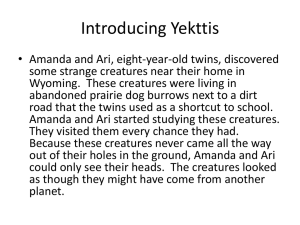

Chapter 4 - Cadair Home

advertisement