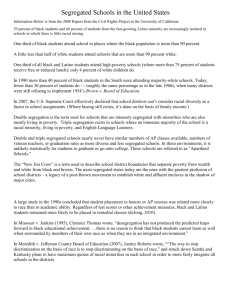

Edit of Justice Breyer`s Dissent

advertisement