender to the "sweet yoke" of "eternal love" in poem 32 forces one to question the final resolution. The term recalls Murray Krieger's point about Renaissance poets who use "mock Metaphors." These metpahors, he suggests, allow us to recognize the voice of the poet-lover but to see the controlling hand of the author which undermines "the completeness of the person's vision, [and] controls it only by allowing it to break apart."22 The effect of the aporia in Certain sonnnets 31 is that we cannot say with confidence that this ending invokes closure, a sense of finality, stability, and integrity in the narrative of the relationship described in the preceding poems.23 The reader is left uncertain whether there is a firm commitment toward "eternal love," or whether the argument has simply advanced one more step in the battle defined in quaterzain 1 between "naked sence" and "reason armed." What is brilliant about 32 is that by itself it is a spiritual tour de force in which the lover announces the commiato, and turns toward the heavenly world. But in the context of the preceding poems the images of the final poem are ambivalent. When the lover refers to one who "seeketh heav'n, and comes of heav'nly breath," the image invokes not only the spiritual world, but the secular world as well. In poem 5, the lover refers to "heaven" in a secular, erotic sense, as the feeling of sensual fulfillment enjoyed by them both. "O my Thoughtes' sweete food, my [my] onely Owner, / O my heaven for Taste, by thy heavenly pleasure." And the expression of desire found in the following miscellany of lyrics describes as much the lover's fantasy towards sexual fulfillment as it does the longing for spiritual transformation. Sidney's interest in the confrontation between sexuality and virtue in Certain Sonnets is supported by two other works written at this time, The Lady of May and Old Arcadia, both of which follow the miscellany in their use of the motif of violence in relationships between male and female characters. In The Lady of May, the "liviler" love of Therion is clearly more pleasurable to his beloved than the unexciting affection of Espilus, but it is finally rejected, in part because "he grows to such rages, that sometimes hie strikes [her], sometimes he rails at her."24 In the Old Arcadia, Musidorus, "overmatiched with the fury of delight," attempts to rape 12 the sleeping Pamela, and Pyrocles "denyes not hee offered vyolence to the Lady Philoclea." 25 By the 1598 folio edition of Sidney's works, the salient references to the violence of sexual desire are eliminated. The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia, containing Sidney's unfinished revisions, had replaced the Old Arcadia, the manuscript of which disappeared until the early twentiethcentury. And poem 5 of Certain Sonnets, the only poem which refers to the consummated sexual relationship, is excluded from the folio. From the preceding analysis, however, one can argue that Sidney used the openendedness of the miscellany to textualize the paradox of human desire: the poet-lover is seen at once longing for the fulfillment of sexual consummation while at the same time he is drawn to the possibility of spiritual renewal. When the collection is framed with the innamoramento and the commiato, a conventional Petrarchan closure is provided. But this closure is deferred as the paradox of the lover's desire in the intervening lyric voices challenges the resolution in the final poem. Sidney's choice of the miscellany is entirely clear at this point in his poetic career. There were no structural or rhetorical limitations to the genre, and regardless of his poetic experiments, any form of lyric could be accommodated. He recognized an opportunity to experiment with a dozen and a half lyric sub-genres in which he could record the disparate voices of a poet-lover obsessed by desire. His poetic virtuosity transforms the structure of the gentleman's miscellany into a genre with remarkable rhetorical force. He turns to the sonnet sequence because he recognizes the structural and thematic potential of the sonnet form. In Astrophil and Stella he continues to represent the lover's plight in a narrative which elaborates what was initiated in Certain Sonnets: the ambivalence of human longing. 13 Endnotes Germaine Warkentin describes the Penshurst library in "Sidney's Authors" in Sir Philip Sidney's Achievement, M.J.B. Allen, Dominic Baker-Smith, Arthur F. Kinney eds. (New York: AMS Press, 1990) 89. She traces the intertextual links in "The Meeting of the Muses: Sidney and the Mid-Tudor Poets" in Gary Waller, Michael D. Moore, eds. Sir Philip Sidney and the Interpretation of Renaissance Culture: The Poet in His Time and in Ours (London: Croom Helm, 1984) 17-33. 1 Sir Philip Sidney, A Defence of Poetry, J.A. Van Dorsten ed. (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1966) 2324. 2 The Short Title Catalogue records eight editions of Tottel's miscellany alone in this period. Other miscellanies include Barnabe Googe's Eglogs, Epytaphes, and Sonettes (1563), Clement Robinson's A Handful of Pleasant Delights (1566), Thomas Howell's Arbour of Amitie or Pleasant Poems (1567), John Symon's A Plesant Posie, or Sweete Nosegay of Fragrant Smelling Flowers 1572, George Gascoigne's A Hundreth Sundrie Flowres Bounde up in One Small Poesie (1573), The Posies of George Gascoigne (1575), Isabella Whitney's A Sweet Nosegay, or Pleasant Posy (1573), Robert Edwards's, The Paradise of Daintie Devices (1576), Thomas Proctor's A Gorgeous Gallery of Gallant Inventions (1578), C.H.'s The Forest of Fancy (1579), Edmund Spenser's The Shepheardes Calender (1579), Humphrey Gillford's A Posie of Gilloflowers, (1580). 3 Richard C. Newton, "Making Books from Leaves: Poets Become Editors" in Print and Culture in the Renaissance: Essays on the Advent of Printing in Europe. Gerald P. Tyson, Sylvia S. Wagonheim eds. (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1986) 247. 4 Remarkably, the pioneer works of both Arthur Case and Elizabeth Pomeroy overlook the single-author miscellany. The former defines the miscellany as "a book of verse by three or more authors," excluding song-books and hymn-books, in A Bibliography of English Poetical Miscellanies 1521-1750 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1935) v. The latter accepts this definition in her study of the development and the conventions of the genre, in The Elizabethan Miscellanies: Their Development and Conventions (Berkeley: University of California, 1973) 1. 5 Germaine Warkentin, "Sidney's Certain Sonnets: Speculations on the Evolution of the Text" in Library 2 (1980) 432. 6 William A. Ringler Jr. ed. The Poems of Sir Philip Sidney, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962) 423-426. 7 See Victor Skretkowicz's observations that "the extent of the revisions of the 1590 text of the Old Arcadia "were clearly indicated by the author through his deletion, interpolation, and annotations." Cited in Margaret Hannay biography's of the Countess of Pembroke. Hannay concludes that the Countess and Greville shared Sidney's final revision for the Old Arcadia in which the lust of Pyrochles and Musidorus is displaced in the actions of Amphialus in the Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia (1593) which became the copy text for the folio edition. Sidney's Phoenix: Mary Sidney, Dutchess of Pembroke (New York: Oxford UP, 1990) 75. 8 14 William A. Ringler Jr. "The Text of The Poems of Sidney: Twenty-five Years After" (133) in Allen, M.J.B., Baker-Smith, Cominic, Kinney Arthur F., Sullivan, Margaret eds. Sir Philip Sidney's Achievements (New York: AMS; 1990) 129-144. 9 Germaine Warkentin, "`Love's sweetest part, variety': Petrarch and the Curious Frame of the Renaissance Sonnet Sequence." Renaissance and Reformation ii (1975): 18. 10 Sir Philip Sidney, A Defence of Poetry, Jan Van Dorsten ed. (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1966) 25, 27. 11 A broader context for the deconstructive impulse in laguagage in language is provided by Jacques Derrida, "Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences" (278-294) in Writing and Difference, trans. Alan Bass (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1978). 12 A.C. Hamilton, Sir Philip Sidney: A Study of His Life and Works (London: Cambridge UP, 1977) 72. 13 14 Warkentin, "The Meeting of the Muses" 26. 15 Christopher Martin, "Sidney and the Limits of Eros" Spenser Studies VII (1987): 240-243. 16 Hamilton Sir Philip Sidney 77. For an interesting discussion of this rhetorical device, see Frank Kermode, "Endings, Continued" in Languages of the Unsayable: The Play of Negativity in Literature and Literary Theory, Sanford Budick and Wolfgang Iser eds. (New York: Columbia UP, 1989) 71-94. 17 Judith M. Kennedy, ed., Diana of George of Montemayor, trans. Bartholomew Yonge 1583 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1968) 242. For a precise summary of Sidney's dept to Montemayor, see Kinney, Humanist Poetics: Thought, Rhetoric, and Fiction in Sixteenth Century England (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts, 1986) 247-251. 18 19 Hamilton Sir Philip Sidney 78-79. 20 J.S. Lever, The Elizabethan Love Sonnet (1966. London: Metheun, 1978) 82. George Puttenham defines this rhetorical figure as "the doubtfull, [so] called ... because oftentimes we will seeme to cast perils and make doubt of things when by a plaine speech wee might affirme or deny him." See George Puttenham, The Arte of English Poesie (1589), Gladys Doidge Willcock and Alice Walker, eds. (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1936) III 234. 21 Murray Krieger, "The Figure in the Renaissance Poem as Bound and Unbounded" in A Reopening of Closure: Organicism Against Itself (New York: Columbia UP, 1989) 9-10. 22 Barbara Herrnstein Smith, Poetic Closure (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1968) viii. 23 15 Katherine Duncan-Jones and Jan Van Dorsten eds., Miscellaneous Prose of Sir Philip Sidney (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1972) 8. 24 Jean Robertson, ed. Sir Philip Sidney: The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia (The Old Arcadia) Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973. 25