Moby Dick Plot Overview: Summary & Key Events

advertisement

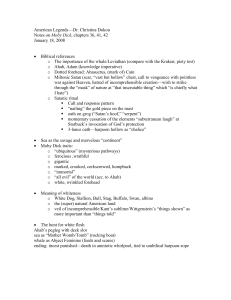

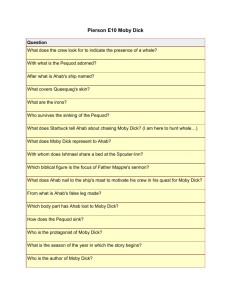

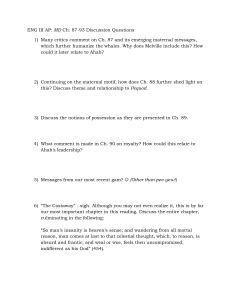

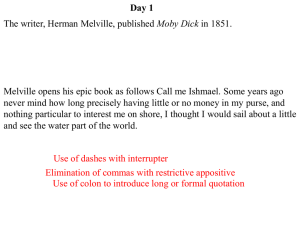

Plot Overview http://www.gradesaver.com/classicnotes/titles/moby/shortsumm.html The novel Moby Dick by Herman Melville is an epic tale of the voyage of the whaling ship the Pequod and its captain, Ahab, who relentlessly pursues the great Sperm Whale (the title character) during a journey around the world. The narrator of the novel is Ishmael, a sailor on the Pequod who undertakes the journey out of his affection for the sea. Moby Dick begins with Ishmael's arrival in New Bedford as he travels toward Nantucket. He rests at the Spouter Inn in New Bedford, where he meets Queequeg, a harpooner from New Zealand who will also sail on the Pequod. Although Queequeg appears dangerous, he and Ishmael must share a bed together and the narrator quickly grows fond of the somewhat uncivilized harpooner. Queequeg is actually the son of a High Chief who left New Zealand because of his desire to learn among Christians. The next day, Ishmael attends a church service and listens to a sermon by Father Mapple, a renowned preacher who delivers a sermon considering Jonah and the whale that concludes that the tale is a lesson to preacher Truth in the face of Falsehood. On a schooner to Nantucket, Ishmael and Queequeg come across a local bumpkin who mocks Queequeg. However, when this bumpkin is swept overboard, Queequeg saves him. In Nantucket, Queequeg and Ishmael choose between three ships for a year journey, and decide upon the Pequod. The Captain of the Pequod, Peleg, is now retired, and merely owns the boat with another Quaker, Bildad. Peleg tells them of the new captain, Ahab, and immediately describes him as a grand and ungodly man. Before leaving for their voyage, Ishmael and Queequeg come across a stranger named Elijah who predicts disaster on their journey. Before leaving on the Pequod, Elijah again predicts disaster. Ishmael and Queequeg board the Pequod, where Captain Ahab is still unseen, secluded in his own cabin. Peleg and Bildad consult with Starbuck, the first mate. He is a Quaker and a Nantucket native who is quite practical. The second mate is Stubb, a Cape Cod native with a more jovial and carefree attitude. The third is Flask, a Martha's Vineyard native with a pugnacious attitude. Melville introduces the rest of the crew, including the Indian harpooner Tashtego, the African harpooner Daggoo. Several days into the voyage, Ahab finally appears as a man seemingly made of bronze who stands on an ivory leg fashioned from whalebone. He eventually gets into a violent argument with Stubb when the second mate makes a joke at Ahab's expense, and kicks him. This leads Stubb to dream of kicking Ahab's ivory leg off, but Flask claims that the kick from Ahab is a sign of honor. At last, Ahab tells the crew of the Pequod to look for a white-headed whale with a wrinkled brow: Moby Dick, the legendary whale that took Ahab's leg. Starbuck tells Ahab that his obsession with Moby Dick is madness, but Ahab claims that all things are masks and there is some unknown reasoning behind that mask that man must strike through. For Ahab, Moby Dick is that mask. Ahab himself seems to recognize his own madness. Starbuck begins to worry that the ship is overmatched by the mad captain and knows that he will see an impious end to Ahab. While Queequeg and Ishmael weave a sword-mat for lashing to their boat, the Pequod soon comes upon a whale and Ahab orders his crew to their boats. Ahab orders his special crew, which Ishmael compares to "phantoms," to their boats. The crew attacks a whale and Queequeg does strike it, but this is insufficient to kill it. Among the "phantoms" in the boat is Fedallah, a sinister Parsee. After passing the Cape of Good Hope, the Pequod comes across the Goney (Albatross), another ship on its voyage. Ahab asks whether they have seen Moby Dick as the ships pass one another, but Ahab cannot hear his answer. The mere passing of the ships is unorthodox behavior, for ships will generally have a 'gam,' a meeting between two ships. The Pequod does have a gam with the next ship it encounters, the Town-Ho. Ishmael interrupts his narration to tell a story that was told to him by the crew of the Town-Ho, just as he would tell it to a circle of Spanish friends after his journey on the Pequod. The story concerns the near mutiny on the Town-Ho and its eventual conflict with Moby Dick. The Pequod does vanquish the next whale that it comes across, as Stubb strikes a whale with his harpoon. However, as the crew of the Pequod attempts to bring the whale into the ship, sharks attack the carcass and Queequeg nearly loses his hand while fending them off. The Pequod next comes upon the Jeroboam, a Nantucket ship afflicted with an epidemic. Stubb later tells a story about the Jeroboam and a mutiny that occurred on this ship because of a Shaker prophet, Gabriel, on board. The captain of the Jeroboam, Mayhew, warns Ahab about Moby Dick. After vanquishing a Sperm Whale, Stubb next also kills a Right Whale. Although this is not on the ship's agenda, the Pequod pursues a Right Whale because of the good omens associated with having the head of a Sperm Whale and a head of a Right Whale on a ship. Stubb and Flask discuss rumors that Ahab has sold his soul to Fedallah. The next ship that the Pequod meets is the Jungfrau (Virgin), a German ship in desperate need of oil. The Pequod competes with the Virgin for a large whale, and the Pequod is successful in defeating it. However, the whale carcass begins to sink as the Pequod attempts to secure it and thus the Pequod must abandon it. The Pequod next finds a large group of Sperm Whales and injures several of them, but only captures a single one. Stubb concocts a plan to swindle the next ship that the Pequod meets, the French ship Bouton-deRose (Rosebud), of ambergris. Stubb tells them that the whales that they have vanquished are useless and could damage their ship, and when the Rosebud leaves these behind the Pequod takes them in order to gain the ambergris in one of them. Several days after encountering the Rosebud, a young black man on the boat, Pippin, becomes frightened while lowering after a whale and jumps from the boat, becoming entangled in the whale line. Stubb chastises him for his cowardice and tells him that he will be left at sea if he jumps again. When Pippin (Pip) does the same thing again, Stubb remains true to his word and Pip only survives because a nearby boat saves him. Nevertheless, Pip loses his sanity from the event. The next ship that the Pequod encounters, a British ship called the Samuel Enderby, bears news of Moby Dick but its crewman Dr. Bunger warns Ahab to leave the whale alone. Later, Ahab's leg breaks and the carpenter must fix it. Ahab behaves scornfully toward the carpenter. When Starbuck learns that the casks have sprung a leak, he goes to Ahab's cabin to report the news. Ahab disagrees with Starbuck's advice on the matter, and becomes so enraged that he pulls a musket on Starbuck. Although Ahab warns Starbuck that there is but one God on Earth and one Captain on the Pequod, Starbuck tells him that he will be no danger to Ahab, for Ahab is sufficient danger to himself. Ahab does relent to Starbuck's advice. Queequeg becomes ill from fever and seems to approach death, so he asks for a canoe to serve as a coffin. The carpenter measures Queequeg for his coffin and builds it, but Queequeg returns to health, claiming that he willed his own recovery. Queequeg keeps the coffin and uses it as a sea chest. Upon reaching the Pacific Ocean, Ahab asks Perth the blacksmith to forge a harpoon to use against Moby Dick. Perth fashions a harpoon that Ahab demands be tempered with the blood of his pagan harpooners, and he howls out that he baptizes the harpoon in the name of the devil. The next ship that the Pequod meets is the Bachelor, a Nantucket ship whose captain denies the existence of Moby Dick. The next day, the Pequod slays four whales, and that night Ahab dreams of hearses. He and Fedallah pledge to slay Moby Dick and survive the conflict, and Ahab boasts of his own immortality. Ahab must soon decide between an easy route past the Cape of Good Hope back to Nantucket and a difficult route in pursuit of Moby Dick. Ahab easily chooses to continue his quest. The Pequod soon comes upon a typhoon on its journey in the Pacific, and while battling this storm the Pequod's compass moves out of alignment. When Starbuck learns this and goes to Ahab's cabin to tell him, he finds the old man asleep. Starbuck considers shooting Ahab with his musket, but he cannot move himself to shoot his captain after he hears Ahab cry in his sleep "Moby Dick, I clutch thy heart at last." The next morning after the typhoon, Ahab corrects the problem with the compass despite the skepticism of his crew and the ship continues on its journey. Ahab learns that Pip has gone insane and offers his cabin to the poor boy. The Pequod comes upon yet another ship, the Rachel, whose captain, Gardiner, knows Ahab. He requests the Pequod's help in searching for Gardiner's son, who may be lost at sea, but Ahab flatly refuses when he learns that Moby Dick is nearby. The final ship that the Pequod meets is the Delight, a ship that has recently come upon Moby Dick and has nearly been destroyed by its encounter with the whale. Before finally finding Moby Dick, Ahab reminisces about the day nearly forty years before in which he struck his first whale, and laments the solitude of his years out on the sea. He admits that he has chased his prey as more of a demon than a man. The struggle against Moby Dick lasts three days. On the first day, Ahab spies the whale himself, and the whaling boats row after it. Moby Dick attacks Ahab's boat, causing it to sink, but Ahab survives the ordeal when he reaches Stubb's boat. Despite this first failed attempt at defeating the whale, Ahab pursues him for a second day. On the second day of the chase, roughly the same defeat occurs. This time Moby Dick breaks Ahab's ivory leg, while Fedallah dies when he becomes entangled in the harpoon line and is drowned. After this second attack, Starbuck chastises Ahab, telling him that his pursuit is impious and blasphemous. Ahab declares that the chase against Moby Dick is immutably decreed, and pursues it for a third day. On the third day of the attack against Moby Dick, Starbuck panics for ceding to Ahab's demands, while Ahab tells Starbuck that "some ships sail from their ports and ever afterwards are missing," seemingly admitting the futility of his mission. When Ahab and his crew reach Moby Dick, Ahab finally stabs the whale with his harpoon but the whale again tips Ahab's boat. However, the whale rams the Pequod and causes it to begin sinking. In a seemingly suicidal act, Ahab throws his harpoon at Moby Dick but becomes entangled in the line and goes down with it. Only Ishmael survives this attack, for he was fortunate to be on a whaling boat instead of on the Pequod. Eventually he is rescued by the Rachel as its captain continues his search for his missing son, only to find a different orphan. Character List Ishmael - The narrator, and a junior member of the crew of the Pequod. Ishmael doesn’t play a major role in the events of the novel, but much of the narrative is taken up by his eloquent, verbose, and extravagant discourse on whales and whaling. Ahab - The egomaniacal captain of the Pequod. Ahab lost his leg to Moby Dick. He is singleminded in his pursuit of the whale, using a mixture of charisma and terror to persuade his crew to join him. As a captain, he is dictatorial but not unfair. At moments he shows a compassionate side, caring for the insane Pip and musing on his wife and child back in Nantucket. Moby Dick - The great white sperm whale. Moby Dick, also referred to as the White Whale, is an infamous and dangerous threat to seamen, considered by Ahab the incarnation of evil and a fated nemesis. Starbuck - The first mate of the Pequod. Starbuck questions Ahab’s judgment, first in private and later in public. He is a religious man who believes that Christianity offers a way to interpret the world around him, although he is not dogmatic or pushy about his beliefs. Starbuck acts as a conservative force against Ahab’s mania. Queequeg - Starbuck’s skilled harpooner and Ishmael’s best friend. Queequeg was once a prince from a South Sea island who stowed away on a whaling ship in search of adventure. He is a composite of elements of African, Polynesian, Islamic, Christian, and Native American cultures. He is brave and generous, and enables Ishmael to see that race has no bearing on a man’s character. Stubb - The second mate of the Pequod. Stubb, chiefly characterized by his mischievous good humor, is easygoing and popular. He proves a bit of a nihilist, always trusting in fate and refusing to assign too much significance to anything. Tashtego - Stubb’s harpooner, Tashtego is a Gay Head Indian from Martha’s Vineyard, one of the last of a tribe about to disappear. Tashtego performs many of the skilled tasks aboard the ship, such as tapping the case of spermaceti in the whale’s head. Like Queequeg, Tashtego embodies certain characteristics of the “noble savage” and is meant to defy racial stereotypes. He is, however, more practical and less intellectual than Queequeg: like many a common sailor, Tashtego craves rum. Flask - A native of Tisbury on Martha’s Vineyard and the third mate of the Pequod. Short and stocky, Flask has a confrontational attitude and no reverence for anything. His stature has earned him the nickname “King-Post,” because he resembles a certain type of short, square timber. Daggoo - Flask’s harpooner. Daggoo is a physically enormous, imperious- looking African. Like Queequeg, he stowed away on a whaling ship that stopped near his home. Daggoo is less prominent in the narrative than either Queequeg or Tashtego. Pip - A young black boy who fills the role of a cabin boy or jester on the Pequod. Pip has a minimal role in the beginning of the narrative but becomes important when he goes insane after being left to drift alone in the sea for some time. Like the fools in Shakespeare’s plays, he is half idiot and half prophet, often perceiving things that others don’t. Fedallah - A strange, “oriental” old Parsee (Persian fire-worshipper) whom Ahab has brought on board unbeknownst to most of the crew. Fedallah has a very striking appearance: around his head is a turban made from his own hair, and he wears a black Chinese jacket and pants. He is an almost supernaturally skilled hunter and also serves as a prophet to Ahab. Fedallah keeps his distance from the rest of the crew, who for their part view him with unease. Peleg - A well-to-do retired whaleman of Nantucket and a Quaker. As one of the principal owners of the Pequod, Peleg, along with Captain Bildad, takes care of hiring the crew. When the two are negotiating wages for Ishmael and Queequeg, Peleg plays the generous one, although his salary offer is not terribly impressive. Bildad - Another well-to-do Quaker ex-whaleman from Nantucket who owns a large share of the Pequod. Bildad is (or pretends to be) crustier than Peleg in negotiations over wages. Both men display a business sense and a bloodthirstiness unusual for Quakers, who are normally pacifists. Father Mapple - A former whaleman and now the preacher in the New Bedford Whaleman’s Chapel. Father Mapple delivers a sermon on Jonah and the whale in which he uses the Bible to address the whalemen’s lives. Learned but also experienced, he is an example of someone whose trials have led him toward God rather than bitterness or revenge. Captain Boomer - The jovial captain of the English whaling ship the Samuel Enderby. Boomer lost his arm in an accident involving Moby Dick. Unlike Ahab, Boomer is glad to have escaped with his life, and he sees further pursuit of the whale as madness. He is a foil for Ahab, as the two men react in different ways to a similar experience. Gabriel - A sailor aboard the Jeroboam. Part of a Shaker sect, Gabriel has prophesied that Moby Dick is the incarnation of the Shaker god and that any attempts to harm him will result in disaster. His prophecies have been borne out by the death of the Jeroboam’s mate in a whale hunt and the plague that rages aboard the ship. Analysis of Major Characters Ishmael Despite his centrality to the story, Ishmael doesn’t reveal much about himself to the reader. We know that he has gone to sea out of some deep spiritual malaise and that shipping aboard a whaler is his version of committing suicide—he believes that men aboard a whaling ship are lost to the world. It is apparent from Ishmael’s frequent digressions on a wide range of subjects—from art, geology, and anatomy to legal codes and literature—that he is intelligent and well educated, yet he claims that a whaling ship has been “[his] Yale College and [his] Harvard.” He seems to be a selftaught Renaissance man, good at everything but committed to nothing. Given the mythic, romantic aspects of Moby-Dick, it is perhaps fitting that its narrator should be an enigma: not everything in a story so dependent on fate and the seemingly supernatural needs to make perfect sense. Additionally, Ishmael represents the fundamental contradiction between the story of MobyDick and its setting. Melville has created a profound and philosophically complicated tale and set it in a world of largely uneducated working-class men; Ishmael, thus, seems less a real character than an instrument of the author. No one else aboard the Pequod possesses the proper combination of intellect and experience to tell this story. Indeed, at times even Ishmael fails Melville’s purposes, and he disappears from the story for long stretches, replaced by dramatic dialogues and soliloquies from Ahab and other characters. Ahab Ahab, the Pequod’s obsessed captain, represents both an ancient and a quintessentially modern type of hero. Like the heroes of Greek or Shakespearean tragedy, Ahab suffers from a single fatal flaw, one he shares with such legendary characters as Oedipus and Faust. His tremendous overconfidence, or hubris, leads him to defy common sense and believe that, like a god, he can enact his will and remain immune to the forces of nature. He considers Moby Dick the embodiment of evil in the world, and he pursues the White Whale monomaniacally because he believes it his inescapable fate to destroy this evil. According to the critic M. H. Abrams, such a tragic hero “moves us to pity because, since he is not an evil man, his misfortune is greater than he deserves; but he moves us also to fear, because we recognize similar possibilities of error in our own lesser and fallible selves.” Unlike the heroes of older tragic works, however, Ahab suffers from a fatal flaw that is not necessarily inborn but instead stems from damage, in his case both psychological and physical, inflicted by life in a harsh world. He is as much a victim as he is an aggressor, and the symbolic opposition that he constructs between himself and Moby Dick propels him toward what he considers a destined end. Moby Dick In a sense, Moby Dick is not a character, as the reader has no access to the White Whale’s thoughts, feelings, or intentions. Instead, Moby Dick is an impersonal force, one that many critics have interpreted as an allegorical representation of God, an inscrutable and all-powerful being that humankind can neither understand nor defy. Moby Dick thwarts free will and cannot be defeated, only accommodated or avoided. Ishmael tries a plethora of approaches to describe whales in general, but none proves adequate. Indeed, as Ishmael points out, the majority of a whale is hidden from view at all times. In this way, a whale mirrors its environment. Like the whale, only the surface of the ocean is available for human observation and interpretation, while its depths conceal unknown and unknowable truths. Furthermore, even when Ishmael does get his hands on a “whole” whale, he is unable to determine which part—the skeleton, the head, the skin—offers the best understanding of the whole living, breathing creature; he cannot localize the essence of the whale. This conundrum can be read as a metaphor for the human relationship with the Christian God (or any other god, for that matter): God is unknowable and cannot be pinned down. Themes, Motifs & Symbols (Themes are the fundamental and often universal ideas explored in a literary work.) The Limits of Knowledge As Ishmael tries, in the opening pages of Moby-Dick, to offer a simple collection of literary excerpts mentioning whales, he discovers that, throughout history, the whale has taken on an incredible multiplicity of meanings. Over the course of the novel, he makes use of nearly every discipline known to man in his attempts to understand the essential nature of the whale. Each of these systems of knowledge, however, including art, taxonomy, and phrenology, fails to give an adequate account. The multiplicity of approaches that Ishmael takes, coupled with his compulsive need to assert his authority as a narrator and the frequent references to the limits of observation (men cannot see the depths of the ocean, for example), suggest that human knowledge is always limited and insufficient. When it comes to Moby Dick himself, this limitation takes on allegorical significance. The ways of Moby Dick, like those of the Christian God, are unknowable to man, and thus trying to interpret them, as Ahab does, is inevitably futile and often fatal. The Deceptiveness of Fate In addition to highlighting many portentous or foreshadowing events, Ishmael’s narrative contains many references to fate, creating the impression that the Pequod’s doom is inevitable. Many of the sailors believe in prophecies, and some even claim the ability to foretell the future. A number of things suggest, however, that characters are actually deluding themselves when they think that they see the work of fate and that fate either doesn’t exist or is one of the many forces about which human beings can have no distinct knowledge. Ahab, for example, clearly exploits the sailors’ belief in fate to manipulate them into thinking that the quest for Moby Dick is their common destiny. Moreover, the prophesies of Fedallah and others seem to be undercut in Chapter 99, when various individuals interpret the doubloon in different ways, demonstrating that humans project what they want to see when they try to interpret signs and portents. The Exploitative Nature of Whaling At first glance, the Pequod seems like an island of equality and fellowship in the midst of a racist, hierarchically structured world. The ship’s crew includes men from all corners of the globe and all races who seem to get along harmoniously. Ishmael is initially uneasy upon meeting Queequeg, but he quickly realizes that it is better to have a “sober cannibal than a drunken Christian” for a shipmate. Additionally, the conditions of work aboard the Pequod promote a certain kind of egalitarianism, since men are promoted and paid according to their skill. However, the work of whaling parallels the other exploitative activities—buffalo hunting, gold mining, unfair trade with indigenous peoples—that characterize American and European territorial expansion. Each of the Pequod’s mates, who are white, is entirely dependent on a nonwhite harpooner, and nonwhites perform most of the dirty or dangerous jobs aboard the ship. Flask actually stands on Daggoo, his African harpooner, in order to beat the other mates to a prize whale. Ahab is depicted as walking over the black youth Pip, who listens to Ahab’s pacing from below deck, and is thus reminded that his value as a slave is less than the value of a whale. Motifs (Motifs are recurring structures, contrasts, or literary devices that can help to develop and inform the text’s major themes.) Whiteness Whiteness, to Ishmael, is horrible because it represents the unnatural and threatening: albinos, creatures that live in extreme and inhospitable environments, waves breaking against rocks. These examples reverse the traditional association of whiteness with purity. Whiteness conveys both a lack of meaning and an unreadable excess of meaning that confounds individuals. Moby Dick is the pinnacle of whiteness, and Melville’s characters cannot objectively understand the White Whale. Ahab, for instance, believes that Moby Dick represents evil, while Ishmael fails in his attempts to determine scientifically the whale’s fundamental nature. Surfaces and Depths Ishmael frequently bemoans the impossibility of examining anything in its entirety, noting that only the surfaces of objects and environments are available to the human observer. On a live whale, for example, only the outer layer presents itself; on a dead whale, it is impossible to determine what constitutes the whale’s skin, or which part—skeleton, blubber, head—offers the best understanding of the entire animal. Moreover, as the whale swims, it hides much of its body underwater, away from the human gaze, and no one knows where it goes or what it does. The sea itself is the greatest frustration in this regard: its depths are mysterious and inaccessible to Ishmael. This motif represents the larger problem of the limitations of human knowledge. Humankind is not all-seeing; we can only observe, and thus only acquire knowledge about, that fraction of entities— both individuals and environments—to which we have access: surfaces. Symbols (Symbols are objects, characters, figures, or colors used to represent abstract ideas or concepts.) The Pequod Named after a Native American tribe in Massachusetts that did not long survive the arrival of white men and thus memorializing an extinction, the Pequod is a symbol of doom. It is painted a gloomy black and covered in whale teeth and bones, literally bristling with the mementos of violent death. It is, in fact, marked for death. Adorned like a primitive coffin, the Pequod becomes one. Moby Dick Moby Dick possesses various symbolic meanings for various individuals. To the Pequod’s crew, the legendary White Whale is a concept onto which they can displace their anxieties about their dangerous and often very frightening jobs. Because they have no delusions about Moby Dick acting malevolently toward men or literally embodying evil, tales about the whale allow them to confront their fear, manage it, and continue to function. Ahab, on the other hand, believes that Moby Dick is a manifestation of all that is wrong with the world, and he feels that it is his destiny to eradicate this symbolic evil. Moby Dick also bears out interpretations not tied down to specific characters. In its inscrutable silence and mysterious habits, for example, the White Whale can be read as an allegorical representation of an unknowable God. As a profitable commodity, it fits into the scheme of white economic expansion and exploitation in the nineteenth century. As a part of the natural world, it represents the destruction of the environment by such hubristic expansion. Queequeg’s Coffin Queequeg’s coffin alternately symbolizes life and death. Queequeg has it built when he is seriously ill, but when he recovers, it becomes a chest to hold his belongings and an emblem of his will to live. He perpetuates the knowledge tattooed on his body by carving it onto the coffin’s lid. The coffin further comes to symbolize life, in a morbid way, when it replaces the Pequod’s life buoy. When the Pequod sinks, the coffin becomes Ishmael’s buoy, saving not only his life but the life of the narrative that he will pass on. Themes (from other sources) http://www.gradesaver.com/classicnotes/titles/moby/themes.html Ahab as a Blasphemous Figure: A major assumption that runs through Moby Dick is that Ahab's quest against the great whale is a blasphemous activity, even apart from the consequences that it has upon its crew. This blasphemy takes two major forms: the first type of blasphemy to prevail within Ahab is hubris, the idea that Ahab thinks himself the equal of God. The second type of blasphemy is a rejection of God altogether for an alliance with the devil. Melville makes this point explicit during various episodes of the novel, such as the instance in which Gabriel warns Ahab to "think of the blasphemer's end" (Chapter 71: The Jeroboam's Story) and the appraisal of Ahab from Peleg in which he designates him as an ungodly man (Chapter 16: The Ship). The idea that Ahab's quest for Moby Dick is an act of defiance toward God assuming that Ahab is omnipotent first occurs before Ahab is even introduced during Father Mapple's sermon. The lesson of the sermon, which concerns the story of Jonah and the whale, is to warn against the blasphemous idea that a ship can carry a man into regions where God does not reign. Ahab parallels this idea when he compares himself to God as the lord over the Pequod (Chapter 109: Ahab and Starbuck in the Cabin). Melville furthers this idea through the prophetic dream that Fedallah tells Ahab that causes Ahab to conclude that he is immortal. Nevertheless, a more disturbing type of blasphemy also emerges during the course of the novel in which Ahab does not merely believe himself omnipotent, but aligns himself with the devil during his quest. Ahab remains in collaboration with Fedallah, a character rumored by Stubb to be the devil himself, and when Ahab receives his harpoon he asks that it be baptized in the name of the devil, not in the name of the father. The Whale as a Symbol of Unparalleled Greatness: When Melville, through Ishmael, describes the Sperm Whale during the many non-narrative chapters of Moby Dick, the idea that the whale has no parallel in excellence recurs as a nearly labored point. Melville approaches this theme from a variety of standpoints, whether biological or historical, in order to prove the superiority of the whale over all other creatures. During a number of occasions Melville relates whaling to royal activity, as when he notes the strong devotion of Louis XVI to the whaling industry and considers the whale as a delicacy fit for only the most civilized. In additional, Melville cites the Indian legends of Vishnoo, the god who became incarnate in a whale. Even when discussing the whale in mere aesthetic terms Melville lauds it for its features, devoting an entire chapter (42) to the whiteness of the whale, while degrading those artists who falsely depict the whale. The theme of the excellence of the whale serves to place Ahab's quest against Moby Dick as, at best, a virtually insurmountable task in which he is doomed to failure. Melville constructs the whale as a figure that cannot be easily vanquished, if it can be defeated at all. The Whale as an Undefinable Figure: While Melville uses the whale as a symbol of excellence, he also resists any literal interpretation of that excellence by refusing to equate the species with any concrete object or idea. For Melville, the whale is an indefinite figure, as best shown in "The Whiteness of the Whale" (Chapter 42). Melville defines the whiteness as absence of color and thus finds the whale as having an absence of meaning. Melville bolsters this premise that the whale cannot be defined through the various stories that Ishmael tells in which scholars, historians and artists misinterpret the whale in their respective fields. Indeed, the extended discussion of the various aspects of the whale also serve this purpose; by detailing the various aspects of the whale in their many forms, Melville makes the whale an even more inscrutable figure whose essence cannot be described through its history or physiognomy. The recurring failed attempts to find a concrete definition of the whale leave the Sperm Whale, and Moby Dick more specifically, as abstract and devoid of any concrete meaning. By allowing the whale to exist as a mysterious figure, Melville does not pin the whale down as an easy metaphorical parallel, but instead leaves a multiplicity of various interpretations for Moby Dick. A more personalized interpretation for the thematic significance of the inability to define the whale relates to Ahab's comparison of Moby Dick to a mask that obscures the unknown reasoning that he seeks. In this interpretation, the inability to define a whale is significant not in itself, but because it stands in the way of greater reasoning and understanding. Moby Dick as a Part of Ahab: Throughout the novel, Melville creates a relationship between Ahab and Moby Dick despite the latter's absence until the final three chapters through the recurrence of elements creating a close relationship between Ahab and the whale. The most significant of these is the actual physical presence of the Sperm Whale as part of Ahab's body in the form of Ahab's ivory leg. The whale is a physical part of Ahab in this instance; it is literally a part of Ahab. Melville also develops this theme through the uncanny sense that Ahab has for the whale. Ahab has a nearly psychic sense of Moby Dick's presence, and more tragically, the idea of Moby Dick perpetually haunts the formidable captain. This theme serves in part to better explain the depth of emotion behind Ahab's quest for the whale; as a living presence that haunts Ahab's life, he feels that he must continue on his quest no matter the cost. The Contrast between Civilized and Pagan Society: The relationship between Queequeg and Ishmael throughout Moby Dick generally illustrates the prevalent contrast between civilized, specifically Christian societies and uncivilized, pagan societies. The continued comparisons and contrasts between these two types of societies is often favorable for Melville, particularly in the discussion of Queequeg, the most idealized character in the novel, whose uncivilized and imposing appearance only obscures his actual honor and civilized demeanor. In this respect, Melville is fit simply to deconstruct Queequeg and place him in entirely sympathetic terms, finding the characters from civilized and from uncivilized societies to be virtually identical. Nevertheless, Melville does not include these thematic elements simply for a lesson on other cultures; a recurring theme equates non-Christian societies with diabolical behavior, particularly when in reference to Ahab. Ahab specifically chooses the three pagan characters' blood when he wishes to temper his harpoon in the name of the devil, while the most obviously corrupt character in Moby Dick is conspicuously the Persian Fedallah, whom the other characters believe to be Satan in disguise. With the exception of Queequeg, equating the pagan characters with Satan does align with the general religious overtones of the novel, one which presumes Christianity as its basis and moral ground. The Sea as a Place of Transition: In Moby Dick, the sea represents a transitional place between two distinct states. Melville shows this early on in the case of Queequeg and the other Isolatoes (Daggoo and Tashtego), who represents the transition from uncivilized to civilized society unbound by any specific nationality, but in an overwhelming amount of cases this transitional theme relates to the precarious line between life and death. There are a number of characters who teeter at the brink between life and death, whether literally or metaphorically, throughout Moby Dick. Queequeg again proves to be an example: during his illness he prepares for death and in fact remains in his own coffin waiting for illness to overtake him, but it never does (Chapter 110: Queequeg in his coffin). The coffin itself becomes a transitional element several chapters later when the carpenter converts it into a life-buoy and it thus comes to symbolize both the saving of a life and the end of one (Chapter 126: The LifeBuoy). Several of the minor characters in Moby Dick also exist in highly transitional states between life and death. After Pippin jumps to his death from the whaling boat and is saved only by chance, he loses his sanity and behaves as if a part of him, the "infinite of his soul" had already died; essentially, the character becomes a shell of a person waiting for death. Melville further elaborates this theme through the blacksmith, who works on the sea primarily as a means to escape life. He came on his journey to escape from the trappings of life after his family had died, and exists on sea primarily as a passage before his eventual death. Harbingers and Superstition: A recurring theme throughout Moby Dick is the appearance of harbingers, superstitious and prophecies that foreshadow a tragic end to the story. Even before Ishmael boards the Pequod, the Nantucket strangers Elijah warns Ishmael and Queequeg against traveling with Captain Ahab. The Parsee Fedallah also has a prophetic dream concerning Ahab's quest against Moby Dick, dreaming of hearses (although he misinterprets the dream to mean that Ahab will certainly kill Moby Dick). Indeed, the characters are bound by superstition and myth: the only reason that the Pequod kills a Right Whale is the legend that a ship will have good luck if it has the head of a Right Whale and the head of a Sperm Whale on its opposing sides. An additional harbinger of doom found in Moby Dick occurs when a hawk takes Ahab's hat, thus recalling the story of Tarquin and how his wife Tanaquil predicted that it was a sign that he would become king of Rome. The purpose of these omens throughout Moby Dick is to create a sense of inevitability. Even from the beginning of the journey the Pequod's mission is doomed by Captain Ahab, and the invocation of various omens serves to endow this mission with a sense of grandeur and destiny. It is no suicide mission that Ahab undertakes, but a grand folly of hubris. THEMES ANALYSIS http://www.pinkmonkey.com/booknotes/monkeynotes/pmMobyDick71.asp Herman’s Melville’s Moby Dick is by far his best literary work as it is not just another sea adventure. In the story, the author has a message for his readers. But he suggests his message through a fascinating array of symbols and imagery. The moral message comes across through the biblical story of Jonah and the whale. In the biblical story (Old Testament) Jonah does not heed the word of God and consequently, he has to face God’s wrath and go on a ship to Tarshish where he is stopped by a terrible storm at sea. Finally when the crewmembers find out that it is because of the sinner Jonah that this storm had been engineered he is thrown into the sea. Realizing his mistake, Jonah prays for forgiveness. The result is that God forgives Jonah and asks the whale to release him. The story as part of the Chaplain’s Sunday Sermon gives the reader an inkling of the events to occur later in the book, namely the journey on the Pequod and its tragic end. Just as in the story, Jonah strays away from the path of God, so does the evil Captain Ahab in his single mindedness try to avenge the whale, Moby Dick. But while Jonah repents for his sins and is forgiven, Ahab does not pay heed to the warning signal given out by the terrible storm that damages the Pequod’s sails. And he dies while trying to strike a harpoon into Moby Dick. The author deliberately makes a veiled reference to the novel’s message, for it is something that goes against the tenets of Christian philosophy that says that "man’s life is but a shadow on earth." Though man suffers on earth he attains heavenly bliss after death. But Melville does not agree with this and instead states through symbolism and the journey of the Pequod that there is only one life., and man pays for his deeds during his lifetime and not after death. This view seems to agree with the religious revivalism in the 1830s, which spoke of instant or immediate salvation. Though the book has a lot of depth and symbols for the reader to unearth, the one striking theme which appears again and again is about man’s struggle against the forces of nature. It is evident in Captain Ahab in his pursuit of Moby Dick. It is also evident in all the crewmembers as they strive to conquer the hardships both physical and psychological that are faced on their journey to the Pacific. The author definitely sees something positive in this struggle. For mankind has progressed through its struggle against and conquest of its physical environment. Just as Ahab brings about his and his ship’s destruction in his mad pursuit of Moby Dick, today we are destroying the delicate balance of the earth by trying to gain mastery over it, and we all are aware where it will lead us - a major ecological disaster. In the context of man and the environment, time and again in the story, the author uses various symbols of the sea to give his views on man’s life vis-a-vis the vast, complex universe around him. Through various symbols of the whale and the oceans, the author reflects on man’s position, his role in the Universe as well as his lack of understanding the complex world he is living in. Rather than seeing the world in black and white, one must see it in shades of gray as Ishmael does. Melville uses the world of the whale to reveal this theme. Using the whale as an example, the writer makes profound observations such as how whale’s eyes are placed on both sides of his head so he can see more than one object. However, while the whale can see several aspects in life, man can see one and understand only one because both of his eyes see ahead of him only. Moby Dick: A critique of the whaling industry. The whaling industry in the U.S. during the 1900s was both an essential as well as a profitable industry. Its products such as the sperm oil, made from the upper layer (just below the skin of the whale) of fat in the sperm whale was used to light lamps in the nineteenth century. In the book, Melville provides a lot of factual information on the types of whales, their size and anatomy. Besides, he also informs us of the size of the industry - which employed 18,000 men and 700 vessels and the profits that this industry brought to the country - $20,000,000 per annum. Yet, the whaling profession is considered to be a lowly one and was scorned by people in general. In other words, the book reflects the ideas that 19th century society in America held: that the whaling profession had ‘no dignity’. The author counters all these ideas in the book. But while he extols the whaling industry, he also reveals its darker side. Although there were lots of profits and adventure, there was also high risk involved. For sailors have lost their lives in innumerable accidents that occur on the sea. Further, he also makes several suggestions that could improve working conditions of the sailors especially the harpooner--in reducing the chances of accidents on the boats. In doing so, the author not only reveals his expertise on the subject of whaling, but also his skill in putting difficult and technical subjects in a simple and interesting manner. After reading the novel, the reader is left with nothing less than awe and admiration for ordinary courage and strength in whalemen and their struggle against the vast and perilous seas. Melville gives a new dignity to the labor and sweat of the whaling ships. Thus, Moby Dickis a vivid descriptive commentary on blood, sweat and hard physical labor that went into the profit-making whaling industry that it was in 19th century America. Essays The Attack on Transcendentalism by Keegan Lerch Herman Melville, the author of Moby Dick, attacks the views of the Transcendentalists by portraying Moby Dick, the white whale, as the personification of evil. This completely opposes the Transcendentalist idea that there is only good in the world. Throughout the story, Melville also incorporates the Anti-Transcendental principles that the truths of existence are illusive and that nature is indifferent, unforgiving, and often unexplainable. Moby Dick and Captain Ahab both refute the Transcendentalist principle that there is no evil, there is only love. The Transcendentalists feel that the world is filled with goodness, however, the Anti-Transcendentalists believe in the more reasonable idea that man has the potential to be either good or bad. Moby Dick is portrayed as evil in the story as Ahab tells of how he lost his leg to the white behemoth. After Ahab loses his leg to the white whale he Creates himself as the "racehero"; moving against the presence of evil, Ahab vows to kill the source of evil: Moby Dick. (Stern, 74) Ahab, therefore, unconscientiously casts his own evil onto Moby Dick. The whale also personifies the evil that exisists within Ahab. The evil Ahab possesses is the result of his obsession with extinguishing the evil in the whale. The very evil that exists in Ahab is that which the transcendentalists deem to be non-existent. Melville is therefore striking heavily upon the ideals of the Transcendentalists. Ahab also seeks to control nature, which goes against Transcendentalist views that man and nature are equal before God. Ahab's passion to dominate nature gives him an evil persona and counters Transcendentalist views. "He, Ahab, is evil, Melville seems to say, because he seeks to overthrow the established order of dualistic human creationÖ" (Stern, 74) Nature's indifference is shown by Moby Dick as it pays sparse attention to Ahab, regardless of how much time Ahab puts into the whale. "the great white whale that is essentially indifferent to him." (Stern) According to Transcendentalist views, nature is supposed to be good and loving, but this is disproved by Melville's blatantly obvious portrayals of the malicious sides of Nature. The Transcendentalist principle that nature is good and rational is tackled by the AntiTranscendentalist ideal that nature is indifferent, unforgiving, and often unexplainable. Melville presents this in Moby Dick by using the sea as a setting. The sea is a vast and often times unexplainable phenomenon. The damage that the whale does to the boats and crew members is how Melville shows the true nature of the sea. "But as the oarsmen violently forced their boat through the sledge-hammering seas, the before whale-smitten bow-ends of two planks burst through, and in an instant almost, the temporarily disabled boat lay nearly level with the waves" (Melville, 327) The story, Moby Dick attacks the rosy-cheeked ideals of the Transcendentalists by introducing the characteristics of evil and indifference. The Transcendentalists believe that there is no evil, however, it is shown in Moby Dick that Man has the potential for good and evil, as does nature. In Anti-Transcendentalism nature is not portrayed as a wonderful, rational thing, but realistically as an indifferent, unforgiving, and unexplainable wonder. Melville deals heavy blows against the optimistic views of the Transcendentalists by portraying characteristics of evil and attacking nature. Melville weaves Anti-Transcendentalist principles by using images of destruction and iniquity. These images show the true nature of the world and do not attempt to hide it in an attempt to make the world seem happy. SYMBOLISM / MOTIFS Moby Dick is not just another book based on the writer’s own experiences at sea. It is a deeply symbolic story of the conflicting forces of good and evil. The symbols used in the book are linked to the sea, sailors and the thriving whaling industry of the nineteenth century. The author, through the use of rather mundane images and events related to life at sea, reflects on life, the universe, morality and death. For instance, the ocean in the novel represents the world or life where man struggles and plays his role. Thus the Pequod with sailors from varied nationalities and alien lands, is a microcosm of the world we are living in. Through the physical features of the whale, the author makes profound observations on life and man’s position vis-a-vis the complex universe. To cite an example, in the chapter where the narrator pauses to talk about the whale’s skeleton and how one cannot figure out where the skull (of the whale) ends and the tailbone begins. This relates to however hard one may strive, it is not possible for one to understand the complex universe. The author’s deep philosophical statements through common sights and events at sea reveal his skill as a writer as well as his understanding of the subjects he is discussing. In Melville’s novel, almost all the characters are just as important as the events and situations that are depicted. Therefore through the sensitive portrayal of Queequeg, the aborigine from New Zealand who becomes a close friend of Ishmael, the author comments on the so-called ‘civilized’ Christian world as opposed to the world of the savage. Moreover, the bond that formed between Ishmael and Queequeg is significant for through them, the author seems to suggests that in the uncertain and difficult world, a trusted and loving friend can help human beings. Also, the friendship between Ishmael and Queequeg suggests that a bond can be formed between people cutting across national boundaries and cultures. Finally, through the elusive white whale Moby Dick, the author suggests that there is a supreme spirit controlling our world and destinies. So just as in the biblical story of Jonah and the whale, in the book also, the white whale is used to punish the evil in the world manifested in Ahab. Moby Dick also represents something that is unconquerable by man, suggesting that man cannot control or destroy everything. There are some things that are beyond human control. Thus, in the novel, each event, name or character reveals some aspect of life, morality, or human nature. Just as Ishmael reflects over these images and symbols, the reader too is caught in the spell of the fascinating array of symbols and reflects upon the subjects they represent.