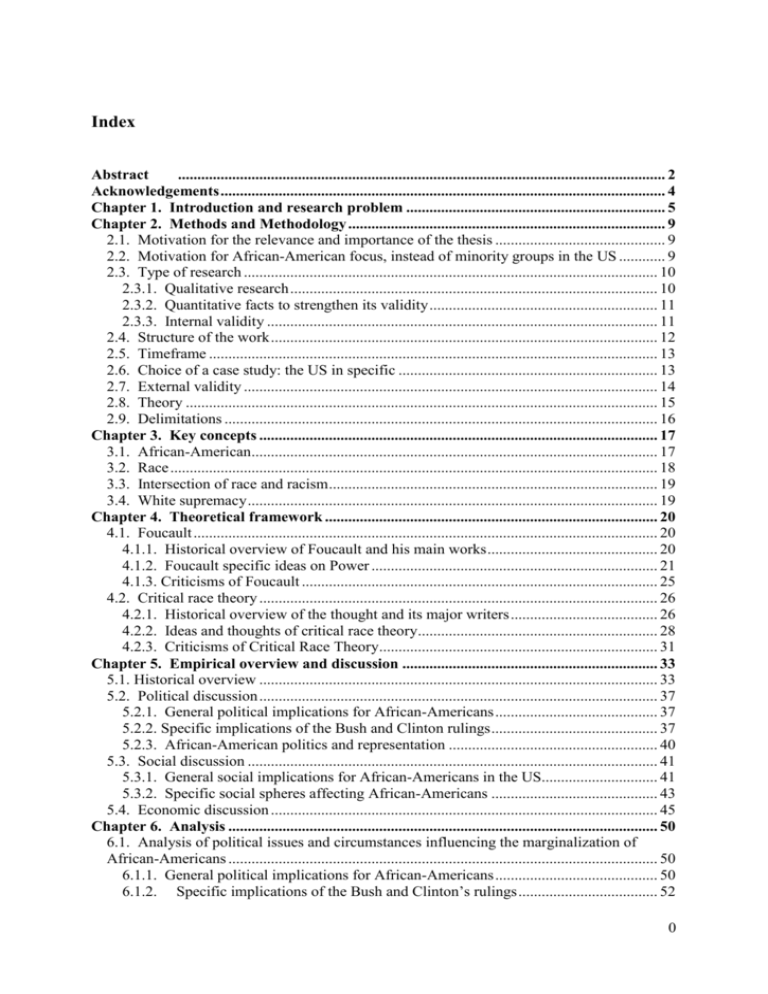

Final thesis

advertisement