Taitel.doc

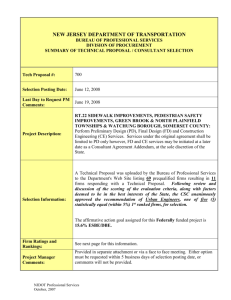

advertisement