Much of the play takes place in a psychological construct

advertisement

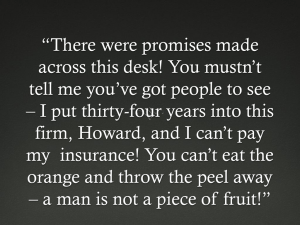

Source Citation:Ardolino, Frank. "'I'm not a dime a dozen! I am Willy Loman!': the significance of names and numbers in Death of a Salesman." Journal of Evolutionary Psychology (August 2002): 174(11). Expanded Academic ASAP. Gale. UDLibSEARCH - Main Account. 15 Feb. 2008 <http://find.galegroup.com/itx/start.do?prodId=EAIM>. Gale Document Number:A90682854 Much of the play takes place in a psychological construct which Willy creates. An Eden-like paradise which lies at the center of his neurosis, it is characterized by the paradoxical union of reality and his delusory fulfillment of his grandiose dreams of omnipotence. Willy's paradise, which he identifies with the time in which Biff and Happy were growing up in Brooklyn, was also synonymous with his and his sons' exclusive society in which they expressed, reflected, and validated his belief in their virtual divinity. Expressing his enthusiasm for Biff's divine condition, Willy ironically incorporated the concept of progress, time's movement, into his changeless paradise. He believed that Biff, who was already "divine" as a football player, would become more so as a businessman. Before Biff realized Willy's projected future, however, he lost faith in Willy's dreams, left the state of mind or paradise Willy had created, and destroyed its coherence. As a result, Willy moved from the condition of stasis to one created by a confusion of the present and of its fragmented paradise. Willy never experiences the future which is part of normal chronological time because he recognizes only the future which he believes is latent in his paradise. To his destruction, he seeks to actualize it. Willy Loman reconstructs the past "not chronologically as in flashback, but dynamically with the inner logic of his erupting volcanic unconscious" (Schneider 252.) This "visualized psychoanalytic interpretation woven into reality" (Schneider 253) serves as Miller's principal dramatic method--the simultaneous existence of the past and present in Willy's disordered mind. Miller has said that he was obsessed with "a mode that would open a man's head for a play to take place inside it, evolving through concurrent rather than consecutive actions," which "turned him [Willy] to see present through-past and past through present, a form that ... would be ... a collecting point for all that his ... society had poured into him" (Timebends 129, 131). But this narrative poem is an expressionistic nightmare. The repetition of the names and numbers produce an echo chamber of mockery indicative of Willy's failure to achieve his dreams. He is like a rat in a maze; no matter where he turns he runs into the same indices of defeat. This is a deterministic universe, one that parallels the world of Greek tragedy. Willy can not escape the fate which he in a sense has created through the demented dreams instilled in him by his perversion of the American dream of success (Messenger 199). Miller suggests that the power of the psyche is comparable to the fate represented by the omnipotent and capricious gods of Greek tragedy. For no apparent reason, Willy's psyche blinds him to the madness of his grandiose dreams of omnipotence and compels him to attempt to replace reality with his own concept of it. (2) In other terms, it drives him to challenge the gods. His delusory fulfillment of his grandiose dreams and the punishment for his hubris come together in his act of suicide. Happy, who is obsessed by sexuality, is a base variation of Willy and a mocking comment on his insane aspirations and death. Characterized by duality and duplicity, Happy lives in unending alternations of assertion and contradiction which result in nothingness. In contrast, Biff's psyche or fate mercifully releases him from Willy's dreams and their effects into the ordered multiplicity and movement of normal life. Biff's good fortune, however, does not explain or justify Willy's tragedy and Happy's meaninglessness. In the face face of the incomprehensible and uncontrollable power of the psyche, modern audiences are moved to pity and terror as ancient audiences were moved by the fall of these heroes in Greek tragedy But in reality, name imagery reveals Willy and Biff's failures. Willy has been working on commission "like a beginner, an unknown" (57). After he overhears Biff tell Linda and Happy that businessmen have laughed at him for years (61), he pathetically asserts his importance by using names: "They laugh at me, heh? Go to Filene's, go to the Hub, go to Slattery's, Boston. Call out the name Willy Loman and see what happens! Big Shot!" (162). Name imagery further points to Biff's failure to develop a career. When he attempted to meet with Bill Oliver, a businessman, he waited in his reception room, and "[k]ept sending my name in" (104), but it meant nothing to Oliver, and his door remained closed. In sum, when announcing a name, ringing a bell, and opening a door constitute the dramatic action, these actions contrast Willy's belief in his omnipotence with his base reality. Upon Biff's arrival at Willy's hotel, he asks the telephone operator to ring his room to announce his arrival; when Biff opens the door to Willy's room, he discovers Willy's adultery. The names that appear throughout Death of a Salesman can be grouped into three related categories: geographical, personal, and business, the most significant of which often begin with "B," "F," and "S." The geographical names consist primarily of the places Willy travels to as a salesman; the personal include his family, friends, and business associates. Finally, the business category is comprised of the names of the people, stores, and products Willy reveres and intones throughout the play as proof of his value and the signs of the success he envisions for his sons. But years after Biff became disillusioned with Willy, he uses imagery of vain inflation to blame Willy for his failure to achieve a career:" ... I never got anywhere because you [Willy] blew me so full of hot air I could never stand taking orders from anybody!" (131). And he accuses Happy of being a liar: "You big blow, are you the assistant buyer? You're one of the two assistants to the assistant, aren't you" (131). The group of three which Biff describes forms a deflated parallel to the one Willy once imagined would create a sensation upon entering the Boston stores--Biff and Happy accompanying him, carrying his sample bags. In the light of the Lomans' lack of success, the bags, suggestive of wind-bags, allude to the burden of Willy's meretricious beliefs and unfounded grandiosity that Biff and Happy bore. The image of inflated emotion and explosion inherent in Bangor is cruelly echoed in the word blow, which can mean "to treat" as well as "a violent impact," and in the name of the restaurant "Frank's Chop House." The name Frank recalls Frank Wagner, Willy's former benevolent boss, and chop, which refers to a cut of meat, also means "a sharp blow." In anticipation of getting a loan to establish a sporting goods business, Biff asks Linda to invite Willy to a celebration at Frank's chop house. "Biff came to me this morning, Willy, and he said, `Tell Dad, we want to blow him to a big meal.' Be there [at Frank's Chop House] at six o'clock, you and your two boys are going to have dinner" (74). At the restaurant, Biff, who has stolen Bill Oliver's pen and escaped from his office in disgrace, tries to make Willy face the reality of their respective failures. Deeply angered, Willy strikes Biff, a blow which precipitates his subsequent hallucination in which Biff knocks on--or strikes--the door of Willy's hotel room in Boston, initiating the series of events that resulted in Biff's disillusionment. Willy measures people's worth by their "names"--their popularity and reputation--and by the money they earn and amass. He cherishes and intones sacred names like Dave Singleman, Ben Loman, Bill Oliver, and Frank Wagner, among others, who "represent aspects of his splintered mind" (Hoeveler 632). Names beginning with "B" are used to present taunting images of success and failure. Ben, Willy's successful brother, walked into the jungle at seventeen and emerged at twenty-one a wealthy man. Bill Oliver, Biff's past employer and present delusory hope, has a first name which alludes to his monetary success, but he does not lend the money to Biff for his hopeless athletic scheme. Moreover, by its closeness to Biff and its equation with Willy, Bill mocks their respective failure. Similarly, Willy's reference to B.F. Goodrich, the founder and namesake of a tire manufacturing company, as a businessman who succeeded later in life also ironically alludes to Biff (18). The initials, "B.F.," sound like "Biff," and the last name describes the financial condition that Willy wants for him. In addition, Bernard, Charley's son, has achieved the success that Willy predicted he would never have because he was not well-linked, unlike Biff who was the popular football hero destined for fame and fortune. Willy Loman, the lowman on the economic totem pole, is tormented by the success of Ben, Bernard, and Bill Oliver and by the failure of Biff, which began with his son's flunking math seventeen years ago. When Biff went to Boston to ask Willy to talk to his math teacher Birnbaum about raising his grade, he saw Willy with The Woman and lost faith in Willy and himself. As Harshbarger has noted, the first syllable in "Birnbaum" is reminiscent of fire and and the second one means "tree" in German (58). The whole name echoes Willy's cry of disaster, "the woods are burning" (41,107). Willy uses the phrase to signify his growing sense of dread, just before he tells Biff and Happy that he was fired. In the context of the events at the Boston hotel, Birnbaum's name is a double pun. Willy who knows that Biff is knocking on the door of his room, refuses to open it, but The Woman insists: "Maybe the hotel's on fire!" (116). Her exclamation echoes Willy's locution and alludes to imminent disaster for him--Biff's recognition of his duplicity. The next important letter is "F," found primarily in the names of people, usually Frank or a derivative, Which convey a conflict between benevolence and protection on the one hand, and dismissal and degradation on the other. The principal benevolent Frank is Frank Wagner, Willy's former employer, who in 1928, according to Willy, made promises to him which his son Howard, whom Willy says he helped name(97), has failed to honor. Other benevolent characters named Frank are Biff's teenaged friend who, under Biff's direction, helps with household chores (34), and the repairman Frank, whom Willy depends upon to repair the cherished Chevrolet (36). At the opposite pole is Miss Francis, Willy's Boston mistress. Finally, there is Frank's Chop House where Willy relives the Boston episode and Happy ignores his father's distress to leave with Miss Forsythe, the "chippy" who parallels Miss Francis. Two's or doubles are an important Indication of Willy's inescapable malaise. The play has two acts and takes two days, and Willy lives a dual existence in the past and the present. Willy carries two suitcases (12), emblematic of his business world and the burden of his two sons, who are two years apart (19) and are paralleled by Howard's two children, who are also two years apart (77), and Bernard's two sons (92). Willy mentions the two elm trees which used to be in the backyard but were chopped down, a symbol of destruction of his idyllic plans for his sons (17). There are two sets of brothers, Ben and Willy, and Happy and Biff. Further, Willy gives two pairs of silk stockings to Miss Francis, who is paralleled by the two "chippies" the boys pick up at Frank's where Willy expects to celebrate a dual triumph. He feels sure that Howard will give him the non-traveling job that he wants and that Biff will get the loan from Oliver. When Biff orders drinks that evening, "Scotch all around. Make it doubles," and Stanley, the waiter repeats "doubles," they unwittingly echo the dual failures of Willy and Biff. Despite his liberating insight, Biff is not able to get Willy to see reality at Frank's Chop House, where a scene of filial denial is enacted which parallels the episode in Boston when Willy denied Biff and Linda in his pursuit of Miss Francis. In a parody of his father's career and values, Happy woos the "strudel" (100) by pretending to be a champagne salesman and by claiming that Biff plays quarterback for the New York Giants, an ironic expansion of Willy's past adulation of him as a stellar high-school quarterback playing the championship game at Ebbets Field. Happy also asserts that his real name is Harold (six letters), which recalls Howard Wagner (six letters each), another son who is disloyal to his father and dismissive of another father. Happy "sells himself" to Miss Forsythe by ordering the champagne just as Willy "scored" with Miss Francis by giving her Linda's silk stockings. Happy denies his father--"that's not my father. He's just a guy" (115)--to go with Miss Forsythe and Letta, names that respectively represent Willy's lack of foresight and his defeat as exemplifies by ominous repetitions. After his sons leave, Willy ends up hallucinating in the downstairs toilet, which signals his descent into the depths of his madness as he relives the events in Boston when Miss Francis emerged from Willy's bathroom and was seen by Biff. He is helped by the waiter Stanley, whose name recalls the Standish Arms, and he leaves, completely despondent, to search for the fruitless seeds, the image of his faithless sons who have never taken hold in the soil of his own prelapsarian backyard garden, in the hardware store on 6th Avenue, the street of the dead (122). Miller uses the repeated names, letters, and numbers not only to impart a sense of concrete and specific realism to the dreamlike scenes but also to create an expressionistic juxtaposition of the past and present and desire and guilt in Willy's disordered mind. Everyone can empathize with the tragedy of a little man who persists in trying to gain the elusive success that is all wrong for him and his sons. Willy's dilemma is universal, and Miller's depiction of it is both simple and complex, realistic and surrealistic, and ultimately, sad and nightmarishly fatalistic.